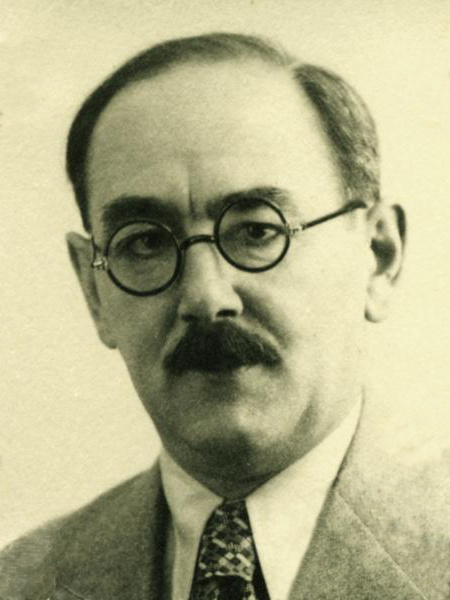

Imre Nagy is remembered with great affection in today’s Hungary. Although a communist leader during its years of one-party rule, Nagy was the voice of liberalism and reform, advocating national communism, free from the shackles of the Soviet Union. Following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Nagy was arrested, tried in secret, and executed. His rehabilitation and reburial in 1989 played a significant and symbolic role in ending communist rule in Hungary.

Imre Nagy was born 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in southern Hungary. He worked as a locksmith before joining the Austrian-Hungary army during the First World War. In 1915, he was captured and spent much of the war as a prisoner of war in Russia. He escaped and having converted to communism, joined the Red Army and fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Imre Nagy was born 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in southern Hungary. He worked as a locksmith before joining the Austrian-Hungary army during the First World War. In 1915, he was captured and spent much of the war as a prisoner of war in Russia. He escaped and having converted to communism, joined the Red Army and fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Agriculture

In 1918, Nagy returned to Hungary as a committed communist and served the short-lived Soviet Republic established by Bela Kun in Hungary. Following its collapse in August 1919, after only five months, Nagy, as with other former members of Kun’s regime, lived underground, liable to arrest. Eventually, in 1928, he fled to Austria and from there, in 1930, to the Soviet Union, where he spent the next fourteen years studying agriculture.

Following the Second World War, Nagy returned again to Hungary serving as Minister of Agriculture in Hungary’s post-war communist government. Loyal to Stalin, Nagy led the charge of collectivization, redistributing the land of landowners to the peasants.

Prime Minister

In July 1953, four months after Stalin’s death and with the Soviet Union’s approval, Nagy was appointed prime minister, replacing the unpopular and ruthless, Mátyás Rákosi (pictured). Rákosi, ‘Stalin’s Best Hungarian Disciple’, had been responsible for a reign of terror in which some 2,000 Hungarians were executed and up to 100,000 imprisoned. Nagy tried to usher in a move away from Moscow’s influence and introduce a period of liberalism and political and economic reform. This, as far as the Kremlin was concerned, was setting a bad example to other countries within the Eastern Bloc. Nagy quickly became too popular for the Kremlin’s liking and in April 1955 Rákosi was put back in charge and the terror and oppression started anew. Seven months later, Nagy was expelled from the communist party altogether.

In July 1953, four months after Stalin’s death and with the Soviet Union’s approval, Nagy was appointed prime minister, replacing the unpopular and ruthless, Mátyás Rákosi (pictured). Rákosi, ‘Stalin’s Best Hungarian Disciple’, had been responsible for a reign of terror in which some 2,000 Hungarians were executed and up to 100,000 imprisoned. Nagy tried to usher in a move away from Moscow’s influence and introduce a period of liberalism and political and economic reform. This, as far as the Kremlin was concerned, was setting a bad example to other countries within the Eastern Bloc. Nagy quickly became too popular for the Kremlin’s liking and in April 1955 Rákosi was put back in charge and the terror and oppression started anew. Seven months later, Nagy was expelled from the communist party altogether.

Hungarian Revolution

On 23 October 1956, the people of Hungary rose up against their government and its Soviet masters. The Hungarian Revolution had begun. Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow sent the tanks in to restore order while the rebels demanded the return of Imre Nagy. Khrushchev relented and Nagy was back in control, calling for calm and promising political reform, while, around him, the Soviets tanks tried to quash the uprising. On 28 October, Khrushchev withdrew the tanks, and for a few short days, the people of Hungary wondered whether they had won.

On 1 November, Nagy boldly announced his intentions: he promised to release political prisoners, including Cardinal Mindszenty (pictured), notoriously imprisoned by Rakosi’s regime; he promised to withdraw Hungary from the Warsaw Pact; that Hungary would become a neutral nation; and he promised open elections and an end to one-party rule. Two days later, he went so far as to announce members of a new coalition government, which included a number of non-communists. This was all too much for the Kremlin. If Nagy delivered on these reforms, what sort of message would it send to other members of the Eastern Bloc – its very foundation would be at risk?

On 1 November, Nagy boldly announced his intentions: he promised to release political prisoners, including Cardinal Mindszenty (pictured), notoriously imprisoned by Rakosi’s regime; he promised to withdraw Hungary from the Warsaw Pact; that Hungary would become a neutral nation; and he promised open elections and an end to one-party rule. Two days later, he went so far as to announce members of a new coalition government, which included a number of non-communists. This was all too much for the Kremlin. If Nagy delivered on these reforms, what sort of message would it send to other members of the Eastern Bloc – its very foundation would be at risk?

On 4 November, Khrushchev sent the tanks back in; this time in far greater numbers. Nagy appealed to the West. While the US condemned the Soviet attack as a ‘monstrous crime’, it did nothing, distracted by presidential elections; while Britain and France were in the midst of their own calamity, namely the Suez Crisis. Anyway, the West was never going to risk war for the sake of Hungary.

The Hungarian Uprising was crushed. Nagy was replaced by Janos Kadar, a man loyal to Moscow, and who would remain in charge of Hungary for the next 32 years, until ill health forced his retirement in May 1988.

Secret Trial

Nagy knew he was in danger and sought refuge in the Yugoslavian Embassy in Budapest. Despite receiving a written assurance from Kadar guaranteeing him safe passage out of Hungary, on 22 November 1956, Nagy, along with others, was kidnapped by Soviet agents as he tried to leave the embassy. He was smuggled out of the country and taken to Romania.

Two years later, Nagy was secreted back into Hungary and along with his immediate colleagues, put on trial. The trial, which lasted from 9 to 15 June, was tape-recorded in its entirety – 52 hours. Charged with high treason and of attempting to overthrow the supposedly legally-recognised Hungarian government, Nagy was found guilty and sentenced to death.

On 16 June 1958, Imre Nagy was hanged; his body dumped, face down, in an unmarked grave. He was 62.

1989

Exactly thirty-one years later, on 16 June 1989, Imre Nagy and his colleagues were rehabilitated, reinterred, and afforded a public funeral. The whole of the country observed a minute’s silence. Six coffins were placed on the steps of the Exhibition Hall in Budapest’s Heroes Square. One coffin was empty – representative of all revolutionaries that had fallen in ’56.

Exactly thirty-one years later, on 16 June 1989, Imre Nagy and his colleagues were rehabilitated, reinterred, and afforded a public funeral. The whole of the country observed a minute’s silence. Six coffins were placed on the steps of the Exhibition Hall in Budapest’s Heroes Square. One coffin was empty – representative of all revolutionaries that had fallen in ’56.

It was an emotional and symbolic event attended by over 100,000 people. The writing was on the wall for Hungary’s communist rulers. Sure enough, on the 33rd anniversary of the start of the revolution, 23 October 1989, the People’s Republic of Hungary was replaced by the Republic of Hungary with a provisional parliamentary president in place. The road to democracy was swift – parliamentary elections were held in Hungary on 24 March 1990, the first free elections to be held in the country since 1945. The totalitarian government was finished – Hungary, at last, was free.

Meanwhile, on 6 July 1989, the Hungarian judicial acquitted Imre Nagy of high treason. The very same day, Janos Kadar died.

Rupert Colley

Rupert Colley

Read more about the revolution in The Hungarian Revolution, 1956, available as ebook and paperback (124 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.