The date is 8 November 1939, the location – the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall in Munich. With their uniforms freshly pressed, their buttons gleaming, their shoes polished, Hitler’s longest-standing comrades filed into the hall, their chests puffed up with pride, their wives at their sides. This event, on this day, had become an annual occasion in the Nazi calendar, a ritual of celebration and remembrance. The climax of the evening, awaited with great anticipation, would be Hitler’s appearance and his speech in which he would praise and pour tribute on these self-satisfied men, his old-timers.

But there was one man who awaited Hitler’s appearance with equal anticipation – but for entirely different reasons. This man was a 36-year-old carpenter, Johann Georg Elser, born 4 January 1903. For Elser, a long-time anti-Nazi, had planted a bomb with the full intention of killing Adolf Hitler. And his bomb was due to explode halfway through the Fuhrer’s speech.

Kill Hitler

Georg Elser had always been quietly defiant in his hatred of the Nazi regime – he’d supported the communists and, once Hitler was in power, refused to give the Nazi salute. He feared Hitler’s aggressive warmongering and foresaw the coming of war and resolved himself, in his own way, to do something to prevent it – and that was to kill Hitler.

Georg Elser had always been quietly defiant in his hatred of the Nazi regime – he’d supported the communists and, once Hitler was in power, refused to give the Nazi salute. He feared Hitler’s aggressive warmongering and foresaw the coming of war and resolved himself, in his own way, to do something to prevent it – and that was to kill Hitler.

Exactly a year earlier before the fateful night, on the 8 November 1938, Elser attended the same annual commemoration in Munich marking the anniversary of Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. And it was this annual event, he decided, that would provide the perfect opportunity to implement his audacious plan. The following night, he witnessed first-hand the vicious Kristallnacht, when Nazis throughout the country terrorized Germany’s Jews in a concentrated orgy of killing and violence. Seeing for himself this state-sponsored anarchy merely confirmed for Elser that what he was doing was right.

Elser spent the next year preparing. Each year on 8 November, since 1933, Hitler had come to the same beer hall and delivered a two-hour speech, starting at 8.30, the precise time that, in 1923, he had bulldozed into the hall brandishing a pistol, interrupting a meeting of Bavarian city officials and, firing two shots into the ceiling, declared revolution. The Beer Hall Putsch failed but had become an occasion to honour and remember the Nazis that had fallen that night in Munich.

then, in 1938, at the height of Stalin’s purges, Bystrolyotov was arrested by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. Tortured and crippled, and made to ‘confess’ to fantastical charges, he was sentenced to 20 years of hard

then, in 1938, at the height of Stalin’s purges, Bystrolyotov was arrested by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. Tortured and crippled, and made to ‘confess’ to fantastical charges, he was sentenced to 20 years of hard  Born 7 June 1837, Alois Schicklgruber was the son of a 42-year-old unmarried

Born 7 June 1837, Alois Schicklgruber was the son of a 42-year-old unmarried  Despairing, Yusupov shot Rasputin in the back and then, satisfied, left to join his fellow conspirators. Returning a little later to check on the body, Rasputin sat up and lunged at the prince. The prince’s friends came to his rescue, shooting the ‘mad monk’ a further three times, once in the forehead. But still refusing to die, Rasputin’s attackers resorted to clubbing him senseless then wrapping his body in a blue rug and throwing him in the icy waters of the River Neva.

Despairing, Yusupov shot Rasputin in the back and then, satisfied, left to join his fellow conspirators. Returning a little later to check on the body, Rasputin sat up and lunged at the prince. The prince’s friends came to his rescue, shooting the ‘mad monk’ a further three times, once in the forehead. But still refusing to die, Rasputin’s attackers resorted to clubbing him senseless then wrapping his body in a blue rug and throwing him in the icy waters of the River Neva.

Born in Tokyo on 30 December 1884, Hideki Tojo, the son of a general, was brought up in a military environment that held little regard for politicians or civilians. An admirer of Adolf Hitler, Tojo advocated closer ties between Japan and Germany and Italy, and in September 1940, the three Axis powers signed the Tripartite Pact.

Born in Tokyo on 30 December 1884, Hideki Tojo, the son of a general, was brought up in a military environment that held little regard for politicians or civilians. An admirer of Adolf Hitler, Tojo advocated closer ties between Japan and Germany and Italy, and in September 1940, the three Axis powers signed the Tripartite Pact. A lover of Rachmaninov’s music and a cuddly uncle-figure to Svetlana Alliluyeva, pictured, Beria had his bodyguards abduct young girls off the streets for his devious sexual pleasure. Those that refused his predatory advances risked being packed off to a gulag.

A lover of Rachmaninov’s music and a cuddly uncle-figure to Svetlana Alliluyeva, pictured, Beria had his bodyguards abduct young girls off the streets for his devious sexual pleasure. Those that refused his predatory advances risked being packed off to a gulag. The Emperor of the Austrian-Hungarian (Habsburg) Empire, Franz Joseph, had ruled since 1848, and was to do so until his death in 1916, aged 86, a rule of 68 years. When his nephew and heir presumptive, Archduke Franz Ferdinand announced his desire to marry Sophie Chotek it sent shockwaves through the royal family. For Sophie,

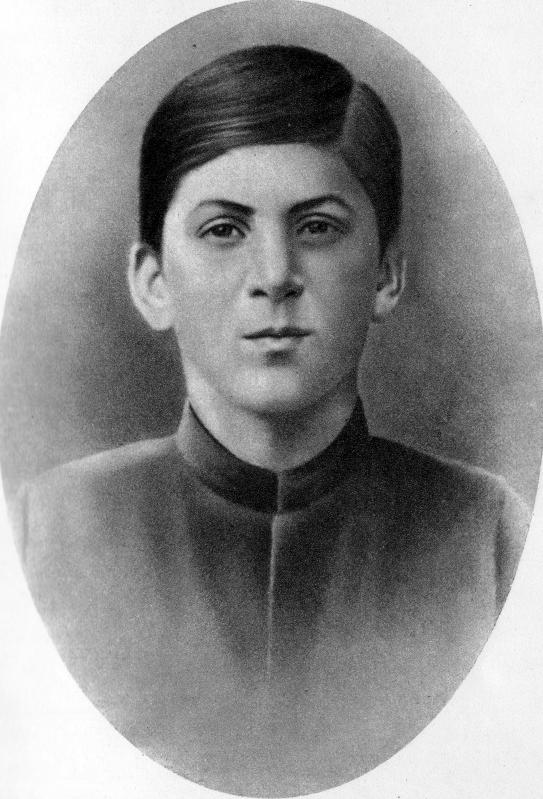

The Emperor of the Austrian-Hungarian (Habsburg) Empire, Franz Joseph, had ruled since 1848, and was to do so until his death in 1916, aged 86, a rule of 68 years. When his nephew and heir presumptive, Archduke Franz Ferdinand announced his desire to marry Sophie Chotek it sent shockwaves through the royal family. For Sophie,  Joseph Stalin’s father, Vissarion Dzhugashvili, known as Basu, was a shoemaker. An alcoholic, he spent much of his time in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, 50 miles east of Gori) producing shoes for the Russian army. On his drunken and increasingly rare appearances at home, he would beat his wife and son. (Pictured is Stalin, aged 15, in 1894).

Joseph Stalin’s father, Vissarion Dzhugashvili, known as Basu, was a shoemaker. An alcoholic, he spent much of his time in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, 50 miles east of Gori) producing shoes for the Russian army. On his drunken and increasingly rare appearances at home, he would beat his wife and son. (Pictured is Stalin, aged 15, in 1894). The Allies knew there was a build-up of German troops and equipment around the Ardennes but never believed Hitler was capable of such a bold initiative. Only the day before the attack, the British commander,

The Allies knew there was a build-up of German troops and equipment around the Ardennes but never believed Hitler was capable of such a bold initiative. Only the day before the attack, the British commander,