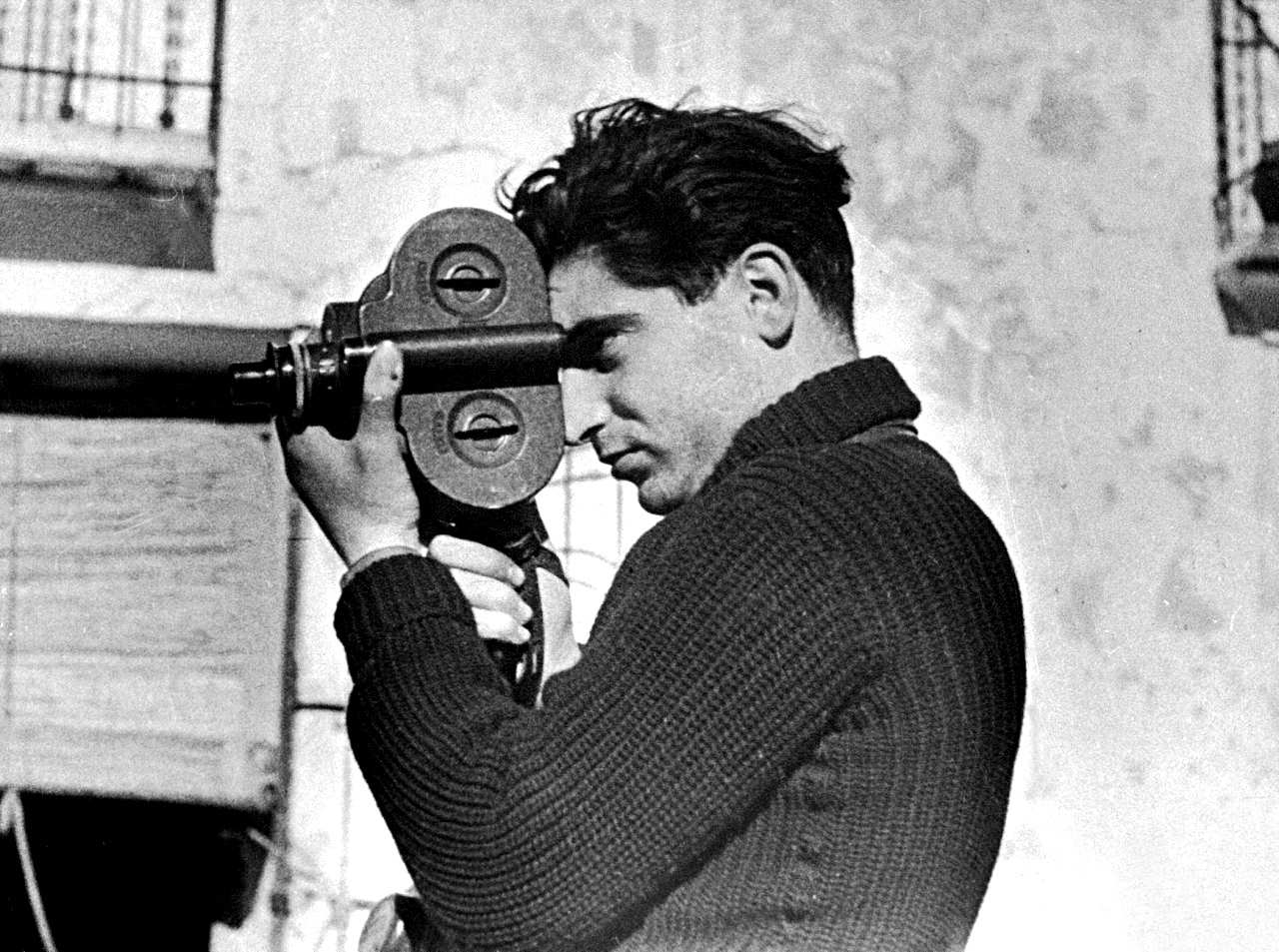

‘If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.’

Considered one of the greatest war photographers, Robert Capa’s images, especially those taken during the Spanish Civil War and the D-Day landings, are among the iconic images of the twentieth century.

Born Andre Friedmann in Budapest on 22 October 1913, Robert Capa had, by the age of eighteen, turned into a political radical, opposed to the authoritarian rule of Hungarian regent, Miklós Horthy. In 1931, Friedmann was arrested and imprisoned by Hungary’s secret police. On his release, after only a few months, he moved to Berlin where he studied journalism and political science while working part-time as a dark room apprentice. In 1933, alarmed by the rise of Nazism, Friedmann, who was Jewish, moved to Paris.

Born Andre Friedmann in Budapest on 22 October 1913, Robert Capa had, by the age of eighteen, turned into a political radical, opposed to the authoritarian rule of Hungarian regent, Miklós Horthy. In 1931, Friedmann was arrested and imprisoned by Hungary’s secret police. On his release, after only a few months, he moved to Berlin where he studied journalism and political science while working part-time as a dark room apprentice. In 1933, alarmed by the rise of Nazism, Friedmann, who was Jewish, moved to Paris.

Famous American photographer

Two years later, while in Paris, Friedmann met Gerta Pohorylle, a German Jew who had also fled Hitler’s Germany. Together they worked as photojournalists, fell in love and, in an attempt to make their work more commercially appealing, pretended they both worked for the famous American photographer, Robert Capa. Friedmann took the photos, Pohorylle hawked them to the news agencies, and credit was given to the fictional Robert Capa. (The name ‘Capa’ was chosen as homage to the American film director, Frank Capra.)

The Falling Soldier

In 1936, Friedmann, having now assumed the name Robert Capa, and Pohorylle, who had also changed her name, becoming Gerda Taro, travelled to Spain to cover the Civil War, which had erupted in July that year. It was in Spain that Capa took the photo, first published in September 1936 by French magazine Vu, and later in Life magazine, that made him a household name – The Falling Soldier, a photograph of a Republican soldier supposedly at the moment of death from a sniper’s bullet.

The photo has been the subject of much debate. While Capa’s defenders, particularly his brother, maintain its authenticity, others accuse Capa of having staged the scene. Research shows that the photograph was taken some 35 miles away from where Capa said it had been, in an area that saw no fighting on the day the shot was taken. Perhaps more damning is that the photo bears no evidence of a bullet wound.

On 25 July 1937, while Capa was away in Paris, Gerda Taro (pictured) was injured in Spain, crushed by a reversing Republican tank. She died the following day, a week short of her 27th birthday. Grief-stricken, Capa traveled to China to document the Sino-Japanese War.

On 25 July 1937, while Capa was away in Paris, Gerda Taro (pictured) was injured in Spain, crushed by a reversing Republican tank. She died the following day, a week short of her 27th birthday. Grief-stricken, Capa traveled to China to document the Sino-Japanese War.

With the outbreak of war in 1941, following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Capa was in New York and started working for various magazines, including Life and Time. Sent to Europe, he accompanied American troops during the 1943 advance through German-held Sicily, and, in October, the battle for Naples.

The ‘Magnificent Eleven’

In April 1944, he transferred to London ahead of the planned invasion of Normandy. He landed with the second wave of troops on Omaha Beach on 6 June, D-Day. Sheltering from German gunfire and shaking with fear ‘from toe to hair’, Capa managed, over the course of two hours, to take 106 shots of American soldiers fighting and struggling on the beach. He quickly returned to London to have the four rolls of film developed. Unfortunately, a laboratory assistant dried the pictures too quickly, thereby melting three rolls and half the fourth. The only surviving eleven photographs were, as a result of the blunder, blurred. Since dubbed the ‘Magnificent Eleven’, part of the set was originally published in Life on 11 June.

Following the war, Capa became an American citizen and, in 1947, founded Magnum Photos in Paris with French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson. He continued his travels, working in Israel and the Soviet Union, where he took photos for the novelist John Steinbeck on his tour of the country.

Although Capa had decided not to work in any more war zones, in 1954 he accepted Time’s request to cover the war in French Indochina, modern-day Vietnam. On 25 May, in the city of Thái Bình, Capa stepped on a mine and was killed. He was 40.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about WW2 in The Clever Teens’ Guide to World War Two (80 pages) available as ebook and paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.