Most leaders possess a strength of character, charisma even, for which they are either admired or disliked, loved or loathed, but always acknowledged. Walter Ulbricht, East Germany’s head of state from 1950 to 1973, was an unusually dull man, devoid of personality, devoted to the socialist cause, but with no empathy for the working masses, the very people he was supposedly fighting for.

Early Days

Born 30 June 1893 in Leipzig, Walter Ulbricht left school after only eight years and became a cabinet maker. Joining the German army in 1915, during the First World War, Walter Ulbricht served in both the Balkans and the Eastern Front but deserted towards the end of the war. Imprisoned in Belgium, he was released during the chaotic days of the German Revolution.

Born 30 June 1893 in Leipzig, Walter Ulbricht left school after only eight years and became a cabinet maker. Joining the German army in 1915, during the First World War, Walter Ulbricht served in both the Balkans and the Eastern Front but deserted towards the end of the war. Imprisoned in Belgium, he was released during the chaotic days of the German Revolution.

In 1920, he became a member of the German Communist Party, the KDP, and quickly rose through its ranks. He studied in the Soviet Union at the International Lenin School, a secretive school in Moscow that taught foreign communists how to be perfect Leninists and Marxists. In 1928, back in Germany, Ulbricht was elected into the Reichstag. It was a time of violent clashes between the communists and Nazis. Once Hitler assumed power as chancellor in January 1933, opposition parties were soon outlawed by his Enabling Act, and communists all over Germany fled or went into hiding. Ulbricht was one of them – fleeing first to France and Czechoslovakia, and then Spain during the Civil War of 1936-39 where he sided with the republicans in the International Brigades. He later received a medal for his time in Spain, angering fellow recipients, as Ulbricht never saw active service, preferring instead to hunt out Trotskyites and other unreliable elements within the KDP.

He returned to Moscow in 1937, and actively supported Stalin’s show trials and purges. Ulbricht watched as many of his superiors were purged, allowing him to rise further up the KDP ladder. It was almost as if his blandness helped him survive while his more charismatic colleagues fell. As a non-entity, no one really noticed Walter Ulbricht. He remained in Russia during the war and was let loose on German prisoners of war in order to ‘convert’ them to communism.

East German Uprising

On 30 April 1945, the day Hitler committed suicide, Ulbricht returned to Germany and within five years had manoeuvred himself into power as General Secretary, effectively head of state of the newly-formed East Germany, or the German Democratic Republic (the DDR, to use its German initials).

Not unlike the power enjoyed by Mátyás Rákosi in Hungary, Ulbricht’s position was secure while Stalin was alive. Stalin died on 5 March 1953, and, sure enough, within four months, Rakosi had been removed from power. Meanwhile, Ulbricht faced his first real test as leader when, in June 1953, East German workers went on strike. But with the help of Soviet tanks, Ulbricht quashed the East German Uprising and survived.

In 1955, Ulbricht committed East Germany to the Warsaw Pact.

No one has any intention of building a wall

By the early 1960s the difference between West and East Berlin had become marked; the former enjoying prosperity and freedom that made the latter seem drab in comparison. The huge migration from East to West Berlin, and then into West Germany, was a great advertisement for capitalism and an equally poor one for communism and for Ulbricht and the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev. But proposals for a wall in Berlin to stem the flow were firmly rejected by Moscow – it would only highlight their failure. Better to win the hearts of the East Berliners. But by 1961 almost 3 million, mainly young, East Germans had gone West, a whole sixth of the population, from communism to capitalism in minutes, causing severe labour shortages and an acute embarrassment for the socialist utopia. Their hearts had not been won.

On 15 June 1961, only two months before the Berlin Wall was erected, Ulbricht, at a press conference, said, ‘The builders of our capital are fully engaged in residential construction, and its labour force is deployed for that’; finishing with the now-infamous remark: ‘No one has any intention of building a wall‘. But, with now 1,700 going west every day, of course, they did. On the night of 12‒13 August 1961, a barbed-wire fence was erected. As the wire went up, many East Germans made a last-minute dash for freedom among scenes of high tension. Days later, a concrete wall completely encircled the 103-mile perimeter of West Berlin. The most potent symbol of the Cold War was in place and was to remain so for 28 years.

Retirement

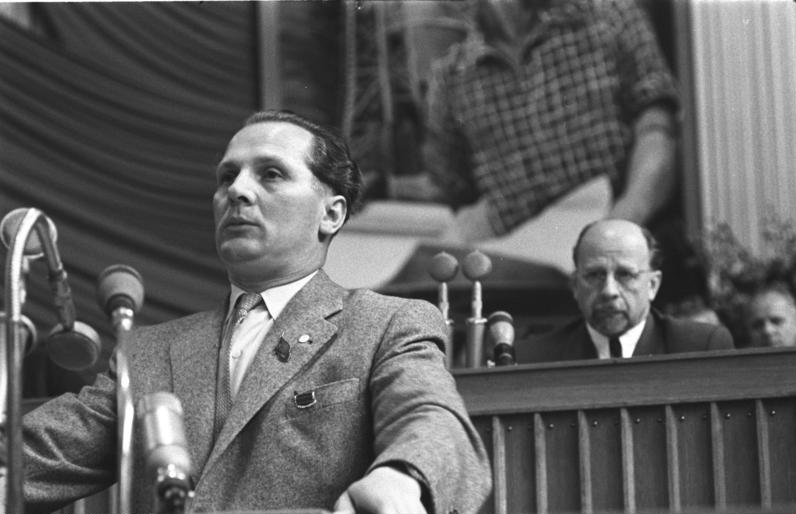

The late 1960s saw a gentle improvement in relations between the Soviet Union and West Germany, and their respective leaders, Leonid Brezhnev and Willy Brandt. But Ulbricht remained firmly anti-West Germany, and the Soviet politburo deemed him out of step. On 3 May 1971, Ulbricht resigned on the grounds of ill health. He was succeeded by Erich Honecker who remained in power until October 1989, just three weeks before the fall of the Berlin Wall. (Pictured is Honecker speaking in 1958, with the attentive and beady-eyed Ulbricht behind him, watching). Ulbricht retained various honorary positions, including head of state, until his death, aged 80, on 1 August 1973.

The late 1960s saw a gentle improvement in relations between the Soviet Union and West Germany, and their respective leaders, Leonid Brezhnev and Willy Brandt. But Ulbricht remained firmly anti-West Germany, and the Soviet politburo deemed him out of step. On 3 May 1971, Ulbricht resigned on the grounds of ill health. He was succeeded by Erich Honecker who remained in power until October 1989, just three weeks before the fall of the Berlin Wall. (Pictured is Honecker speaking in 1958, with the attentive and beady-eyed Ulbricht behind him, watching). Ulbricht retained various honorary positions, including head of state, until his death, aged 80, on 1 August 1973.

The greatest idiot

Like any communist leader, a cult of personality was built around Walter Ulbricht. Parades and celebrations, such an intrinsic part of life under communism, would include banners and flags bearing his portrait. Every office and every home would have a framed picture of him. If they didn’t – then why not?

Wherever he went, he would be greeted with standing ovations; children would present him with bunches of flowers. Yet, for all this hyerbole, no one really liked Walter Ulbricht. Elfriede Brüning, an East German novelist, wrote that he was incapable of exchanging a pleasant word. Even Laventry Beria, Stalin’s notorious head of his secret police, described Ulbricht as the ‘greatest idiot’ that he had ever met. And Alexander Dubcek, Czechoslovakian leader during the 1968 Prague Spring, called Ulbricht, ‘a dogmatist fossilized somewhere in Stalin’s period;’ adding, ‘I found him personally repugnant.’ Ulbricht even fell out with his stepdaughter to the point of disinheriting her.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the Cold War in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Cold War (75 pages) available as paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.