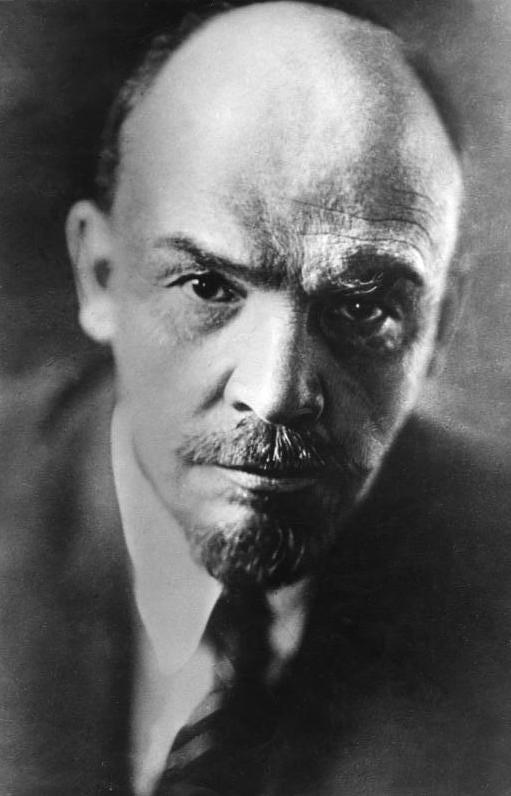

In December 1922, while recovering from a stroke, Bolshevik party leader, Vladimir Lenin, wrote his 600-word ‘Testament’ in which he proposed changes to the structure of the party’s Central Committee and commented on its individual members, comments that caused turmoil within the party leadership following his death in January 1924.

Lenin began his Testament with his concerns over the open antagonism between Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin, fearing that their hatred of each other would cause a split within the Centre Committee: ‘Relations between them make up the greater part of the danger of a split,’ he wrote. He suggested doubling the membership from 50 to 100.

Lenin began his Testament with his concerns over the open antagonism between Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin, fearing that their hatred of each other would cause a split within the Centre Committee: ‘Relations between them make up the greater part of the danger of a split,’ he wrote. He suggested doubling the membership from 50 to 100.

Trotsky

But it is Lenin’s judgements on individual members of the Centre Committee that make his Testament such a fascinating document. Leon Trotsky, for example, is described as ‘distinguished not only by outstanding ability. He is personally perhaps the most capable man in the present C.C., but he has displayed excessive self-assurance and shown excessive preoccupation with the purely administrative side of the work.’

Bukharin

Of Nikolai Bukharin, Lenin wrote, he is ‘rightly considered the favourite of the whole Party, but his theoretical views can be classified as fully Marxist only with the great reserve, for there is something scholastic about him.’

Pyatakov

There’s also mention of Georgy Pyatakov who is, in Lenin’s words, ‘unquestionably a man of outstanding will and outstanding ability, but shows far too much zeal for administrating and the administrative side of the work to be relied upon in a serious political matter.’

Kamenev and Zinoviev

Lenin also mentioned Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, who, following the Bolshevik seizure of power in the October Revolution of 1917, had dared to doubt Lenin. Both men resigned from the Centre Committee and Lenin had called them ‘deserters’ before they recanted and were welcomed back to the fold. However, Lenin never forgot what he called the ‘October Episode’, and in his Testament wrote that although the incident was ‘no accident … the blame for [the October Episode] cannot be laid upon them personally.’ But of course, by even referencing the episode, Lenin was drawing attention to it, ensuring that Kamenev and Zinoviev’s temporary loss of faith was not forgotten.

Stalin

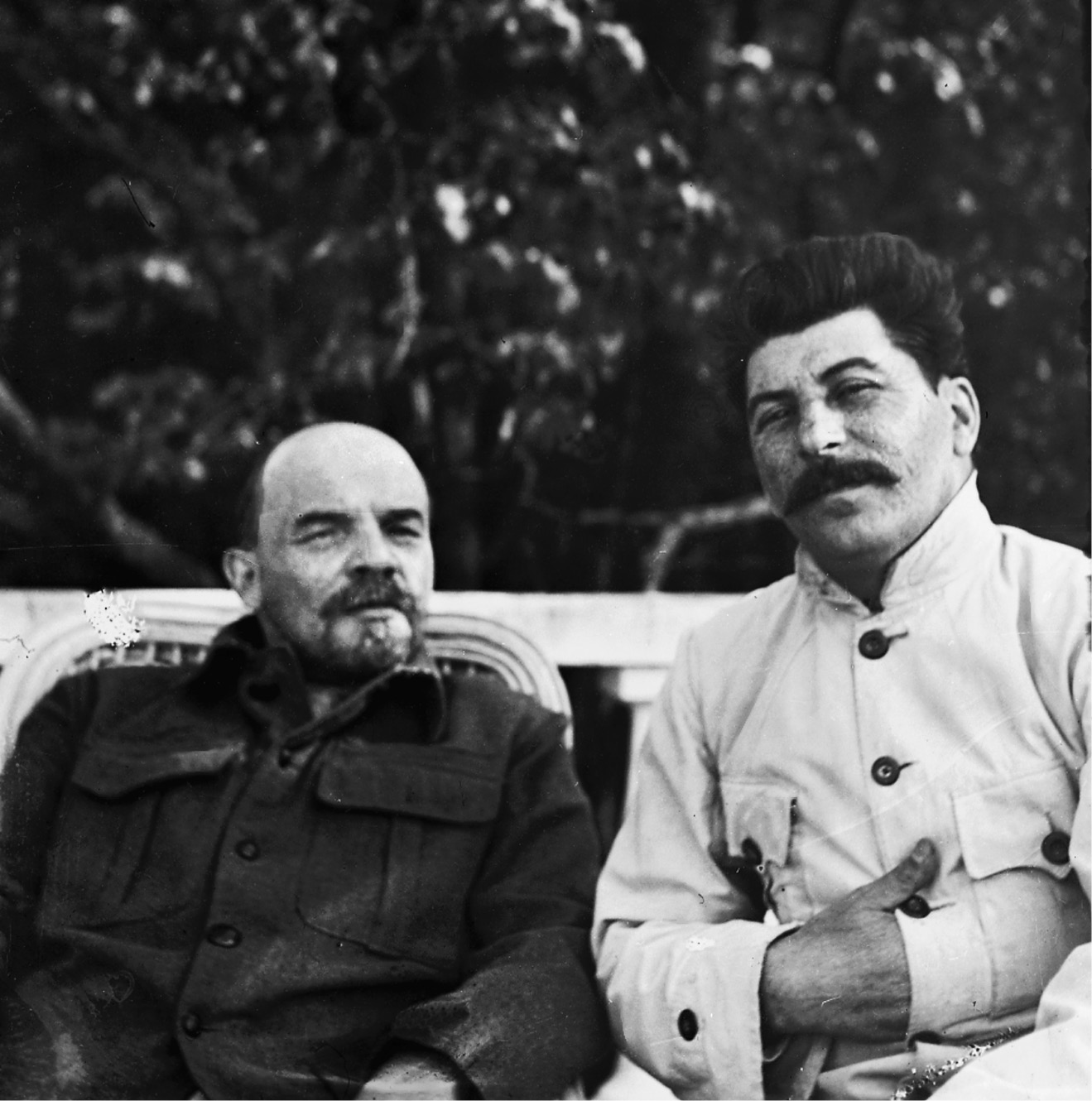

His most damning judgement however was reserved for Joseph Stalin (pictured with Lenin), whom Lenin had appointed General Secretary eight months earlier. Lenin was regretting his haste in promoting Stalin, questioning the amount of authority placed in the Georgian’s hands. While in the Testament other members of the Centre Committee received both criticism and praise, Stalin suffered only criticism. Lenin described Stalin as having ‘unlimited authority concentrated in his hands … I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution.’

His most damning judgement however was reserved for Joseph Stalin (pictured with Lenin), whom Lenin had appointed General Secretary eight months earlier. Lenin was regretting his haste in promoting Stalin, questioning the amount of authority placed in the Georgian’s hands. While in the Testament other members of the Centre Committee received both criticism and praise, Stalin suffered only criticism. Lenin described Stalin as having ‘unlimited authority concentrated in his hands … I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution.’

More damning still for Stalin, was Lenin’s 130-word addendum to his Testament, written a few days later, in which he declared:

‘Stalin is too rude and this defect, although quite tolerable in our midst and in dealing among us Communists, becomes intolerable in a Secretary-General. That is why I suggest the comrades think about a way of removing Stalin from that post and appointing another man in his stead who in all other respects differs from Comrade Stalin in having only one advantage, namely, that of being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite, and more considerate to the comrades, less capricious, etc.’

Nadezhda Krupskaya

Entrusted to his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s Testament was due to be read out at the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923 but, fatefully, Krupskaya kept it secret in the hope that her husband would recover. He did not.

Following Lenin’s death on 21 January 1924, Krupskaya insisted that the Testament be read out at the Thirteenth Party Congress, due in May 1924.

Kamenev and Zinoviev, together with Stalin, had formed a ruling triumvirate within the party’s leadership, mainly to keep Trotsky from assuming power. Lenin’s Testament had criticized all three. They could not allow such a damning document to be made public.

Stalin had offered to resign over the issue. The committee, including Trotsky, rejected his offer. Stalin had survived. Despite Krupskaya’s protests, only edited highlights were read out to party officials and Lenin’s misgivings were suppressed and were never permitted to be mentioned again.

They would all pay dearly for their support of the wily Georgian: Bukharin, Pyatakov, Kamenev and Zinoviev would all be executed within thirteen years, while Trotsky, living in exile in Mexico, would be assassinated by a Stalinist agent in August 1940 – all on the orders of Stalin.

Read more Soviet / Russian history in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Russian Revolution (80 pages) available as paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.