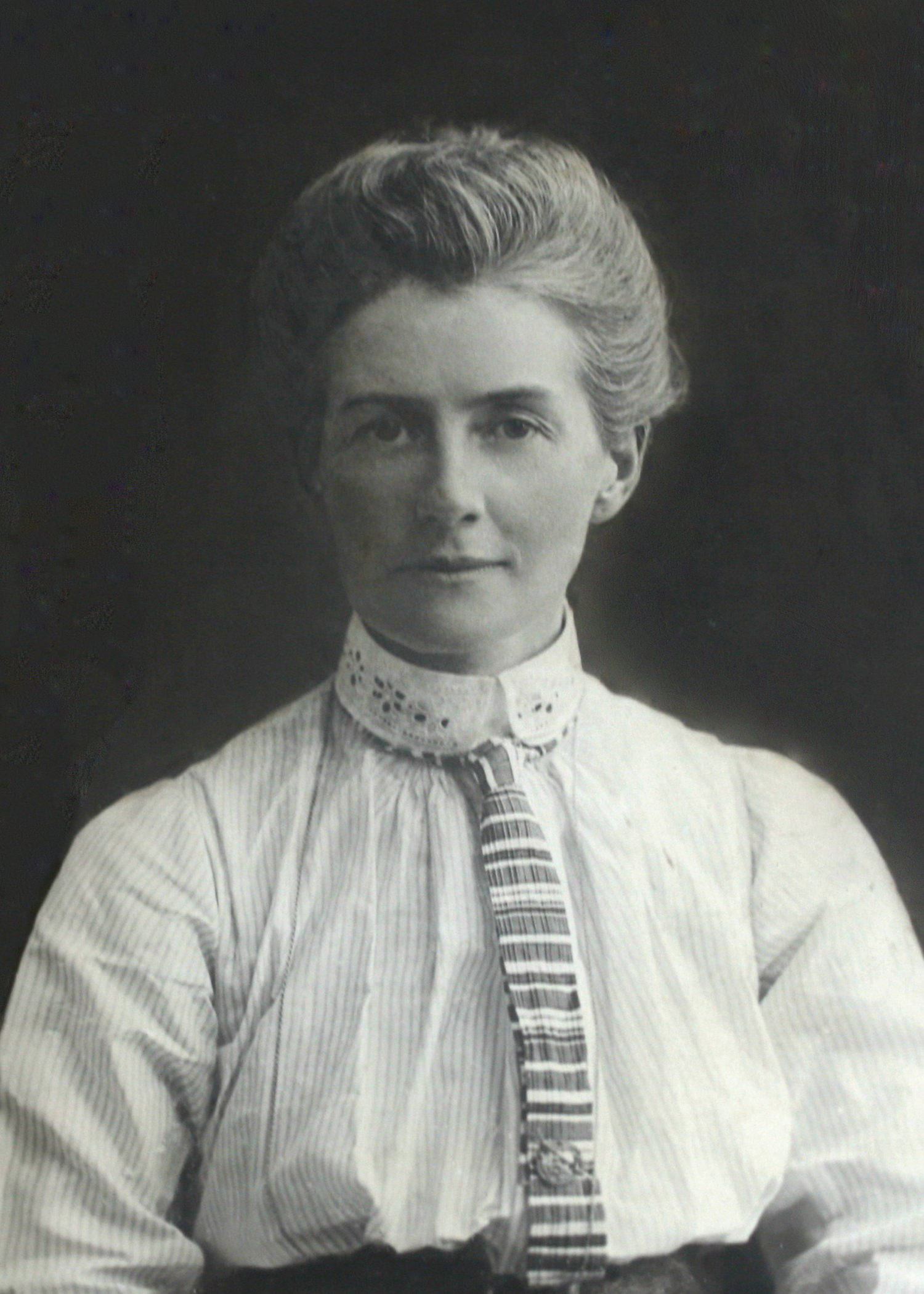

When the First World War broke out, Edith Cavell was working as a matron in a Brussels nursing school, a school she had co-founded in 1907 and where she’d helped pioneer the importance of follow-up care. But at the time, July 1914, she was on leave, holidaying with her family in Norfolk, England. On hearing the news of war, her parents begged her not to return to Belgium – but of course, she did.

Following the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell refused the German offer of safe conduct into neutral Netherlands. She continued her work and in the process hid refugee British, Belgian and French soldiers and provided over 200 of them the means to escape into the Netherlands from where most managed the journey back to England. With the Germans watching the work of the hospital, and its comings and goings, her arrest was inevitable. It duly came on 3 August 1915. Edith Cavell, arrested by the Germans, readily admitted her guilt.

Following the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell refused the German offer of safe conduct into neutral Netherlands. She continued her work and in the process hid refugee British, Belgian and French soldiers and provided over 200 of them the means to escape into the Netherlands from where most managed the journey back to England. With the Germans watching the work of the hospital, and its comings and goings, her arrest was inevitable. It duly came on 3 August 1915. Edith Cavell, arrested by the Germans, readily admitted her guilt.

‘Patriotism is not enough’

Cavell was remanded in isolation for ten weeks, not even being allowed to meet the lawyer appointed to defend her until the morning of her trial, a trial that lasted only two days. Cavell, along with 34 others, was found guilty. Her case became a cause célèbre but the British government, realising the Germans were acting within their own legality, was unable to intervene. However, the Americans, as neutrals, pointed to Cavell’s nursing credentials and her saving of the lives of German soldiers, as well as British, but to no avail. Along with her Belgian accomplice, Philippe Baucq, the nurse was found guilty and sentenced to be shot.

On the evening before her execution, Cavell was visited by an army chaplain. She told him, ‘Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.’ The words are inscribed on Cavell’s statue, near Trafalgar Square in London, pictured.

On the evening before her execution, Cavell was visited by an army chaplain. She told him, ‘Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.’ The words are inscribed on Cavell’s statue, near Trafalgar Square in London, pictured.

On 12 October 1915, about to face the firing squad, Cavell said, ‘My soul, as I believe, is safe, and I am glad to die for my country’. She was 49.

‘Judged justly’

The German foreign secretary, Alfred Zimmermann, expressed pity for Cavell but added that she had been ‘judged justly’. ‘I can assure you,’ wrote Zimmermann in a newspaper article, ‘that the case was conducted with the utmost thoroughness. No war court in the world could have given any other verdict.’ The fact that Cavell was a woman was of no relevance. But the decision to execute Cavell, however legal, was a localized one, unknown to the German army’s High Command or Wilhelm II, the German Kaiser. On hearing of the execution, the Kaiser was appalled, considering the sentence a political error.

Indeed, the British made propaganda capital out of the nurse’s execution, stoking up anti-German feelings by exploiting the image of the gentle nurse slaughtered by the German barbarian. Following the backlash, the other 33 accused had their death sentences commuted to imprisonment. In the weeks following Cavell’s execution, recruitment into the British Army doubled. The name Edith became popular – Edith Piaf, born two months after Cavell’s execution, was reputably named after her.

After the war, Cavell’s body was brought back to England where, in May 1919, she was afforded a state funeral at Westminster Abbey in London, attended by packed streets of mourners. A statue was erected in London’s Trafalgar Square, another on the grounds of Norwich cathedral, and another in Paris. In June 1940, following Nazi Germany’s invasion and occupation of France, Adolf Hitler personally ordered the destruction of Edith Cavell’s monument. The London memorial, designed by Sir George Frampton, was not well received on its unveiling in 1920. One reviewer wrote, ‘the figure of Edith Cavell is a beautiful conception, finely executed, but it is overshadowed and dwarfed by the great mass of granite which forms the background; and the squat figure representing Humanity, surmounting it, is as unpleasing as it is curious’.

Edith Cavell is buried at Norwich cathedral and each October, on the anniversary of her death, a service of remembrance is held at her grave.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to World War One, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.