The East German Uprising, 16-17 June 1953. Stalin had died three months before, and a new post-Stalinist era beckoned for those trapped behind the Iron Curtain. But if the workers of East Germany thought that Stalin’s death meant change, they were soon disabused as the East German premier, Walter Ulbricht, strove to increase industrial output.

Walter Ulbricht’s plan

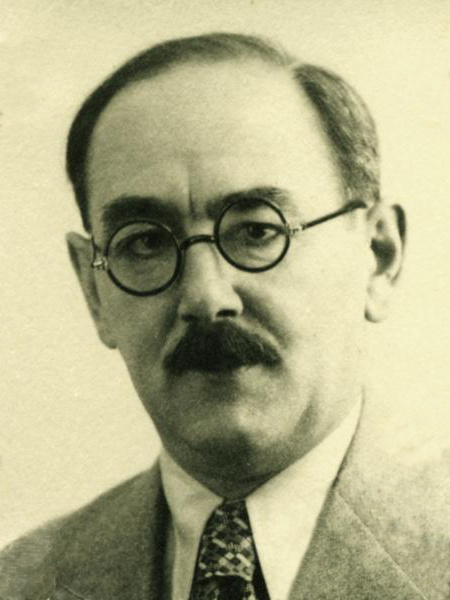

East Germany’s economy was stagnating and Ulbricht (pictured), a Stalinist to the core, proposed a range of measures to pump up the economy – increase taxes, increase prices and increase production by 10% – but with no corresponding increase in wages. If the new quotas were not met, workers were told, wages would be cut by a third. The Kremlin viewed these proposals with concern, advising Ulbricht to tone down the measures and slow down the intense pace of industrialisation that the East German leader insisted was necessary. For the workers of the German Democratic Republic, this was a lose-lose scenario.

East Germany’s economy was stagnating and Ulbricht (pictured), a Stalinist to the core, proposed a range of measures to pump up the economy – increase taxes, increase prices and increase production by 10% – but with no corresponding increase in wages. If the new quotas were not met, workers were told, wages would be cut by a third. The Kremlin viewed these proposals with concern, advising Ulbricht to tone down the measures and slow down the intense pace of industrialisation that the East German leader insisted was necessary. For the workers of the German Democratic Republic, this was a lose-lose scenario.

Citizens of post-war Eastern Europe did as their governments ordered, any protest was silent, whispered in dark corners. But these measures were too much; Ulbricht had gone too far.

Strike

On 16 June 1953, East Berlin construction workers downed tools. The following morning, 17 June, the strike had spread with over 40,000 demonstrators marching through the capital. Their demands at first focused on the economic – a return to the old work quotas. But then as the strike spread to other cities – Leipzig, Dresden, and some 400 cities and towns throughout East Germany, their voices gained strength and their hearts courage. They demanded increasingly more – free elections, a new government, democracy. Meetings were held; workers’ councils elected. In the East German town of Merseburg, workers stormed the police station and released prisoners from the jails.

Protestors tore down communist flags and carried banners proclaiming, ‘We want free elections; we are not slaves’, ‘Death to communism’, and ‘Long Live Eisenhower’. This was no longer a strike but an uprising.

Ulbricht turned to the Kremlin. Laventry Beria, Stalin’s former Chief of Secret Police and the man poised to take over now that Stalin was dead, sent in the tanks. The crews, 20,000 troops based in East Germany, were told by Beria not to “spare bullets”. This was a revolution and it needed crushing. (Six months later Beria was dead – executed by his Kremlin colleagues. One of the supposed reasons for his arrest was his heavy-handed dealing with the East German Uprising).

Ulbricht turned to the Kremlin. Laventry Beria, Stalin’s former Chief of Secret Police and the man poised to take over now that Stalin was dead, sent in the tanks. The crews, 20,000 troops based in East Germany, were told by Beria not to “spare bullets”. This was a revolution and it needed crushing. (Six months later Beria was dead – executed by his Kremlin colleagues. One of the supposed reasons for his arrest was his heavy-handed dealing with the East German Uprising).

Martial law was declared while, on the afternoon of the 17th, the tanks moved in and, alongside the East German police, opened fire. Down the Unter den Linden, people, demonstrators, civilians fell. How many were killed no one knows for sure. The figures vary considerably between sources based in the West and those of the East. But at least 40 were killed, possibly up to 260, and 400 wounded.

The West

If the East German protestors hoped for assistance from the West, they, like their counterparts during the Hungarian Revolution three years later, were to be disappointed. The US was not prepared to risk war over such an issue. But it did start a food aid programme, distributing over 5 million food parcels during July and August. Winston Churchill’s response, at the time prime minister, was also muted. According to the German historian, Hubertus Knabe, Churchill feared the resurgence of a united Germany so soon after the Second World War. While publicly supporting a united Germany, a divided one, he felt, was more secure. Churchill considered the regime’s response to the uprising as ‘restrained’.

Thus without the West’s intervention, pockets of resistance continued for a few weeks but the main thrust of the East German Uprising had been crushed within just 24 hours of starting.

And then started the reprisals – thousands arrested, perhaps up to 6,000, tortured and interned. Six ringleaders were executed. Walter Ulbricht took the opportunity of purging his party of seventy percent of its members.

During the Cold War, the human face of socialism only went so far and today, six decades on, Germany still remembers the uprising of 1953.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the Cold War in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Cold War (75 pages) available as paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

“Alone, deserted by his followers, broke and unpopular, Marcus Garvey, once leader of the greatest mass organization ever assembled by a member of the Race, died here during the last week in April.”

“Alone, deserted by his followers, broke and unpopular, Marcus Garvey, once leader of the greatest mass organization ever assembled by a member of the Race, died here during the last week in April.” Imre Nagy was born 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in southern Hungary. He worked as a locksmith before joining the Austrian-Hungary army during the First World War. In 1915, he was captured and spent much of the war as a prisoner of war in Russia. He escaped and having converted to communism, joined the Red Army and fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Imre Nagy was born 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in southern Hungary. He worked as a locksmith before joining the Austrian-Hungary army during the First World War. In 1915, he was captured and spent much of the war as a prisoner of war in Russia. He escaped and having converted to communism, joined the Red Army and fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Americans, it was decided, would land on the two western beaches in Normandy,

The Americans, it was decided, would land on the two western beaches in Normandy,  Born 24 June 1850 in County Kerry, Ireland, Horatio Kitchener first saw active service with the French army during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and, a decade later, with the British Army during the occupation of Egypt. He was part of the force that tried, unsuccessfully, to relieve General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum in 1885. The death of Gordon, at the hands of Mahdist forces, caused great anguish in Britain. Thirteen years later, as commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, Kitchener led the campaign of reprisal into Sudan, defeating the Mahdists at the Battle of Omdurman and reoccupying Khartoum in 1898. Kitchener had restored Britain’s pride.

Born 24 June 1850 in County Kerry, Ireland, Horatio Kitchener first saw active service with the French army during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and, a decade later, with the British Army during the occupation of Egypt. He was part of the force that tried, unsuccessfully, to relieve General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum in 1885. The death of Gordon, at the hands of Mahdist forces, caused great anguish in Britain. Thirteen years later, as commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, Kitchener led the campaign of reprisal into Sudan, defeating the Mahdists at the Battle of Omdurman and reoccupying Khartoum in 1898. Kitchener had restored Britain’s pride. In 1928, Hitler offered his sister the position of housekeeper in his Bavarian mountain retreat. Angela arrived with her two daughters, Elfriede and nineteen-year-old Angela, known as

In 1928, Hitler offered his sister the position of housekeeper in his Bavarian mountain retreat. Angela arrived with her two daughters, Elfriede and nineteen-year-old Angela, known as  On 24 May 1941, the Bismarck, on its first operation, had helped sink the

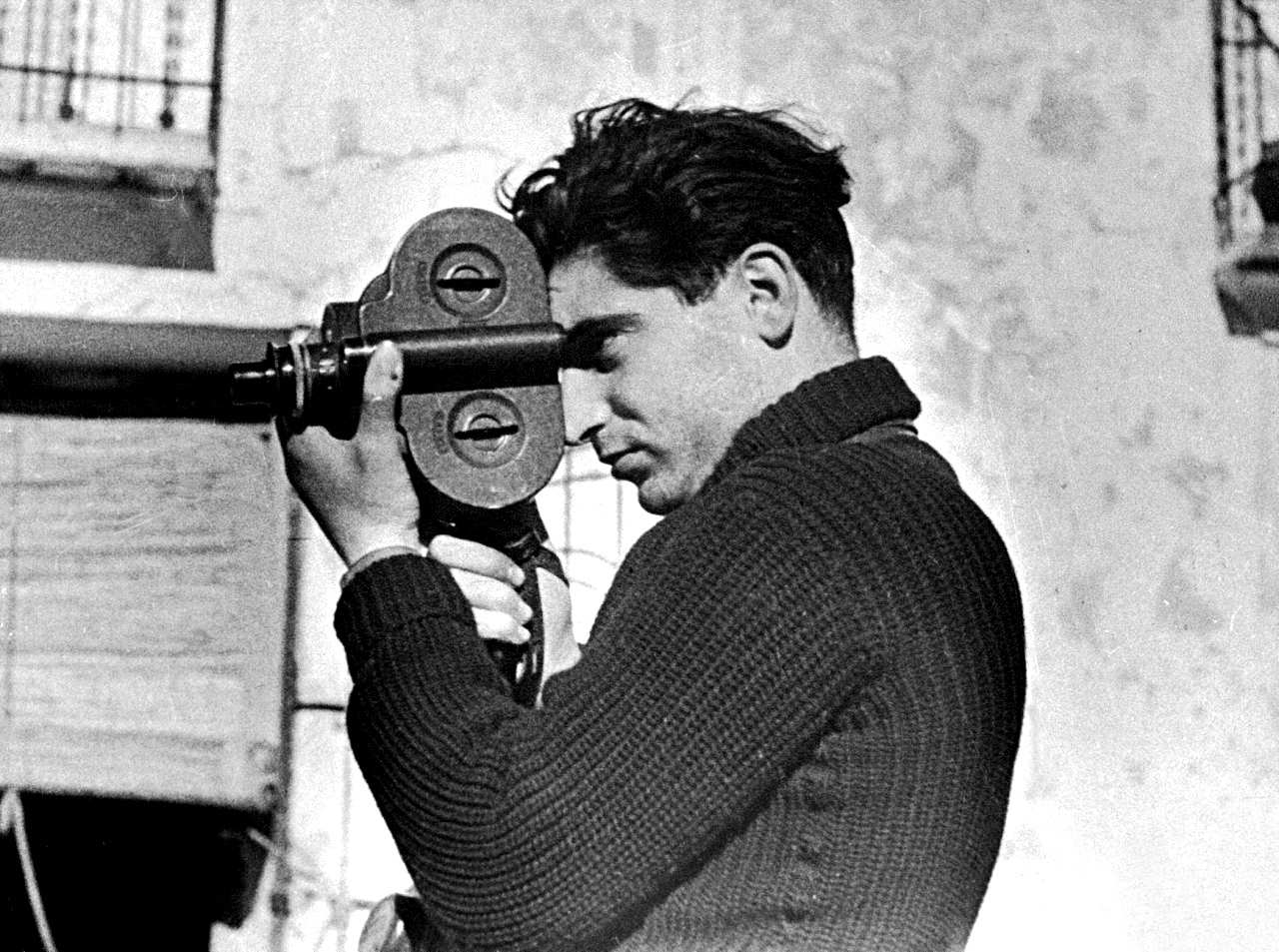

On 24 May 1941, the Bismarck, on its first operation, had helped sink the  Born Andre Friedmann in Budapest on 22 October 1913, Robert Capa had, by the age of eighteen, turned into a political radical, opposed to the authoritarian rule of Hungarian regent, Miklós Horthy. In 1931, Friedmann was arrested and imprisoned by Hungary’s secret police. On his release, after only a few months, he moved to

Born Andre Friedmann in Budapest on 22 October 1913, Robert Capa had, by the age of eighteen, turned into a political radical, opposed to the authoritarian rule of Hungarian regent, Miklós Horthy. In 1931, Friedmann was arrested and imprisoned by Hungary’s secret police. On his release, after only a few months, he moved to