Proclaimed on 23 September 1943, the Italian Social Republic was a short-lived state headed by fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini.

The war had been going badly for Mussolini’s Italy, so much so that a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 25 July 1943 voted to have Mussolini removed. One of those who voted against Mussolini was his son-in-law, Galeazzo Ciano. The following day, Mussolini was dismissed by the Italian king, Victor Emmanuel III: ‘My dear Duce, it’s no longer any good. Italy has gone to bits… The soldiers don’t want to fight any more… At this moment you are the most hated man in Italy.’

The war had been going badly for Mussolini’s Italy, so much so that a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 25 July 1943 voted to have Mussolini removed. One of those who voted against Mussolini was his son-in-law, Galeazzo Ciano. The following day, Mussolini was dismissed by the Italian king, Victor Emmanuel III: ‘My dear Duce, it’s no longer any good. Italy has gone to bits… The soldiers don’t want to fight any more… At this moment you are the most hated man in Italy.’

Mussolini was immediately arrested and imprisoned. His successor, Pietro Badoglio, appointed a new cabinet that, pointedly, contained no fascists. The Italian population rejoiced.

On 8 September, Italy swapped sides and joined the Allies and, on 13 October 1943, declared war on Germany.

Salo

Meanwhile, Mussolini was kept under house arrest and frequently moved in order to keep his whereabouts hidden. On 26 August, he was moved into the Campo Imperatore Hotel, part of a ski resort high up in the mountains of Gran Sasso in the Abruzzo region of central Italy. It was here, on 12 September, that Mussolini was dramatically rescued.

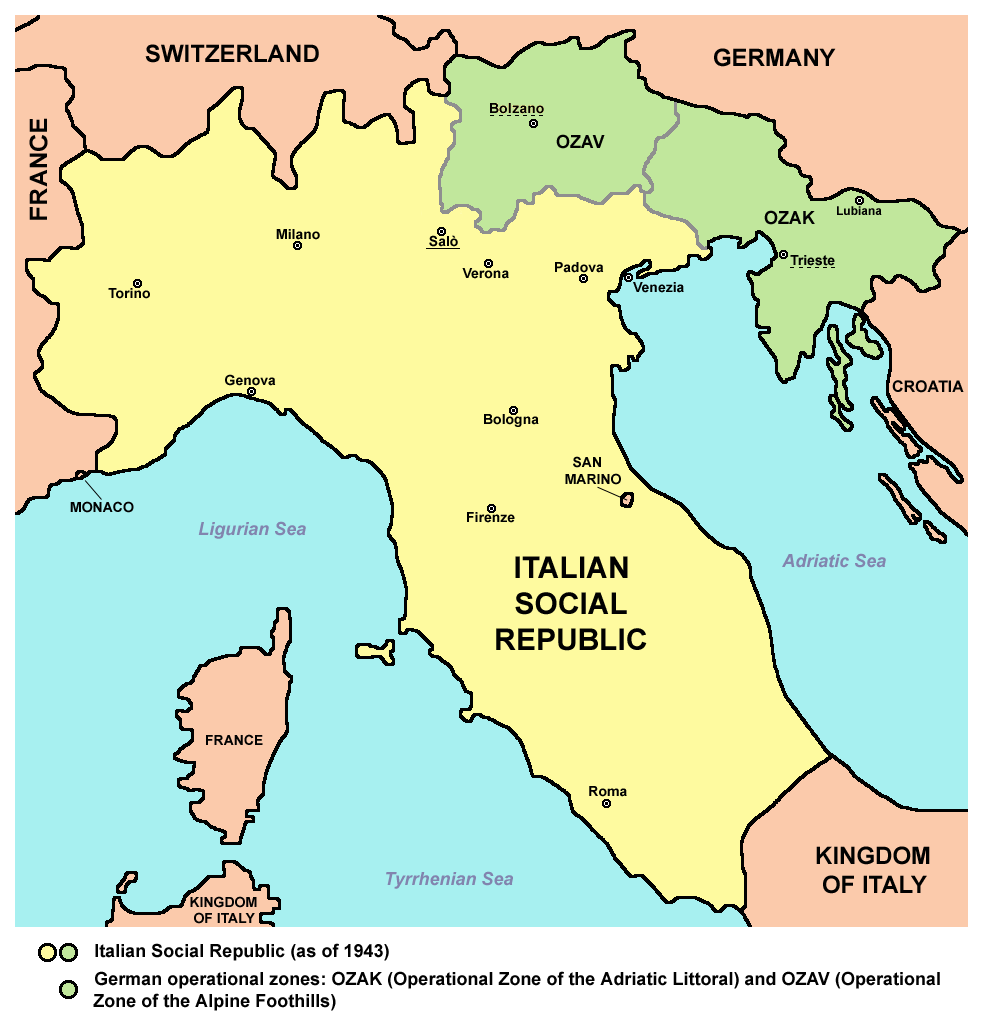

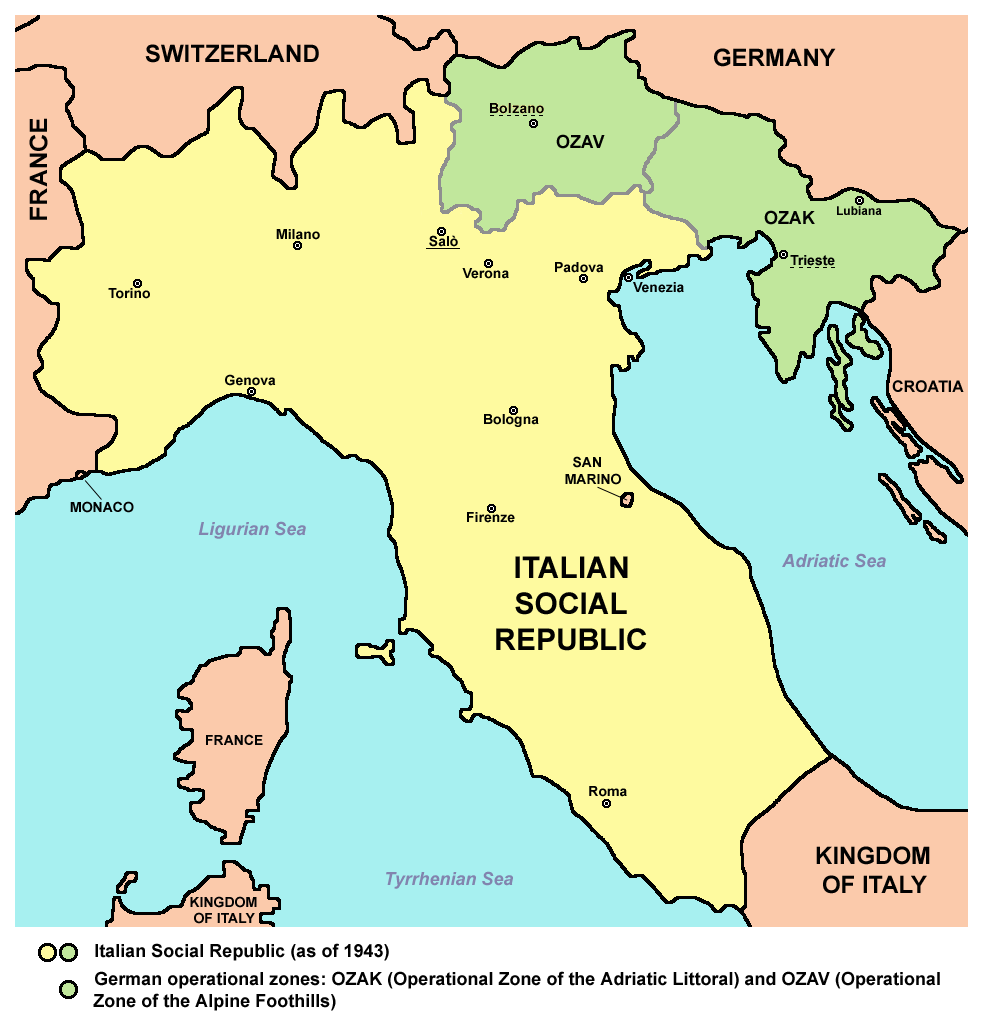

On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook.

On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook.

Having established his make-believe republic, Mussolini’s first priority was to deal with his son-in-law and other ‘traitors’ who had voted against him at the Fascist Grand Council meeting in July. Ciano had gone to Germany only to be forced back to Mussolini’s new republic. Despite the pleas of his daughter and Ciano’s wife, Edda, Mussolini had Ciano and five colleagues tried in Verona in January 1944, and five, including Ciano, were executed by firing squad on 11 January. To add to the humiliation, they were tied to chairs and shot in the back. Ciano’s last words were ‘Long live Italy!’

Although the Italian Social Republic had its own army, numbering about 150,000 men, its own flag (pictured) and currency, Mussolini’s power was limited and any decision had to be agreed upon by Berlin. His choice of men to serve in his new government was vetoed by his German masters. The republic had no constitution, was financially dependent on Germany and, as a new, supposedly independent state, was not officially recognized by any nation beyond Germany, Japan and their allies.

Although the Italian Social Republic had its own army, numbering about 150,000 men, its own flag (pictured) and currency, Mussolini’s power was limited and any decision had to be agreed upon by Berlin. His choice of men to serve in his new government was vetoed by his German masters. The republic had no constitution, was financially dependent on Germany and, as a new, supposedly independent state, was not officially recognized by any nation beyond Germany, Japan and their allies.

The Ardeatine Massacre

The local Italian resistance movement, whose confidence grew with every passing month, continually undermined the republic’s stability. But their activities often resulted in tragedy. On 23 March 1944, for example, the resistance exploded a bomb in Rome that killed 33 German soldiers. Retaliation was swift and brutal – for each German soldier killed, Hitler ordered the execution of ten Italian civilians. The following day, 335 Italians were shot in a sickening act of retribution in what became known as the Ardeatine Massacre. Meeting Hitler in April 1944, Mussolini protested but was ignored.

He may have wanted to try again at his next meeting with Hitler. The date of this meeting was 20 July 1944, the day Hitler survived the most serious attempt on his life. While the 20 July plotters were hunted down, Hitler, still a little shaky, kept his appointment and met Mussolini at the train station.

The Last Italian

While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife, Rachele, and various children and grandchildren. But it was far from domestic bliss. His daughter, Edda, never forgave her father for executing Ciano: ‘The Italian people must avenge the death of my husband. If they do not, I’ll do it with my own hands.’ Mussolini’s mistress, Clara Petacci (pictured), set up home nearby, much to Rachele’s disgust. (Indeed, was she placed there by the Germans to act as an informant?) Wife and mistress frequently argued while Mussolini, the diminished dictator, cowered. Mussolini himself suffered from ill-health and lost so much weight that one colleague described him as a ‘walking corpse’.

While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife, Rachele, and various children and grandchildren. But it was far from domestic bliss. His daughter, Edda, never forgave her father for executing Ciano: ‘The Italian people must avenge the death of my husband. If they do not, I’ll do it with my own hands.’ Mussolini’s mistress, Clara Petacci (pictured), set up home nearby, much to Rachele’s disgust. (Indeed, was she placed there by the Germans to act as an informant?) Wife and mistress frequently argued while Mussolini, the diminished dictator, cowered. Mussolini himself suffered from ill-health and lost so much weight that one colleague described him as a ‘walking corpse’.

Meanwhile, the Allies advanced northwards through Italy, breaking Germany’s heavily-fortified ‘Gustav Line’ on 11 May 1944, and liberating Rome on 4 June. By April 1945, the Allies had also breached the Gothic Line. With German forces retreating rapidly, the end for Mussolini and his Italian Social Republic was only a matter of time. But Mussolini could still talk big, promising to ‘fight to the last Italian’ and of turning Milan into the ‘Stalingrad of Italy’.

Epilogue to a tragedy

When even Mussolini realized all was lost, he conceded: ‘I am close to the end … I await the epilogue to this tragedy in which I no longer have a part to play.’

On 25 April, Mussolini and a few devoted followers, and his mistress, fled. Their destination was neutral Switzerland. Mussolini wrote a final letter to his wife in which the lifelong philanderer wrote, ‘You know you are the only woman I really loved.’

Meanwhile, the Italian Social Republic was no more. It had lasted just nineteen months.

On 26 April, Mussolini and his fleeing entourage were stopped by Italian partisans. Mussolini’s attempts to disguise himself with a Luftwaffe overcoat and helmet failed. On April 28, 1945, at the picturesque Lake Como, Mussolini and Petacci were executed; their bodies were heaped into the back of a van, and transported to Milan. There, in the city, their bodies were left to hang upside down for public display, from a rusty beam outside a petrol station.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

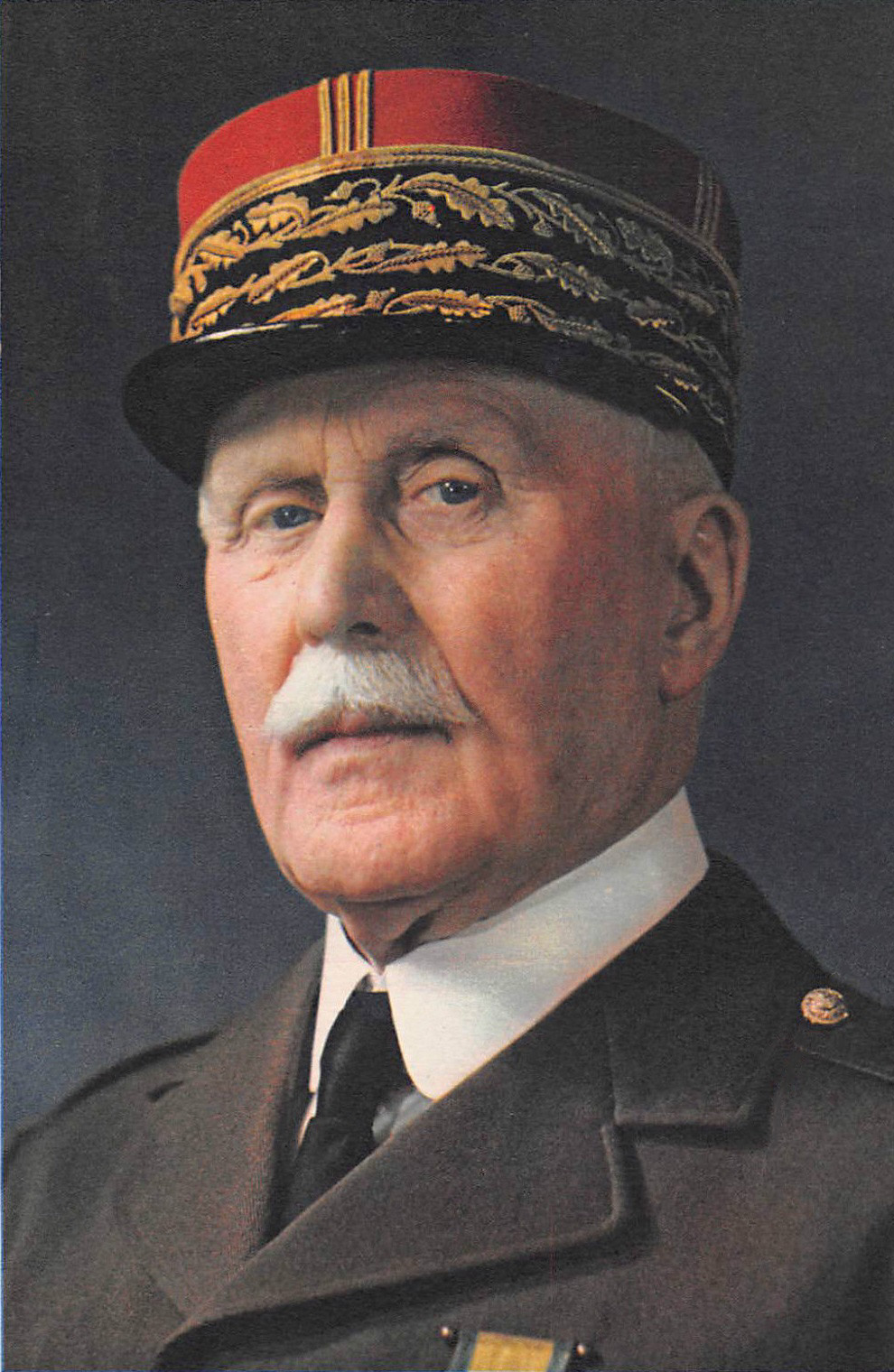

On 24 May 1941, the Bismarck, on its first operation, had helped sink the HMS Hood. But in return, it had been damaged and had set a course for northern France to attend to its wounds and repair the leaking fuel tanks. “The Hood was the pride of England,” said the German Fleet Commander, Admiral Günter Lutjens (pictured), over the ship’s loudspeakers, “the enemy will now attempt to concentrate his forces against us. The German nation is with you.”

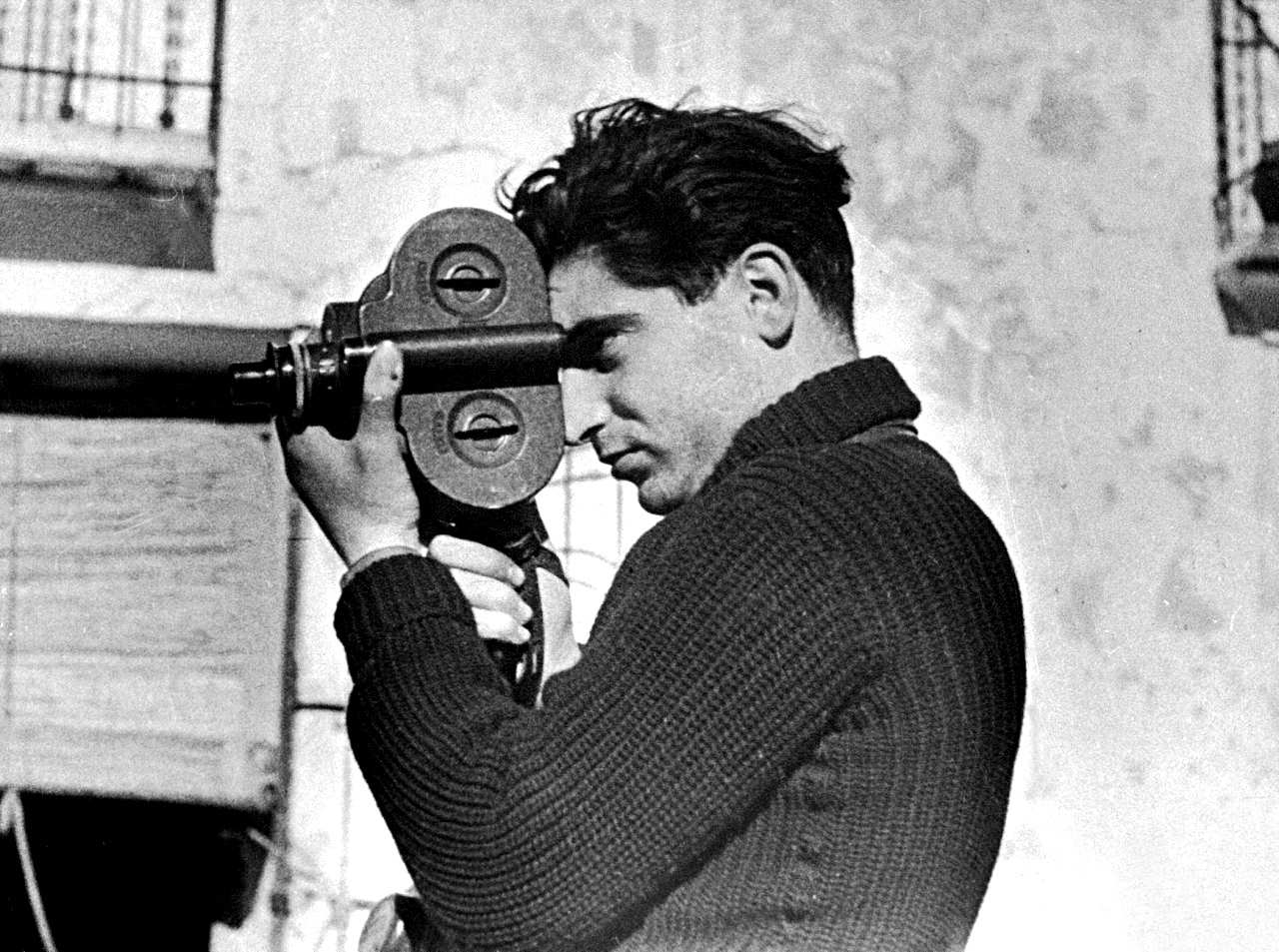

On 24 May 1941, the Bismarck, on its first operation, had helped sink the HMS Hood. But in return, it had been damaged and had set a course for northern France to attend to its wounds and repair the leaking fuel tanks. “The Hood was the pride of England,” said the German Fleet Commander, Admiral Günter Lutjens (pictured), over the ship’s loudspeakers, “the enemy will now attempt to concentrate his forces against us. The German nation is with you.” Born Andre Friedmann in Budapest on 22 October 1913, Robert Capa had, by the age of eighteen, turned into a political radical, opposed to the authoritarian rule of Hungarian regent, Miklós Horthy. In 1931, Friedmann was arrested and imprisoned by Hungary’s secret police. On his release, after only a few months, he moved to

Born Andre Friedmann in Budapest on 22 October 1913, Robert Capa had, by the age of eighteen, turned into a political radical, opposed to the authoritarian rule of Hungarian regent, Miklós Horthy. In 1931, Friedmann was arrested and imprisoned by Hungary’s secret police. On his release, after only a few months, he moved to

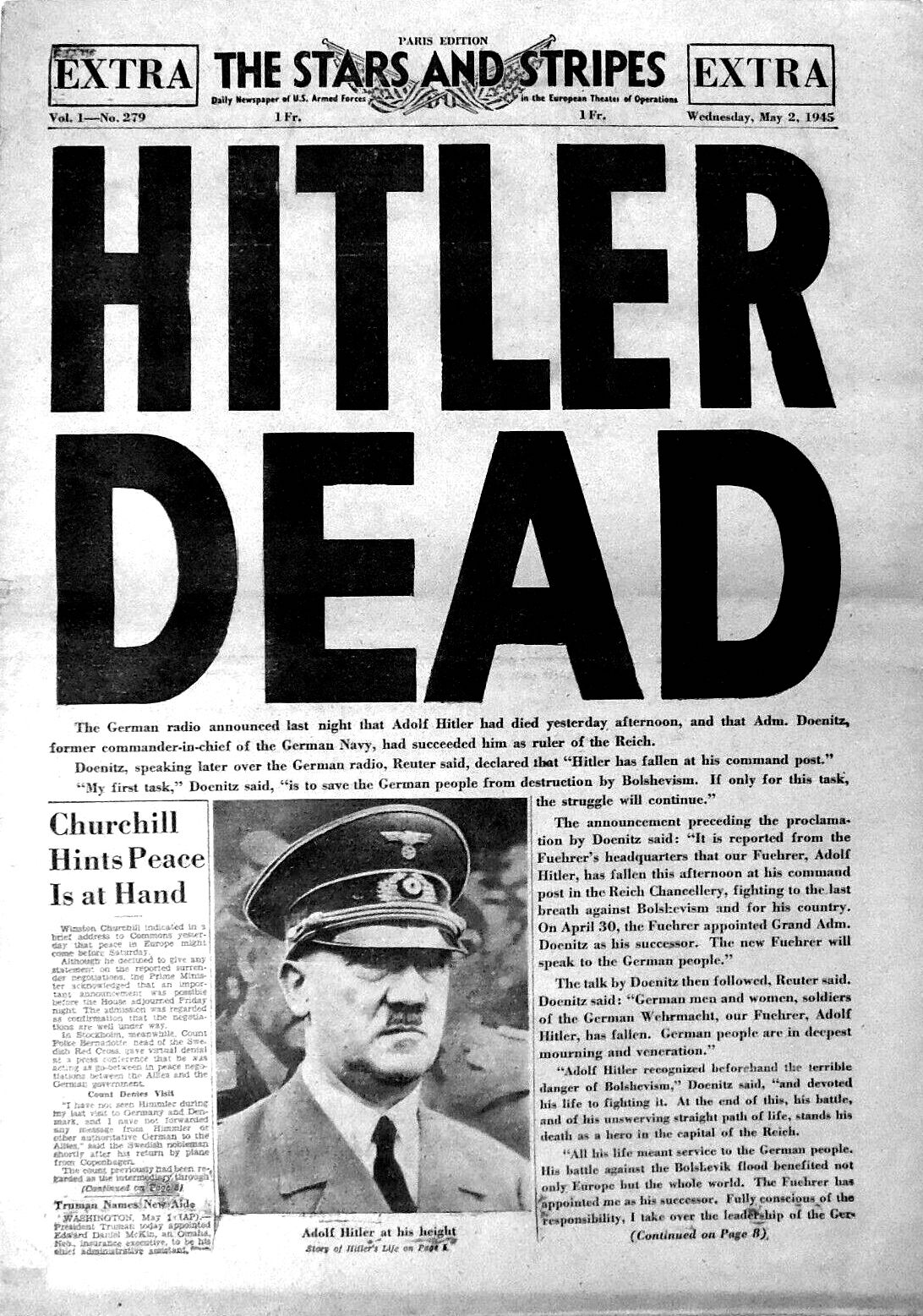

A week later, just past midnight on 29 April, in a ten-minute ceremony, Hitler married his long-term partner,

A week later, just past midnight on 29 April, in a ten-minute ceremony, Hitler married his long-term partner,

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to Nazi Germany, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to Nazi Germany, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on

Exercise Tiger

Exercise Tiger Hess was one of the original members of the Nazi Party, joining in 1920. Three years later he was involved in the failed

Hess was one of the original members of the Nazi Party, joining in 1920. Three years later he was involved in the failed  The war had been going badly for Mussolini’s Italy, so much so that a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 25 July 1943 voted to have Mussolini removed. One of those who voted against Mussolini was his son-in-law,

The war had been going badly for Mussolini’s Italy, so much so that a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 25 July 1943 voted to have Mussolini removed. One of those who voted against Mussolini was his son-in-law,  On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook.

On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook. While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife,

While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife,  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.