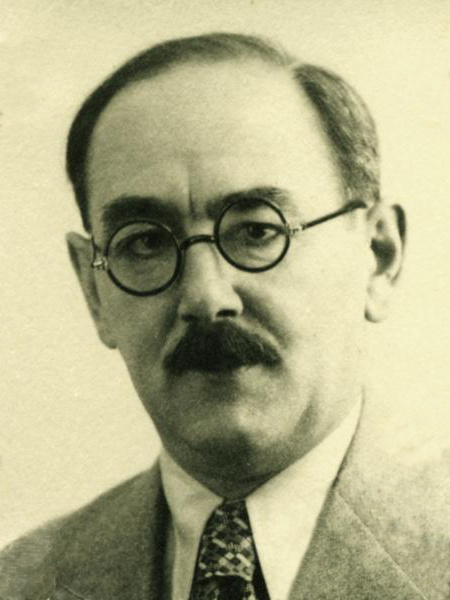

Matyas Rakosi was, from 1949 to 1953, Joseph Stalin’s man in Hungary. A Stalinist to his core, Rakosi secured and maintained power by methods of terror and oppression, but, soon after the death of his mentor, was removed from office.

Matyas Rakosi was born one of eleven children to Jewish parents on 9 March 1892 in a village called Ada, now in Serbia but then part of the Austrian-Hungary empire. He would later renounce his Judaism and all forms of religion. A polyglot, Rakosi could speak eight languages. He served in the Austrian-Hungarian army during the First World War, being taken prisoner on the Eastern Front by the Russians and held for years in a prisoner of war camp during which time he converted to communism. Returning home in 1918 as a member of the Hungarian Communist Party, he was given command of the Red Guard during the 134-day Hungarian Soviet Republic formed by Bela Kun in 1919. Following the collapse of the republic, Rakosi fled to Austria, then onto Moscow.

Matyas Rakosi was born one of eleven children to Jewish parents on 9 March 1892 in a village called Ada, now in Serbia but then part of the Austrian-Hungary empire. He would later renounce his Judaism and all forms of religion. A polyglot, Rakosi could speak eight languages. He served in the Austrian-Hungarian army during the First World War, being taken prisoner on the Eastern Front by the Russians and held for years in a prisoner of war camp during which time he converted to communism. Returning home in 1918 as a member of the Hungarian Communist Party, he was given command of the Red Guard during the 134-day Hungarian Soviet Republic formed by Bela Kun in 1919. Following the collapse of the republic, Rakosi fled to Austria, then onto Moscow.

Prisoner

In 1924, Stalin sent Rakosi back to Hungary with instructions to re-establish the Hungarian Communist Party which had been forced underground by the new regime. Rakosi was arrested in 1927, and sentenced to eight years imprisonment, which, later, was extended to life. But in November 1940, after 13 years in a Hungarian prison, he was released – in exchange for a set of symbolic Hungarian flags and banners that had been stored in a Moscow museum since their capture in 1849. Again, Rakosi returned to Moscow to prepare for the next stage in the communist struggle for power in his homeland.

When, in April 1945, at the end of the Second World War, Stalin’s Red Army liberated Hungary from Nazi control, Rakosi again returned to Hungary and served as General Secretary for the Hungarian communists.

Slices of salami

In the first post-war Hungarian elections in November 1945, the communists won only 17 per cent of the vote, losing heavily to the Independent Smallholders’ Party. But with Soviet advice at hand, mainly in the form of veteran Politburo member, Kliment Voroshilov, Rakosi and the communists bullied their way into positions of power. But still, they fared little better in a second election, thus the communists forced other leading parties to merge with them and arrested every potential opponent of the party. And thereby Rakosi gained power, later boasting that he had cut up his opponents one-by-one like ‘slices of salami’. By 1949, Hungary had officially become the People’s Republic of Hungary with Rákosi at its helm.

Under Matyas Rakosi’s rule of terror, some 2,000 Hungarians were executed and up to 100,000 imprisoned by the newly-formed state security, or secret police, the AVO. Most notoriously, he had the popular Cardinal Mindszenty (pictured) arrested, tortured, tried and imprisoned. But while Rakosi may have been effective in the murderous business of politics, he had no talent for running the country. His policies of collectivization, modelled on that of the Soviet Union’s, failed miserably, causing economic ruin and widespread famine. But while Stalin remained alive, Rakosi’s position was secure.

Under Matyas Rakosi’s rule of terror, some 2,000 Hungarians were executed and up to 100,000 imprisoned by the newly-formed state security, or secret police, the AVO. Most notoriously, he had the popular Cardinal Mindszenty (pictured) arrested, tortured, tried and imprisoned. But while Rakosi may have been effective in the murderous business of politics, he had no talent for running the country. His policies of collectivization, modelled on that of the Soviet Union’s, failed miserably, causing economic ruin and widespread famine. But while Stalin remained alive, Rakosi’s position was secure.

Death of Stalin

But on 5 March 1953, Stalin died. In July, within four months of Stalin’s death, Rakosi was replaced by the reformist and populist, Imre Nagy. But Nagy became too popular for the Kremlin’s liking and in April 1955 Rakosi was put back in charge and the terror and oppression started anew.

A year later, in June 1956, Rakosi was replaced by fellow hardline Stalinist, Erno Gero. The Kremlin, finally realising how unpopular Rakosi was, told him to resign on grounds of ill health and fly to Moscow for treatment. He did, never to return to his home country. He was not missed.

Exile

Nagy (pictured) was temporarily re-instated as leader during the ill-fated Hungarian Revolution of October / November 1956. Following the collapse of the revolution and the re-establishment of communist control, Rakosi was not invited back. Instead he remained in Moscow, politically exiled. In 1962, Matyas Rakosi suffered the ultimate indignity when he was expelled from the Hungarian Communist Party, the organisation he’d spent his life working for. He died 5 February 1971, aged 78.

Nagy (pictured) was temporarily re-instated as leader during the ill-fated Hungarian Revolution of October / November 1956. Following the collapse of the revolution and the re-establishment of communist control, Rakosi was not invited back. Instead he remained in Moscow, politically exiled. In 1962, Matyas Rakosi suffered the ultimate indignity when he was expelled from the Hungarian Communist Party, the organisation he’d spent his life working for. He died 5 February 1971, aged 78.

Rupert Colley

Read more about the Hungarian Revolution in The Hungarian Revolution, 1956 (126 pages) available as ebook and paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, Apple Books and other stores.

Read more about the Hungarian Revolution in The Hungarian Revolution, 1956 (126 pages) available as ebook and paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, Apple Books and other stores.