In August 1942, Winston Churchill, Great Britain’s wartime prime minister, flew to Moscow and there met for the first time the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin. Fourteen months before, on 22 June 1941, Hitler had launched Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, the largest military invasion ever conducted. Almost immediately, Stalin was urging Churchill to open a second front by attacking Nazi-occupied Europe from the West, thereby forcing Hitler to divert troops to the west and alleviating in part the enormous pressure the Soviet Union found itself under. Now, as Churchill prepared to meet Stalin, German forces were bearing down on the strategically and symbolically important Russian city of Stalingrad.

Churchill knew that if Germany were to defeat the Soviet Union then Hitler would be able to concentrate his whole military strength on the west. But although tentative plans for a large-scale invasion were afoot, to act too quickly, too hastily, would be foolhardy. Churchill withstood Stalin’s pressure. There would be no second front for at least another year. But, in the meanwhile, Churchill was able to offer a ‘reconnaissance in force’ on the French port of Dieppe, with the objective of drawing away German troops from the Eastern Front. Whether Stalin was at all appeased by this morsel of compensation, Churchill does not say.

Operation Jubilee

Thus, in the early hours of 19 August 1942, the Allies launched Operation Jubilee – the raid on Dieppe, 65 miles across from England. 252 ships crossed the Channel in a five-pronged attack carrying tanks together with 5,000 Canadians and 1,000 British and American troops plus a handful of fighters from the French resistance. Nearing their destination, one prong ran into a German merchant convoy. A skirmish ensued. More fatally, it meant that the element of surprise had been lost – aware of what was taking place, the Germans at Dieppe were now waiting in great numbers.

Pictured: German soldiers defending the French port of Dieppe against the Anglo-Canadian raid, 19 August 1942.

Pictured: German soldiers defending the French port of Dieppe against the Anglo-Canadian raid, 19 August 1942.

What followed was a disaster as the Germans unleashed a withering fire from cliff tops and port-side hotels. A Canadian war correspondent described the scene as men tried to disembark from their landing craft: the soldiers ‘plunged into about two feet of water and machine-gun bullets laced into them. Bodies piled up on the ramp.’ Neutralised by German fighters, support overhead from squadrons of RAF planes proved ineffectual. Only 29 tanks managed to make it ashore where they struggled on the shingle beach, and of those only 15 were able to advance as far as the sea wall only to be prevented from encroaching into the town by concrete barriers.

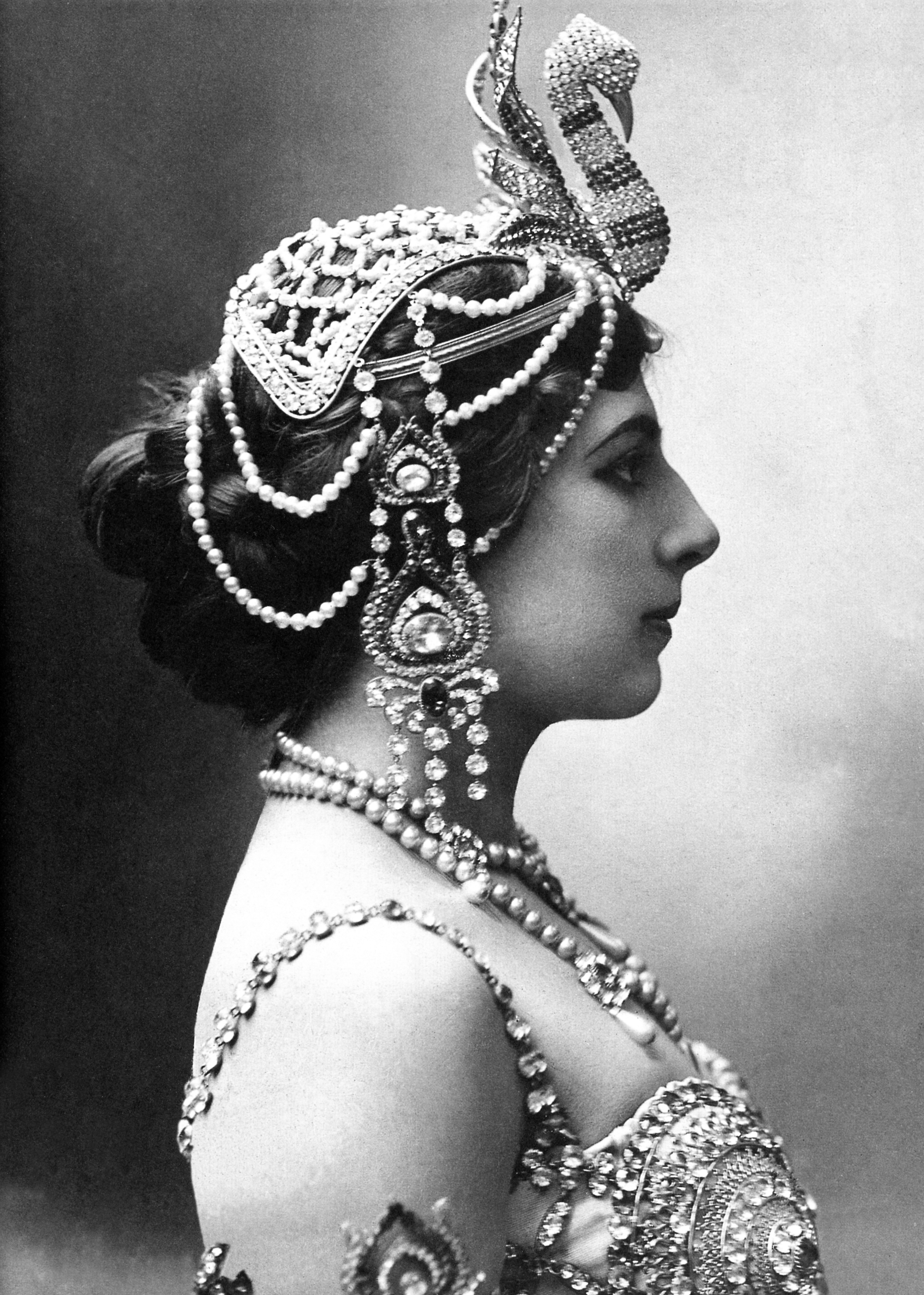

Born 7 August 1876 to a wealthy Dutch family, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married within three months of meeting each other and in 1895 moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children.

Born 7 August 1876 to a wealthy Dutch family, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married within three months of meeting each other and in 1895 moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children. Returning to Paris,

Returning to Paris,  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. In 1907, Hitler moved to Vienna while August Kubizek remained in Linz to work as an apprentice

In 1907, Hitler moved to Vienna while August Kubizek remained in Linz to work as an apprentice

Read more about the Cold War in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Cold War (75 pages) available as paperback and ebook from

Read more about the Cold War in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Cold War (75 pages) available as paperback and ebook from

A fervent supporter of Hitler, 36-year-old Count Claus von Stauffenberg had fought bravely during the Second World War for the Fuhrer. Fighting in Tunisia in 1943, Stauffenberg was badly wounded, losing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers of his left. Once recovered, Stauffenberg was transferred to the Eastern Front where he witnessed the atrocities firsthand which made him question his loyalty. As it became increasingly apparent that Germany would not win the war, Stauffenberg lost faith in Hitler and the Nazi cause.

A fervent supporter of Hitler, 36-year-old Count Claus von Stauffenberg had fought bravely during the Second World War for the Fuhrer. Fighting in Tunisia in 1943, Stauffenberg was badly wounded, losing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers of his left. Once recovered, Stauffenberg was transferred to the Eastern Front where he witnessed the atrocities firsthand which made him question his loyalty. As it became increasingly apparent that Germany would not win the war, Stauffenberg lost faith in Hitler and the Nazi cause. The earlier chapters concern Hitler’s upbringing, his formative years in Linz, Vienna, and Munich, his desire to be an

The earlier chapters concern Hitler’s upbringing, his formative years in Linz, Vienna, and Munich, his desire to be an

Born 18 July 1887, Vidkun Quisling’s life and early career had started promisingly. As a child, the son of a Lutheran pastor, he was considered somewhat a mathematical child prodigy and, as a young cadet coming out of military school, he gained the highest recorded marks in Norway.

Born 18 July 1887, Vidkun Quisling’s life and early career had started promisingly. As a child, the son of a Lutheran pastor, he was considered somewhat a mathematical child prodigy and, as a young cadet coming out of military school, he gained the highest recorded marks in Norway. With no support and no influence, Quisling looked destined to wither away into obscurity. But in Adolf Hitler, whom Quisling visited in December 1939, he had a friend.

With no support and no influence, Quisling looked destined to wither away into obscurity. But in Adolf Hitler, whom Quisling visited in December 1939, he had a friend.

Vera

Vera  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. Much of India, at the time, was governed by the East India Company. The monolithic,

Much of India, at the time, was governed by the East India Company. The monolithic,  The British took refuge on the fort’s ramparts. One soldier escaped, took to his horse and galloped the sixteen miles to the garrison based

The British took refuge on the fort’s ramparts. One soldier escaped, took to his horse and galloped the sixteen miles to the garrison based