9 p.m. 27 February 1933, Berlin’s Reichstag building was set ablaze. By the time firefighters had arrived, the parliament building was already gutted. But the Reichstag Fire provided Hitler with a perfect excuse…

A communist outrage

Only four weeks earlier, Adolf Hitler had been appointed German Chancellor. On hearing the news of the fire at the Reichstag, Hitler and Joseph Goebbels were rushed (at 60 mph) to the site and there were met by a sweaty and overexcited Hermann Goering, who declared, ‘This is a communist outrage! One of the communist culprits has been arrested. Every Communist official must be shot where he is found. Every Communist deputy must this very night be strung up.’ Hitler agreed and saw the fire as a ‘God-given signal’ to impose his rule over the German people.

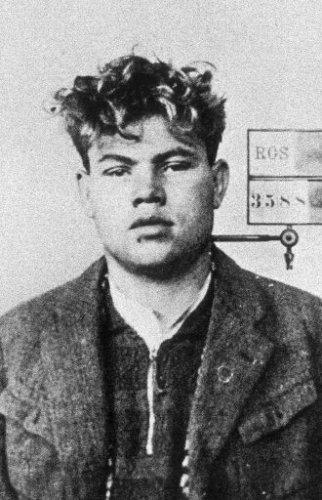

The ‘Communist culprit’ was 24-year-old Marinus van der Lubbe (pictured), an unemployed Dutch bricklayer, found half-naked on the premises, having used his shirt to start the fire.

The ‘Communist culprit’ was 24-year-old Marinus van der Lubbe (pictured), an unemployed Dutch bricklayer, found half-naked on the premises, having used his shirt to start the fire.

Van der Lubbe readily confessed to the crime, stating, ‘I considered arson a suitable method. I did not wish to harm private people but something belonging to the system itself. I decided on the Reichstag.’ But he denied any involvement with the communists.

For the protection of the people and state

The following day, 85-year-old Paul von Hindenburg, the increasingly senile German president, accepted Hitler’s request for a decree suspending all political and civil liberties as a ‘temporary’ measure for the ‘protection of the people and state’.

The communists, according to Hitler, were attempting a putsch, a revolt, and thousands of known communists were arrested, tortured and either murdered or placed in the newly-opened concentration camps for ‘protective custody’.

A bloody liar

So was the Reichstag fire the work of communists, as Hitler claimed? Although once associated with the Communist Party, van der Lubbe insisted he acted alone. But many, at the time and since, felt this unlikely. Van der Lubbe was, apparently, of limited intelligence and in his desire for attention had, more than once, persuaded the German press that he would swim the English Channel. With photographers and reporters poised, he coated himself in grease, and swam out a few yards, only to return declaring unfavourable currents. On another occasion van der Lubbe, following a strike at his workplace, offered to accept responsibility and take any reprimand as long as no one else was punished. It was obvious however to his employers that van der Lubbe had no or little involvement in stirring up the workers.

So was the Reichstag fire the work of communists, as Hitler claimed? Although once associated with the Communist Party, van der Lubbe insisted he acted alone. But many, at the time and since, felt this unlikely. Van der Lubbe was, apparently, of limited intelligence and in his desire for attention had, more than once, persuaded the German press that he would swim the English Channel. With photographers and reporters poised, he coated himself in grease, and swam out a few yards, only to return declaring unfavourable currents. On another occasion van der Lubbe, following a strike at his workplace, offered to accept responsibility and take any reprimand as long as no one else was punished. It was obvious however to his employers that van der Lubbe had no or little involvement in stirring up the workers.

Rumours persisted even at the time that the Nazis were implicated in starting the Reichstag Fire, if not the government, then the party. When the head of the Berlin SA, Karl Ernst, was asked about his involvement, he replied, ‘If I said yes, I’d be a bloody fool, if I said no I’d be a bloody liar’. It was rumoured that an underground passage ran all the way from Goering’s residence in Berlin to the Reichstag.

In the post-war Nuremberg trials, witnesses testified hearing Goering boast about setting the Reichstag on fire but Goering, who was to kill himself on 15 October 1946, the night before he was due to be executed, steadfastly denied any involvement.

But historians do now believe that Marinus van der Lubbe did indeed manage to set such a large building ablaze with just his shirt and a few matches.

The Reichstag Fire helped Hitler consolidate his power. The temporary suspension of liberties was never revoked and any active opposition to the Nazis was stifled. When, the following month, the last parliamentary elections took place, only Hitler, it was claimed, could save Germany from the Jews and communists. The SA intimidated all other parties into silence and the Nazis polled 44% of the vote, not enough for a majority but enough to squash any future political resistance.

The Enabling Act, passed in late March 1933, effectively did away with the constitution altogether. There would be no more elections or a constitution to keep Hitler in check.

Marinus van der Lubbe on trial

Marinus van der Lubbe and four others were put on trial, including Ernst Torgler, chairman of the German Communist Party and Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian communist who, in 1949 became Bulgaria’s prime minister. Tried by the German High Court, van der Lubbe was found guilty but Torgler and his companions were acquitted for the lack of evidence.

Hitler was furious with the acquittals and decreed that future cases of treason should be facilitated, not by the High Court, but by the People’s Court, where a guilty verdict was virtually a forgone conclusion.

On 10 January 1934, three days short of his twenty-fifth birthday, Marinus van der Lubbe was guillotined.

Seventy-four years later, in January 2008, the German state overturned the verdict against van der Lubbe and officially pardoned him.

Rupert Colley

Rupert Colley

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to Nazi Germany, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

In the post-war Nuremberg trials, witnesses testified hearing Goering boast about setting the Reichstag on fire but Goering, who was to kill himself on 15 October 1946, the night before he was due to be executed, steadfastly denied any involvement.