On 22 April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, French and Algerian soldiers, fighting together, noticed a strange yellow-grey–coloured cloud floating across no man’s land in their direction. As it descended over them, many collapsed, coughing and wheezing, gasping for air, frothing at the mouth.

Men nearby watched as their colleagues fell to the ground in agony yet there were no gunshots to be heard and they appeared not to be visibly wounded in any way. Seized by panic, they bolted, throwing away their rifles, and even their tunics so that they might run faster, leaving a hole some four miles wide. But the Germans, wary of stepping into the cloud of poison gas protected only by their crude gasmasks, felt unable to exploit the opportunity. This, with 400 tones of chlorine gas, was the world’s first successful chemical weapon attack, resulting in the deaths of some 6,000 Allied soldiers.

This new terrible weapon was inhumane, cried the Allied generals, only to be using it themselves within five months. Britain’s first use of chlorine gas, at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, was not a great success. Sir John French and the British commanders had banned the use of the word ‘gas’, believing it too provocative a word; instead, they called it the ‘accessory’, a vague euphemism if ever there was one. Having waited for a favourable wind, they released the gas from cylinders. But the wind turned and the gas ended up causing greater causalities among the British than it did the Germans. (Pictured, Gassed by John Singer Sargent).

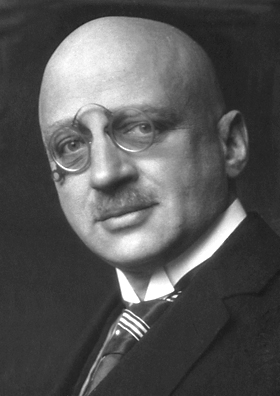

Fritz Haber

The pioneer of poison gas was a German called Fritz Haber, a Jew who, conscious of the anti-Semitism already prevalent in fin-de-siècle Germany, had, in 1893, converted to Christianity. Haber had developed the means to convert nitrogen in a way that it could be used to produce cheap and effective fertilizer, which, of course, improved and revolutionized agricultural efficiency. His work won him the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918.

The pioneer of poison gas was a German called Fritz Haber, a Jew who, conscious of the anti-Semitism already prevalent in fin-de-siècle Germany, had, in 1893, converted to Christianity. Haber had developed the means to convert nitrogen in a way that it could be used to produce cheap and effective fertilizer, which, of course, improved and revolutionized agricultural efficiency. His work won him the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918.

The use of poisonous gas in war was prohibited by the 1899 Hague Convention yet as soon as the First World War broke out Fritz Haber and his team worked on developing gas as a weapon. Haber, as a Jew, was determined to prove his devotion and loyalty to Germany. “During peacetime,” Haber once said, “a scientist belongs to the World, but during wartime, he belongs to his country”. Killing enemy troops with gas was, according to Haber, no worse than blowing their heads off with artillery. For his work, Haber was personally made an honorary captain by Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Clara Immerwahr

The successful use of chlorine gas at Ypres in April 1915 was, for the Germans, and Haber in particular, an occasion for celebration. But not so for Haber’s wife, Clara. Clara Immerwahr, who herself had been a successful chemist, had been appalled by her husband’s work, which she saw as a perversion of science. On 2 May, at their Berlin home, Haber hosted a party. While he and his friends toasted his success, Clara took her husband’s service revolver, went into their garden, and shot herself in the heart. She died the following morning in the arms of her 13-year-old son, Hermann.

The successful use of chlorine gas at Ypres in April 1915 was, for the Germans, and Haber in particular, an occasion for celebration. But not so for Haber’s wife, Clara. Clara Immerwahr, who herself had been a successful chemist, had been appalled by her husband’s work, which she saw as a perversion of science. On 2 May, at their Berlin home, Haber hosted a party. While he and his friends toasted his success, Clara took her husband’s service revolver, went into their garden, and shot herself in the heart. She died the following morning in the arms of her 13-year-old son, Hermann.

Despite the setback of his wife’s suicide, Haber was buoyed by his success with chlorine at Ypres but conscious of its limitations. He developed a new, more effective gas, called phosgene, which omitted a smell akin to hay. Its first use, on the Eastern front, in January 1916, proved successful. Those inflicted often showed no immediate ill effects but then would succumb, violently, some 48 hours later.

In 1917, the Germans introduced mustard gas, so named because of its odour, which could penetrate clothing and be absorbed through skin. Gas had become a common feature by the end of the war and although it was effective at incapacitating troops and causing long-term illness, gas accounted for only three percent of fatalities.

Post-war

Following the war, Fritz Haber continued his work. But, despite his Christian conversion, and despite his efforts on behalf of Germany’s war efforts, he was still a Jew, and hence felt very vulnerable once, in 1933, Hitler had come to power. On seeing many of his Jewish colleagues harassed, mistreated, and dismissed, Haber resigned. He emigrated to England in 1933 but, after only four months, decided to start afresh in Palestine. Stopping off in Basel in Switzerland, Haber, aged 65, died of a heart attack on 29 January 1934.

His son, Hermann, later emigrated to the US where, apparently ashamed by his father’s work, committed suicide in 1946.

Zyklon B

But the most tragic irony was that in his agricultural research, Haber helped develop pesticide gases, which included a cyanide-based pesticide called Zyklon B, indeed one of his assistants was credited as the official inventor of Zyklon B. Zyklon B was the main component used by the Nazis in their death camps. Among the six million killed in the gas chambers during the Holocaust were several members of Fritz Haber’s extended family, including his nieces and nephews.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to World War One, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.