In August 1942, Winston Churchill, Great Britain’s wartime prime minister, flew to Moscow and there met for the first time the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin. Fourteen months before, on 22 June 1941, Hitler had launched Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, the largest military invasion ever conducted. Almost immediately, Stalin was urging Churchill to open a second front by attacking Nazi-occupied Europe from the West, thereby forcing Hitler to divert troops to the west and alleviating in part the enormous pressure the Soviet Union found itself under. Now, as Churchill prepared to meet Stalin, German forces were bearing down on the strategically and symbolically important Russian city of Stalingrad.

Churchill knew that if Germany were to defeat the Soviet Union then Hitler would be able to concentrate his whole military strength on the west. But although tentative plans for a large-scale invasion were afoot, to act too quickly, too hastily, would be foolhardy. Churchill withstood Stalin’s pressure. There would be no second front for at least another year. But, in the meanwhile, Churchill was able to offer a ‘reconnaissance in force’ on the French port of Dieppe, with the objective of drawing away German troops from the Eastern Front. Whether Stalin was at all appeased by this morsel of compensation, Churchill does not say.

Operation Jubilee

Thus, in the early hours of 19 August 1942, the Allies launched Operation Jubilee – the raid on Dieppe, 65 miles across from England. 252 ships crossed the Channel in a five-pronged attack carrying tanks together with 5,000 Canadians and 1,000 British and American troops plus a handful of fighters from the French resistance. Nearing their destination, one prong ran into a German merchant convoy. A skirmish ensued. More fatally, it meant that the element of surprise had been lost – aware of what was taking place, the Germans at Dieppe were now waiting in great numbers.

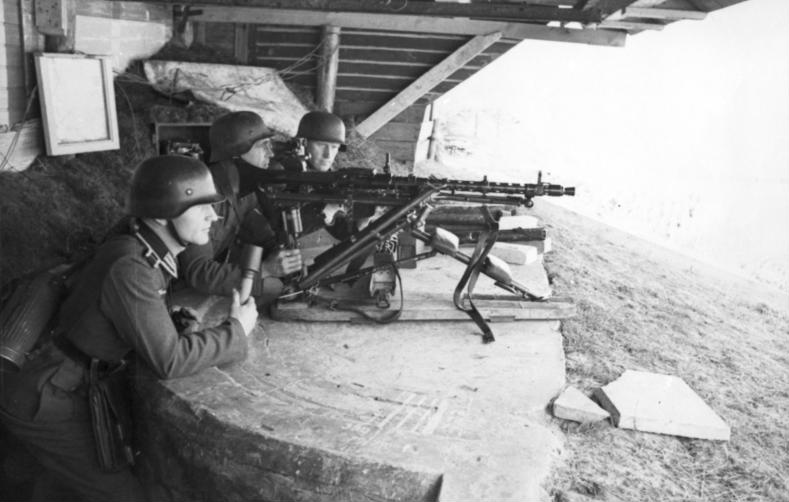

Pictured: German soldiers defending the French port of Dieppe against the Anglo-Canadian raid, 19 August 1942.

Pictured: German soldiers defending the French port of Dieppe against the Anglo-Canadian raid, 19 August 1942.

What followed was a disaster as the Germans unleashed a withering fire from cliff tops and port-side hotels. A Canadian war correspondent described the scene as men tried to disembark from their landing craft: the soldiers ‘plunged into about two feet of water and machine-gun bullets laced into them. Bodies piled up on the ramp.’ Neutralised by German fighters, support overhead from squadrons of RAF planes proved ineffectual. Only 29 tanks managed to make it ashore where they struggled on the shingle beach, and of those only 15 were able to advance as far as the sea wall only to be prevented from encroaching into the town by concrete barriers.

The Dieppe Raid, which had lasted just six hours, was a costly affair – 60 per cent of ground troops were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The operation left 1,027 dead, of whom 907 were Canadian. A further 2,340 troops were captured, and 106 aircraft shot down. An American, Lieutenant Edward V Loustalot, earned the unenviable distinction of becoming the first US soldier killed in wartime Europe.

Lessons learned

Despite the failure of Dieppe and the high rate of losses, important lessons were learned – that a direct assault on a well-defended harbour was not an option for any future attack; and that superiority of the air was a prerequisite. Churchill concluded that the raid had provided a ‘mine of experience’.

Despite the failure of Dieppe and the high rate of losses, important lessons were learned – that a direct assault on a well-defended harbour was not an option for any future attack; and that superiority of the air was a prerequisite. Churchill concluded that the raid had provided a ‘mine of experience’.

In charge of the operation, Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, cousin to King George VI, would later say, ‘If I had the same decision to make again, I would do as I did before … For every soldier who died at Dieppe, ten were saved on D-Day.’ Hitler too felt as if a lesson had been learned. Knowing that at some point the Allies would try again, he said, ‘We must reckon with a totally different mode of attack and in quite a different place’.

Pictured: Canadian prisoners of war being lead through Dieppe by German soldiers.

The attack would come almost two years later – 6 June 1944.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.