Recently I enjoyed a few days in Guernsey and visited the German Museum of Occupation. It was strange seeing images of familiar English scenes: the country lane with a red telephone box to one side – with a Nazi walking past; or a church with its spire and, nearby, a swastika flag fluttering in the breeze. Yes, this was Britain and for five long years, the Nazis had occupied a very small part of it.

Vulnerable

There was, at the start of the Second World War, a small British garrison stationed on the Channel Islands but Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime prime minister, decided that the Islands could not be defended and were to be demilitarized.

Of the pre-war population of 96,000, a quarter was evacuated to Britain. On 21 June 1940, the last British soldiers also departed and, in doing so, left the remaining islanders to their fate. The Germans, unaware of this and that the Islands were there for the taking, bombed the Guernsey and Jersey harbours on 28 June, killing 44 civilians. Two days later, on 30 June, the island of Guernsey surrendered, swiftly followed by Jersey, Alderney and Sark.

The only part of Great Britain to be occupied by the Germans throughout the war, the islands were not of any strategic importance for the Germans beyond denying the British the option of using them as a base. Also, the occupation of British territory was symbolically important to the Germans. In the early years, the islands were used as a holiday destination for German troops serving in France.

The Nazis take control

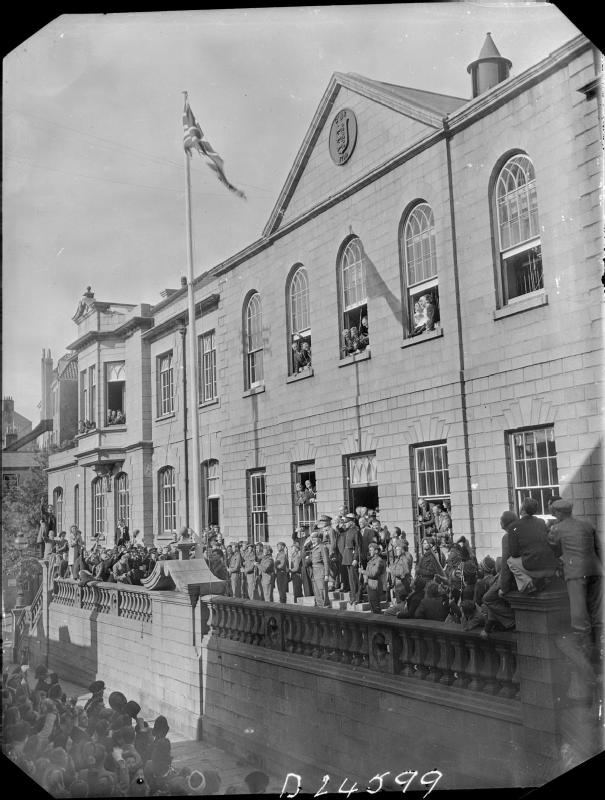

German soldiers standing in King Street, Saint Helier, during the Occupation of Jersey

Immediately the occupiers established control and stamped their authority. It was often the seemingly inconsequential things that irked the most: the changing of the time to fit in with German time; changing which side of the road to drive on. But as most cars were requisitioned by the Germans and fuel was heavily rationed, it made little difference and horse-drawn traffic was soon a regular sight on the Guernsey roads.

Using forced labour imported from across occupied Europe, the Germans fortified the islands and built an underground hospital for their troops wounded in France. Four concentration camps were also built on Alderney, an island which had largely been evacuated before the invasion. One of the Alderney camps was specifically for Jews and islanders who had had just one Jewish grandparent were deemed Jewish and were therefore especially vulnerable. British police officers in British police uniforms were used to arrest the Islands’ Jews.

Concentration camps on British soil

The camps, the only concentration camps on British soil, opened in January 1942 and, with a capacity of about 6,000, held prisoners from all over Europe. They were designed to house forced labourers rather than exterminate but, nevertheless, the camps saw the death of over 700 inmates during the two years of their existence. The camps were closed in 1944 and the survivors were transported to Germany. For many the death camps awaited.

The islanders had received orders from London not to resist but the intensity of occupation, with almost one German for every two islanders, rendered active resistance virtually impossible anyway. But individual acts of defiance and heroism were common. The most daring examples were islanders who hid those in danger of internment.

British citizens deported

In 1942, as a reprisal for German civilians taken by the British in Iran, Hitler decreed that citizens not born on the islands were to be deported to camps in Germany. Some 2,000 British citizens were deported, many never to return.

The supply of food and fuel from Germany through France, although rationed, had not been a severe problem until the Allied Normandy Invasion in June 1944. Once the Allies had secured northern France, supplies to the islands came to an abrupt halt. Churchill considered opinion of the situation was to “let them rot”. Both occupier and occupied starved and it wasn’t for another six months, in December 1944, that the first International Red Cross ship arrived with much-needed supplies.

Our dear Channel Islands

Channel Islands Liberated

On 8 May, the war in Europe ended. Broadcasting from London, Churchill announced the “unconditional surrender of all German land, sea and air forces in Europe.” He added, “and I should not forget to mention that our dear Channel Islands, the only part of His Majesty’s Dominions that has been in the hands of the German foe, are also to be freed today.”

The German occupiers of the Channel Islands surrendered unconditionally and, early in the morning, 9 May, the first ships bearing the Islanders’ liberators docked.

Immediately the celebrations began: processions, parties, speeches, prayers, the singing of the National Anthem and the raising of the Union Jack. But also the reprisals began: women who had fraternised with the Germans, ‘Jerry Bags’, were particularly vulnerable to swift justice. Known collaborators and informants were also targeted. Accusations of collaboration were investigated with the view to prosecution but none came to court.

On 7 June, King George and Queen Elizabeth visited the islands. By the end of 1945, all those evacuated off the islands during the spring of 1940 had returned home.

Total collaboration

And there ends the tale of stoical resistance and British stubbornness and pride. But beneath it all lurks the unsavoury taint of collaboration: “the Channel Islands’ war history was one of almost total collaboration with the Nazis,” wrote Julia Pascal, author of Theresa, a play about wartime Guernsey. Pascal, writing in The Guardian in September 2002, goes on to say, “Many on Guernsey believe that the Channel Islands government willingly served their Nazi masters… The occupation has been bleached out of British history.”

But the Islanders of today will still celebrate Liberation Day each year.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

Although…not all Germans were, or agreed with Nazi ideal or policy.