As 1914 drew to a close, the Western Front had become a permanent fixture of trenches stretching 400 miles from the English Channel to Switzerland. Stalemate ensued. A year later, the situation was no better. Each side looked for a ‘Big Push’ that would break the opposing line of defence and bring about victory. Rupert Colley summarises one such push – the Battle of Verdun.

‘France will bleed to death’

At the end of 1915, the German commander-in-chief, Erich von Falkenhayn, decided that Germany’s ‘arch enemy’ was not France, but Britain. But to destroy Britain’s will, Germany had first to defeat France. In a ‘Christmas memorandum’ to the German kaiser, Wilhelm II, Falkenhayn proposed an offensive that would compel the French to ‘throw in every man they have. If they do so,’ he continued, ‘the forces of France will bleed to death’. The place to do this, Falkenhayn declared, would be Verdun.

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’.

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’.

‘They shall not pass’

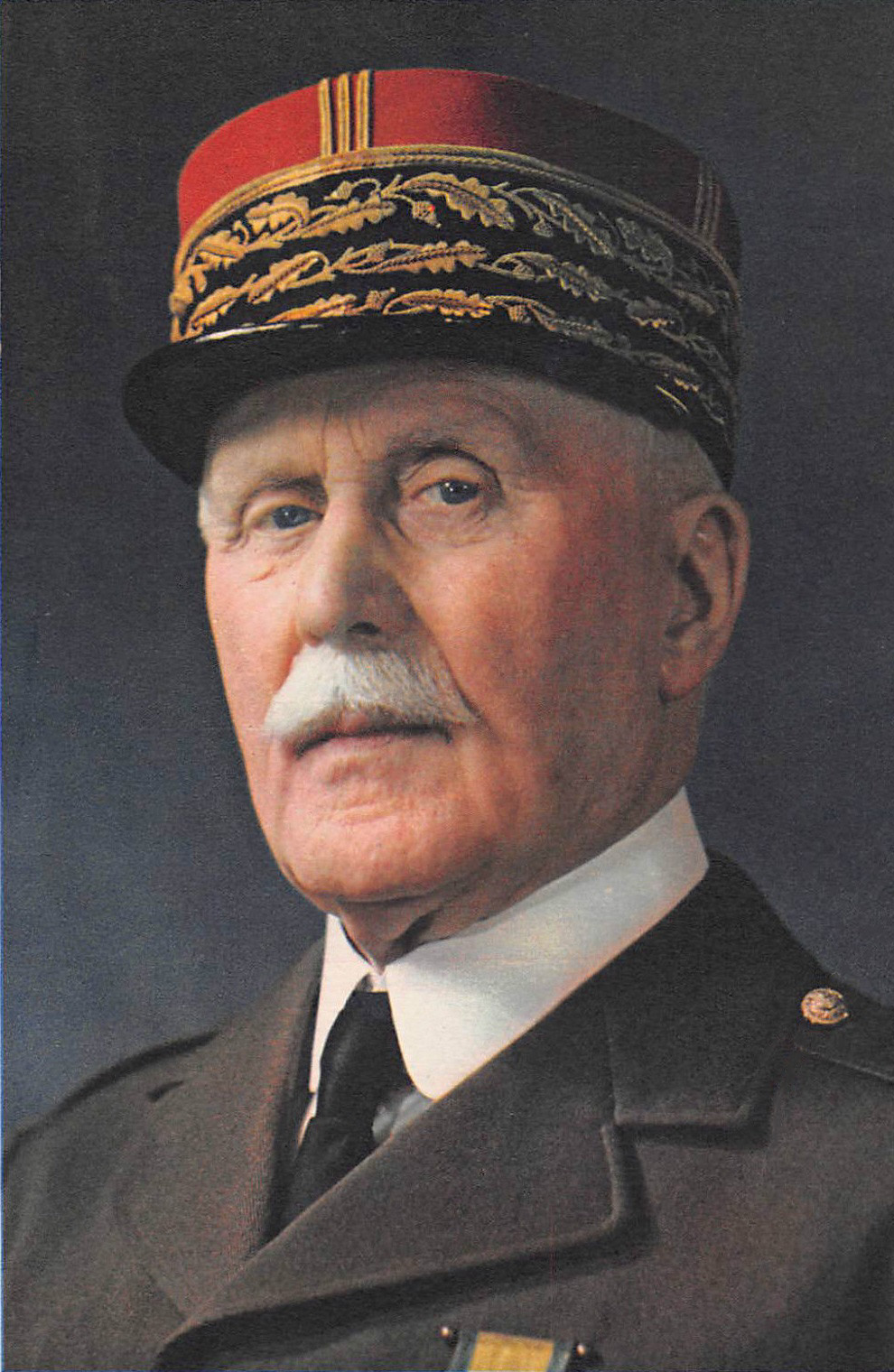

Galvanised into action, Joffre dispatched his top general, Henri-Philippe Pétain (pictured), to organise a stern defence of the city. Pétain managed to protect the only road leading into the city that remained open to the French. Every day, while under continuous fire, 2,000 lorries made a return trip along the 45-mile Voie Sacrée (‘Sacred Way’) bringing in vital supplies and reinforcements to be fed into the furnace that had become Verdun. Serving under Pétain was General Robert Nivelle who famously promised that the Germans on ne passe pas, ‘they shall not pass’, a quote often attributed to Pétain.

Galvanised into action, Joffre dispatched his top general, Henri-Philippe Pétain (pictured), to organise a stern defence of the city. Pétain managed to protect the only road leading into the city that remained open to the French. Every day, while under continuous fire, 2,000 lorries made a return trip along the 45-mile Voie Sacrée (‘Sacred Way’) bringing in vital supplies and reinforcements to be fed into the furnace that had become Verdun. Serving under Pétain was General Robert Nivelle who famously promised that the Germans on ne passe pas, ‘they shall not pass’, a quote often attributed to Pétain.

But the French were suffering grievous losses. Joffre demanded that his British counterpart, Sir Douglas Haig, open up the new offensive on the Somme, to the south of Verdun, to take the pressure off his beleaguered men. Haig, concerned that the new recruits to the British Army were not yet battle-ready, offered 15 August 1916 as a start date. Joffre responded angrily that the French army would ‘cease to exist’ by then. Haig brought forward the offer to 1 July.

During June 1916, the attack and counterattack at Verdun continued. On the Eastern Front, the Russians attacked the Austrians, who, in turn, appealed to the Germans for help. Falkenhayn responded by calling a temporary halt at Verdun and transferring men east to aid the Austrians.

The Battle of Verdun wound down, then fizzled out entirely, officially ending on 18 December 1916. The French, under the stewardship of Generals Pétain and Nivelle regained much of what they had lost. After ten months of fighting, the city had been flattened, and the Germans and French, between them, had lost 260,000 men – one death for every 90 seconds of the battle. Men on all sides were bled to death but ultimately, Falkenhayn’s big push achieved nothing.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to World War One, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.