6 December 1956 saw one of the most violent and politically-charged sporting clashes in history, an event that came to be known as ‘ Blood in the Water ’. The occasion was the Olympic water polo semi-final between Hungary and the USSR. Played against the backdrop of Cold War politics, the game was, from start to finish, fraught with tension.

Water Polo

Hungary was the undoubted superpower of 1950s water polo. They had won gold at three of the four previous Olympic Games, and silver at the London Olympics of 1948; and were firm favourites to triumph again at the Melbourne Olympics of 1956, the first Olympics to be held in the southern hemisphere. The Soviets, jealous of Hungary’s success in the water, had been training in Hungary in the months leading up to the Olympics, trying to learn what made the Hungarians so good at their game. Since 1949, Hungary had been a Soviet satellite and thus the Soviet team arrived, uninvited, and made use of Hungary’s pool facilities and expertise. A ‘friendly’ match in Moscow earlier in the year had erupted in violence; the Russians having won thanks to some dubious partisan referring.

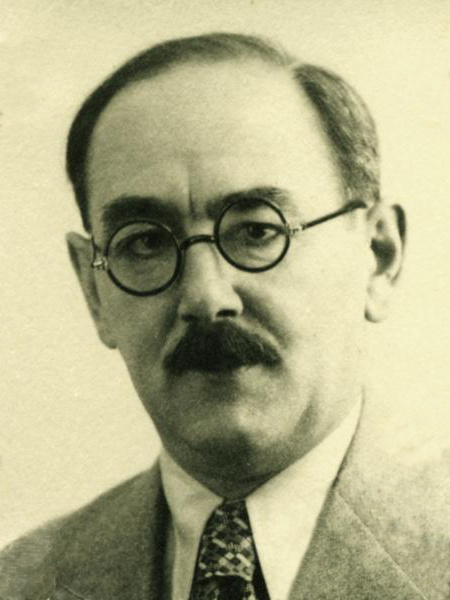

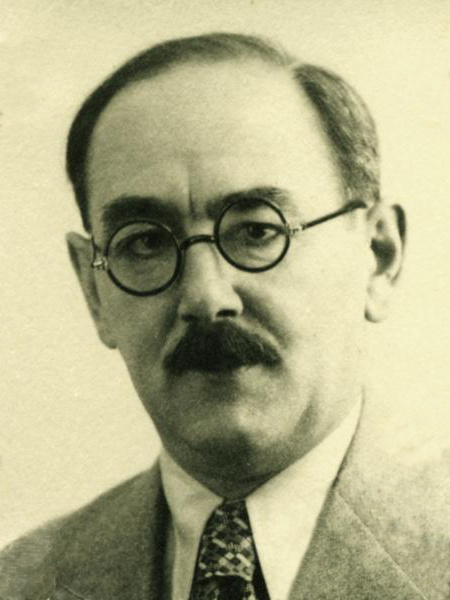

Then, in October 1956, came the

Hungarian Revolution. The people of Hungary stood up to the oppression of a tyrannical and foreign ruler. The Soviet leader,

Nikita Khrushchev, sent in the tanks to quell the uprising and restore order. The tanks, having failed, were withdrawn. Khrushchev replaced Hungary’s hard-line communist rulers with the more populist

Imre Nagy (pictured). Nagy announced his decision to withdraw Hungary from the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact, introduce much-needed reform and, most alarmingly for Khrushchev, spoke of independence.

A week later, the Soviet tanks re-appeared and, this time, with brutal efficiency, crushed the revolution. Some 3,000 Hungarian citizens were killed. Nagy took sanctuary in the Yugoslav embassy but, a year later, having been lured out, was arrested by the new pro-Soviet regime in Budapest, tried and executed.

Meanwhile, while the Hungarian Revolution played out, the national Olympic water polo team had been holed up with Russian minders in a hillside hotel in Budapest within earshot of the gun battles raging below. On 1 November they started on their three-week journey to Melbourne not knowing the outcome of the uprising. It was only when they arrived in Australia, that they learnt that their oppressive rulers were back in charge (and would remain so for another 33 years). It was at this point that many of the players decided that, once the Olympics were over, they would not be returning to their homeland.

They won their first four games of the tournament against Great Britain, the USA, Italy and Germany. And so they reached the semi-final to face the team that represented their oppressors. The scene was set for a tumultuous confrontation – blood in the water.

Blood in the Water

The game took place on 6 December. The Hungarian team had decided from the off to conduct a psychological battle by needling their opponents. Having been forced to learn the Russian language two hours a day throughout their school years, the Hungarian players could easily make themselves understood as they mocked their opponents’ illegitimacy. Within the first minute of the heavily-charged grudge match, the referee had consigned a Russian player to the penalty box.

Fights continued throughout the game, both above and below the water line. Together with their method of zonal marking, a revolutionary tactic for the time, the Hungarians had the Soviets quickly ruffled.

The Australian crowd’s sympathy clearly lay with the Hungarians, chanting ‘Go Hungary’ throughout the game and waving the Hungarian flag with the Soviet emblem ripped from its centre. (The Australian team had been beaten by the USSR earlier in the tournament).

With the match drawing to its close, the score was 4-0 to Hungary. In the last couple of minutes, Hungary’s star player, the 21-year-old Ervin Zador, was assigned by his captain to mark the Soviet forward, Valentin Prokopov. Zador had already scored two of Hungary’s goals. On hearing the referee blow his whistle, Zador made what he called a ‘horrible mistake’, and momentarily took his eye off the Soviet. He looked back to see Prokopov’s arm windmilling before being thumped a mighty blow that caught him in the eye and cheek. There was, indeed, blood in the water.

The Australian crowd went berserk and surged forward. The police, who had been told to expect trouble, hence their presence

at the game, stepped in. The referee blew full time a minute early while the police escorted the Soviet team away from the baying crowd. Ervin Zador was led from the pool with blood pouring from his face. A

photograph of the bloodied player has become an iconic image of Cold War-era Olympics.

Thus, having won, the Hungarian team advanced to the final against Yugoslavia. Zedor, although desperate the play, was unable to – his eye was too swollen. He nervously watched the game from the stands as his teammates triumphed, winning the final 2-1. He received his gold medal on the podium dressed in a suit. (The Soviets won their play-off match, beating Germany 6 -4, and hence earned the bronze medal).

San Francisco

Following the Olympics, Zador, along with half his teammates, sought asylum. It was, he said years later, a difficult decision – he was at the peak of his career and could look forward to a bright sporting future in Hungary. But the Soviet oppression was too much. Thus, he moved to the US and settled in San Francisco. Water polo in the US was not the sport it was in Hungary and, reluctantly, Zedor gave it up. Instead, he took up a job as a swimming instructor and trained a young Mark Spitz, who, at the Munich Olympics of 1972, won seven gold medals.

2006, the fiftieth anniversary of the Blood in the Water game, saw two cinematic releases based on the event – a documentary,

Freedom’s Fury, executively produced by Quentin Tarantino, no less, and narrated by Zedor’s former protégé, Mark Spitz; and an excellent Hungarian feature film,

Children of Glory.

Ervin Zador died 28 April 2012.

Rupert Colley

Rupert Colley

Read more about the Hungarian Revolution in The Hungarian Revolution, 1956 (126 pages) available as ebook and paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, Apple Books and other stores.

Like this:

Like Loading...

On 14 December 1861, Albert, the Prince Consort, died. He was only 42. His unexpected death plunged Queen Victoria into grief so overwhelming that it endured for the rest of her life. Her pain was shared by the nation in an outpouring of angst that would not be seen again until the death, 136 years later, of Princess Diana. But after a while, the public and politicians alike began to ask whether the Queen’s period of mourning would ever end.

On 14 December 1861, Albert, the Prince Consort, died. He was only 42. His unexpected death plunged Queen Victoria into grief so overwhelming that it endured for the rest of her life. Her pain was shared by the nation in an outpouring of angst that would not be seen again until the death, 136 years later, of Princess Diana. But after a while, the public and politicians alike began to ask whether the Queen’s period of mourning would ever end. In Britain or the US, we may consider the war to have started in 1939 or 1941, but many modern historians consider this to be too Eurocentric and that the war had really started in 1937 with the outbreak of hostilities between China and Japan. (Pictured is the Eternal flame at the Nanjing massacre memorial).

In Britain or the US, we may consider the war to have started in 1939 or 1941, but many modern historians consider this to be too Eurocentric and that the war had really started in 1937 with the outbreak of hostilities between China and Japan. (Pictured is the Eternal flame at the Nanjing massacre memorial).

The US may have been expecting

The US may have been expecting  On 17 October 1941, the prospect of war became more real – Japan’s prime minister, Fumimaro Konoye, known for his restraint and sense of compromise,

On 17 October 1941, the prospect of war became more real – Japan’s prime minister, Fumimaro Konoye, known for his restraint and sense of compromise,

Then, in October 1956, came the

Then, in October 1956, came the  Rupert Colley

Rupert Colley Together they had a son,

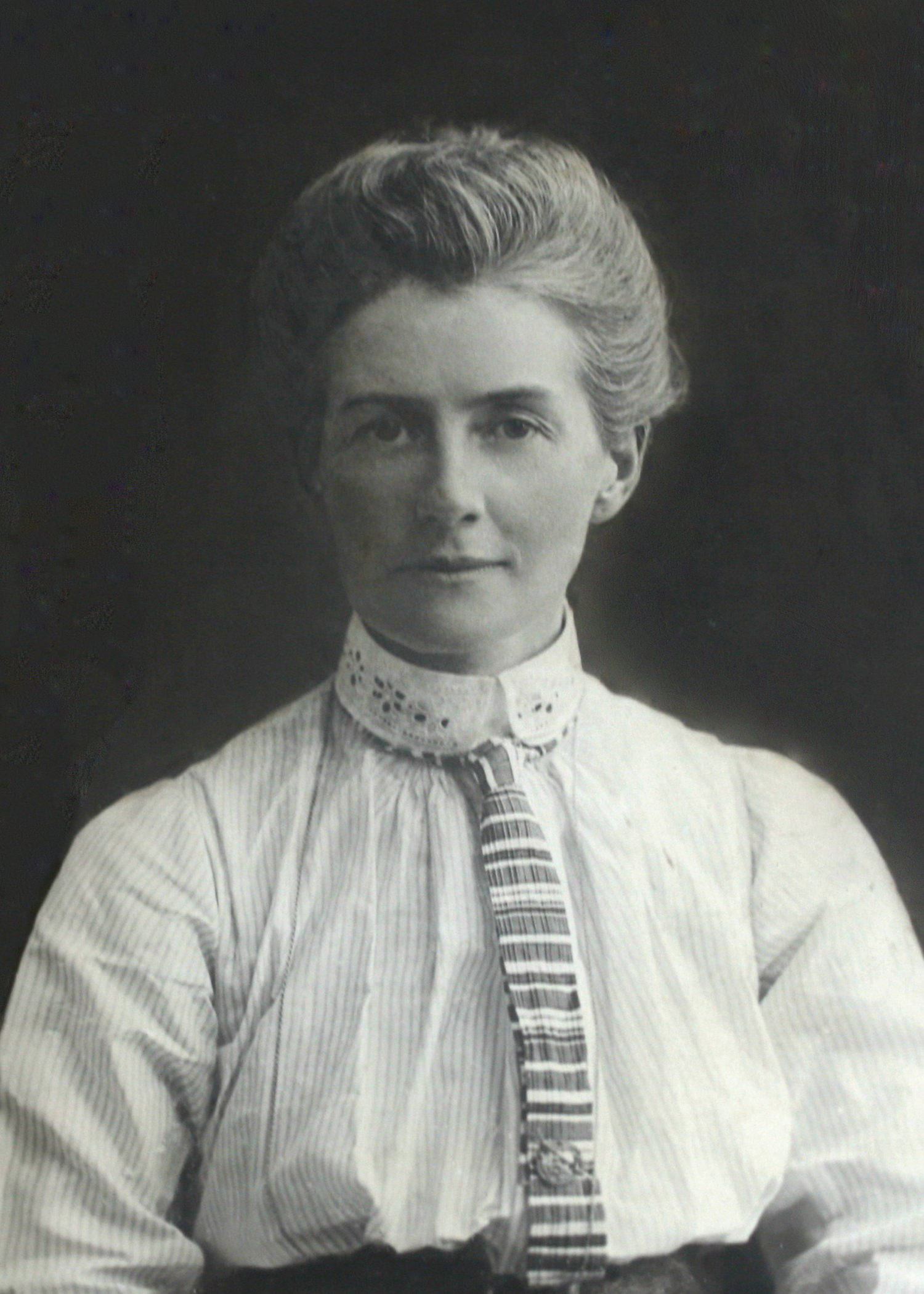

Together they had a son,  Following the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell refused the German offer of safe conduct into neutral Netherlands. She continued her work and in the process hid

Following the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell refused the German offer of safe conduct into neutral Netherlands. She continued her work and in the process hid  Mussolini ordered the destruction of the marriage records between him and his first wife, and stopped paying her maintenance, as previously ordered by the courts.

Mussolini ordered the destruction of the marriage records between him and his first wife, and stopped paying her maintenance, as previously ordered by the courts. 2. Parks was a lifelong believer in self-defense.

2. Parks was a lifelong believer in self-defense.