The ghost of Dunkirk has been a constant presence in Britain’s consciousness ever since the events that played out in this French coastal town in the spring of 1940. It scarred us but it has also provided a benchmark for endurance and stoicism, the ‘Dunkirk spirit’. But it’s easy to forget what exactly happened on that French beach. Now, 77 years on, we have Christopher Nolan’s latest film, Dunkirk.

The ghost of Dunkirk has been a constant presence in Britain’s consciousness ever since the events that played out in this French coastal town in the spring of 1940. It scarred us but it has also provided a benchmark for endurance and stoicism, the ‘Dunkirk spirit’. But it’s easy to forget what exactly happened on that French beach. Now, 77 years on, we have Christopher Nolan’s latest film, Dunkirk.

The tension kicks off within the first minute. It then doesn’t let go until the last. But before we get to the film, a quick paragraph of history…

Dunkirk – the background

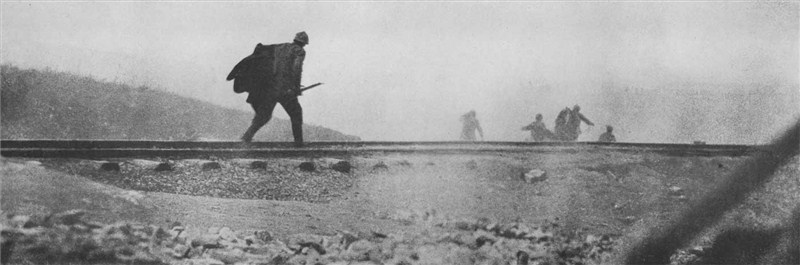

On 10 May 1940, German forces launched their attack against France. Their advance was spectacular. By the end of the month, over a third of a million Allied troops were trapped in the French coastal town of Dunkirk, subject to German shells and attacks from the air. It was only a matter of days before the full-blown assault would come. Losses were heavy but by 4 June, the evacuation had brought back to Britain 338,226 British, French and other Allied soldiers. Plus 170 dogs. Soldiers put much store by their mascots.

A triptych

Dunkirk is a very visceral experience. You experience the fear and the vulnerability of the men stranded with little more than their rifles. Usually, whenever we have a film based on a huge event, for example, Titanic, there has to be a romantic subplot in there somewhere. Not so with Dunkirk, and it’s all the better for it. It’s also a very British experience. Although we catch a brief glimpse of a few French and colonial troops, we do not see a single German. The German is the unseen enemy, unseen but still too close for comfort. And when he does appear, hurling in his Messerschmitt towards our brave boys on the beach or on a vessel, the sound is frightening. It’s a film with surprisingly little dialogue. It’s also a war film with surprisingly little blood – there are no close-ups of limbs being ripped off, of men being blown to smithereens or in their death throes. Nolan was certainly chasing the lower age certificate here. Yet he manages to achieve this without diminishing his stranglehold on us.

On 22 June 1940, Hitler, now the German Führer, got his revenge – it was the turn of the French to surrender, and Hitler made sure that it was done in the most demeaning circumstances possible – in exactly the same carriage and in the same spot as the signing twenty-two years earlier.

On 22 June 1940, Hitler, now the German Führer, got his revenge – it was the turn of the French to surrender, and Hitler made sure that it was done in the most demeaning circumstances possible – in exactly the same carriage and in the same spot as the signing twenty-two years earlier. Here, below, is a brief resume

Here, below, is a brief resume

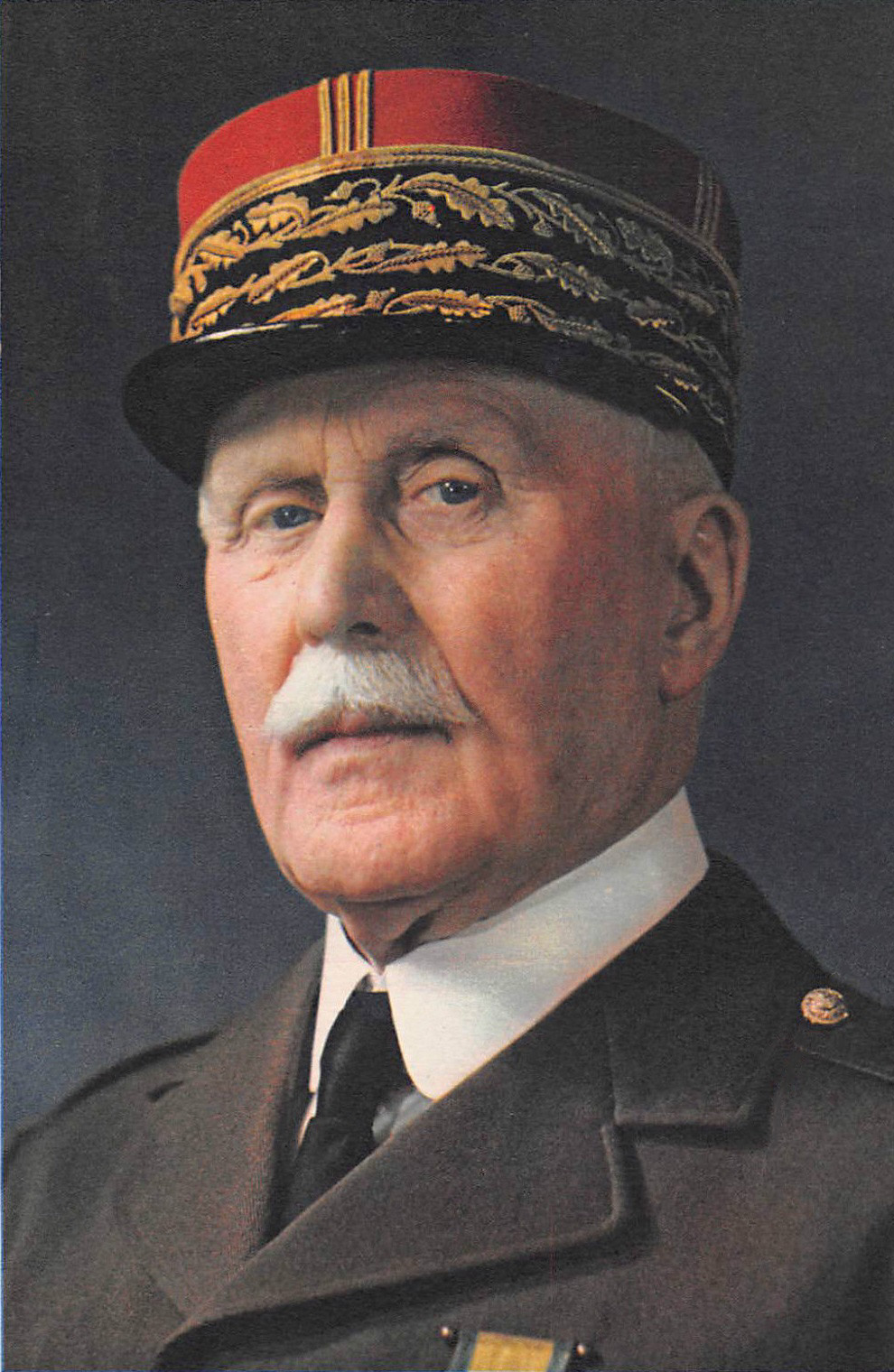

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’.

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’.