In November 1914, the Ottoman Empire, entered the war on the side of the Central Powers and on Christmas Day went on the offensive against the Russians, launching an attack through the Caucasus. Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II sent an appeal to Britain, asking for a diversionary attack that would ease the pressure on Russia. From this came the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign.

Naval Assault

The British planned its diversionary attack, to use the Royal Navy to take control of the Dardanelles Straits from where they could attack Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. By capturing Constantinople, the British hoped then to link up with their Russian allies. The attack would, it hoped, have the additional benefit of drawing German troops away from both the Western and Eastern Fronts.

The Dardanelles, a strait of water separating mainland Turkey and the Gallipoli peninsula, is sixty miles long and, at its widest, only 3.5 miles. Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, insisted that the Royal Navy, acting alone, could succeed. On 19 February, a flotilla of British and French ships pounded the outer forts of the Dardanelles and a month later attempted to penetrate the strait. It failed, losing six ships (three sunk and three damaged), two-thirds of its fleet. Soldiers, it was decided, would be needed after all.

ANZACs

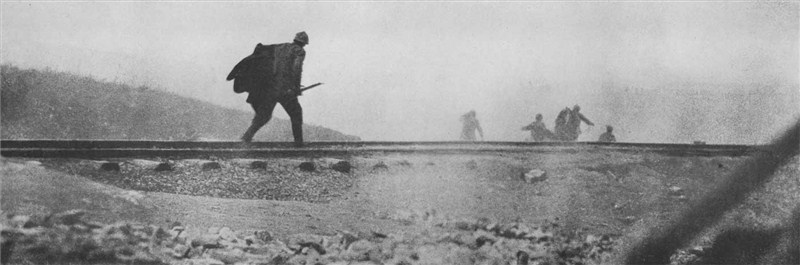

Pictured: landing at Gallipoli, April 1915.

Lord Kitchener put Sir Ian Hamilton in charge, but sent him into battle with out-of-date maps, inaccurate information and inexperienced troops. A force of British, French and ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corp) troops landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915. The Turks, who, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, had had time to prepare, were waiting for them in the hills above the beaches and unleashed a volley of fire that kept the Allied troops pinned down on the sand. The ANZACs managed to gain a foothold on what became known as ‘Anzac Cove’ but under sustained fire and faced with steep cliffs, were unable to push inland. The British, likewise, were unable to make any headway. Continue reading

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’.

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’. Born in Edinburgh, on 19 June 1861, Douglas Haig was the eleventh son of a wealthy whiskey distiller. An expert horseman, he once represented England at polo. In 1898, he joined the forces of

Born in Edinburgh, on 19 June 1861, Douglas Haig was the eleventh son of a wealthy whiskey distiller. An expert horseman, he once represented England at polo. In 1898, he joined the forces of  Wilhelm II, King George V of Britain and

Wilhelm II, King George V of Britain and  Born in Berlin on 20 January 1877, Karl Hans Lody spoke perfect English with an American accent, having been married to an American and living in Nebraska. Having obtained a US passport under the name Charles A. Inglis, which allowed him to travel freely,

Born in Berlin on 20 January 1877, Karl Hans Lody spoke perfect English with an American accent, having been married to an American and living in Nebraska. Having obtained a US passport under the name Charles A. Inglis, which allowed him to travel freely,  The Emperor of the Austrian-Hungarian (Habsburg) Empire, Franz Joseph, had ruled since 1848, and was to do so until his death in 1916, aged 86, a rule of 68 years. When his nephew and heir presumptive, Archduke Franz Ferdinand announced his desire to marry Sophie Chotek it sent shockwaves through the royal family. For Sophie,

The Emperor of the Austrian-Hungarian (Habsburg) Empire, Franz Joseph, had ruled since 1848, and was to do so until his death in 1916, aged 86, a rule of 68 years. When his nephew and heir presumptive, Archduke Franz Ferdinand announced his desire to marry Sophie Chotek it sent shockwaves through the royal family. For Sophie,

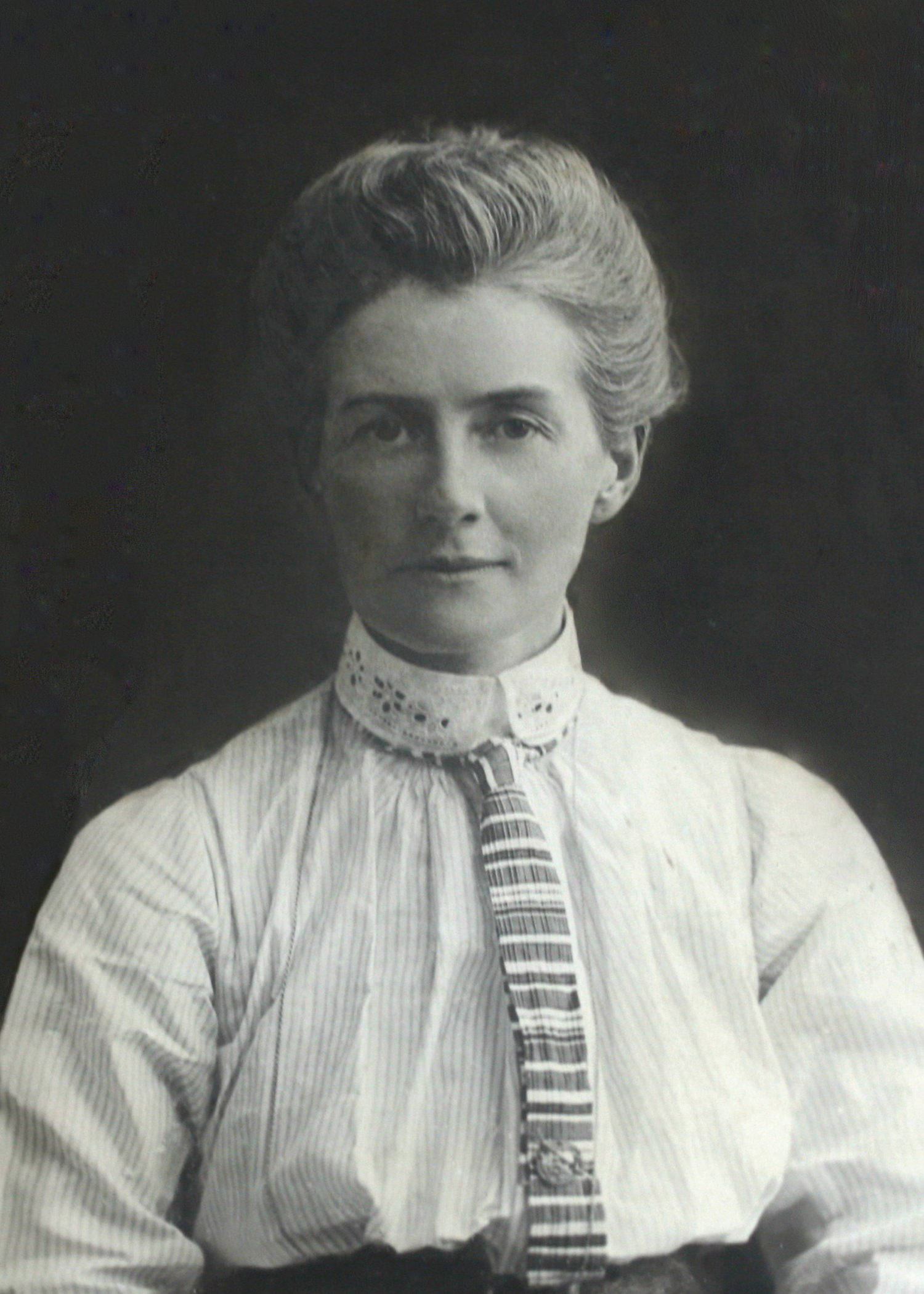

Following the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell refused the German offer of safe conduct into neutral Netherlands. She continued her work and in the process hid

Following the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell refused the German offer of safe conduct into neutral Netherlands. She continued her work and in the process hid  Churchill had been appointed to the Admiralty in October 1911, and had continued the policy established by his predecessor of keeping Britain ahead of the Germans and strengthening the navy by expanding the number of Dreadnoughts, the most powerful battleship of the time.

Churchill had been appointed to the Admiralty in October 1911, and had continued the policy established by his predecessor of keeping Britain ahead of the Germans and strengthening the navy by expanding the number of Dreadnoughts, the most powerful battleship of the time.