In November 1914, the Ottoman Empire, entered the war on the side of the Central Powers and on Christmas Day went on the offensive against the Russians, launching an attack through the Caucasus. Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II sent an appeal to Britain, asking for a diversionary attack that would ease the pressure on Russia. From this came the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign.

Naval Assault

The British planned its diversionary attack, to use the Royal Navy to take control of the Dardanelles Straits from where they could attack Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. By capturing Constantinople, the British hoped then to link up with their Russian allies. The attack would, it hoped, have the additional benefit of drawing German troops away from both the Western and Eastern Fronts.

The Dardanelles, a strait of water separating mainland Turkey and the Gallipoli peninsula, is sixty miles long and, at its widest, only 3.5 miles. Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, insisted that the Royal Navy, acting alone, could succeed. On 19 February, a flotilla of British and French ships pounded the outer forts of the Dardanelles and a month later attempted to penetrate the strait. It failed, losing six ships (three sunk and three damaged), two-thirds of its fleet. Soldiers, it was decided, would be needed after all.

ANZACs

Pictured: landing at Gallipoli, April 1915.

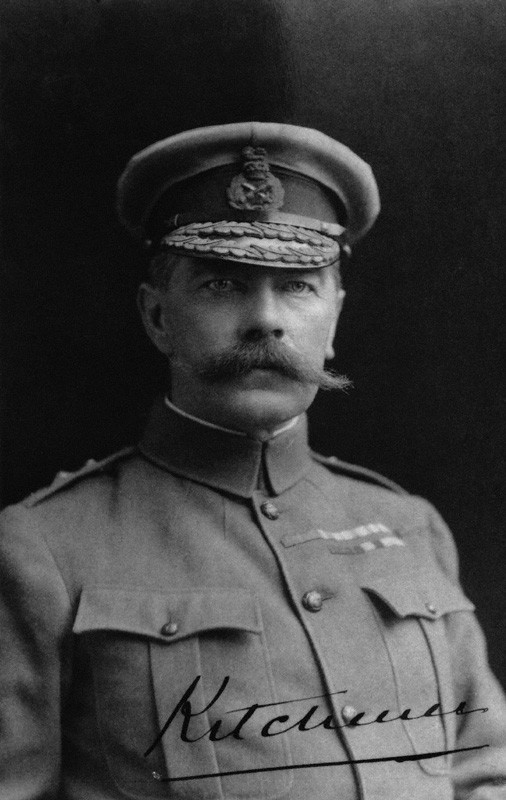

Lord Kitchener put Sir Ian Hamilton in charge, but sent him into battle with out-of-date maps, inaccurate information and inexperienced troops. A force of British, French and ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corp) troops landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915. The Turks, who, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, had had time to prepare, were waiting for them in the hills above the beaches and unleashed a volley of fire that kept the Allied troops pinned down on the sand. The ANZACs managed to gain a foothold on what became known as ‘Anzac Cove’ but under sustained fire and faced with steep cliffs, were unable to push inland. The British, likewise, were unable to make any headway.

As on the Western Front, stalemate ensued. The Turks were not the pushover the British had hoped for. The Allies, under constant attack, took cover as best as they could among the rocks, with only the beach behind them and, without shade, exposed to the searing sun. Their fallen comrades lay putrefied and bloated beside them, the stench filling the air.

Sulva Bay

On 6 August, the British launched a renewed attack. The ANZACs would attempt to break out from their beach and take the high ground whilst a British contingent of 20,000 new troops led by General Sir Frederick Stopford would land on Sulva Bay on the north side of Gallipoli.

Stopford’s men made a successful landing, outnumbering the enemy by 15 to one. But instead of pressing home their advantage, the general gave his men the afternoon off to enjoy the sun while he had a snooze. Hamilton advised but did not order an advance. By the time Stopford did advance, it was too late – the Turks had rushed men into position and the stalemate of before prevailed. (Pictured: Australian troops, 9 August 1915).

The Allied troops endured further months of misery. Seventy percent of the ANZACs suffered from dysentery, where medical care, unlike the Western Front, was at best primitive.

Evacuation

With the onset of winter, the troops, without shelter and exposed to the elements, suffered frostbite. In October, Hamilton was replaced by Charles Monro, who recommended an end to the campaign. Kitchener was dispatched by the British government to check on the situation. Appalled at what he saw and persuaded by Monro, he returned to London and urged evacuation. Finally, in January 1916, the curtain fell on the whole sorry ‘side show’, the last troops leaving on 9 January.

The campaign had indeed diverted Turkish forces away from Russia but it was considered a complete failure, one that cost 140,000 Allied casualties. Churchill, contrite, resigned and punished himself by joining a company of Royal Scot Fusiliers on the Western Front. (He returned to politics a year later and in 1917 was appointed Minister of Munitions). Meanwhile, Kitchener, who had been progressively side-lined, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Russia. On 5 June 1916, his ship, the HMS Hampshire, hit a German mine off the Orkney Islands and sunk. His body was never found.

The campaign had indeed diverted Turkish forces away from Russia but it was considered a complete failure, one that cost 140,000 Allied casualties. Churchill, contrite, resigned and punished himself by joining a company of Royal Scot Fusiliers on the Western Front. (He returned to politics a year later and in 1917 was appointed Minister of Munitions). Meanwhile, Kitchener, who had been progressively side-lined, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Russia. On 5 June 1916, his ship, the HMS Hampshire, hit a German mine off the Orkney Islands and sunk. His body was never found.

The failure of Gallipoli also heralded the end of Herbert Asquith as prime minister – on 25 May 1915, his Liberal government was forced into a coalition, and on 5 December 1916, he was replaced as prime minister by David Lloyd George.

25 April, the date the ANZACs initially landed in Gallipoli in 1915, is now marked annually as a day of remembrance, known as Anzac Day.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to World War One, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.