With his rimless glasses and small physique, Heinrich Himmler’s appearance was at odds with his fearsome manner. Indeed, one English visitor observed, ‘nobody I met in Germany is more normal.’ A German officer described Himmler’s ‘slender, pale and almost girlishly soft hands … He looked to me like an intelligent elementary schoolteacher, certainly not a man of violence.’

Chicken farmer

Heinrich Himmler was born the son of a Catholic schoolteacher in Munich on 7 October 1900. After a stint in the army during the First World War, although he missed out on seeing active service, Himmler studied agriculture and held a number of jobs including that of a chicken farmer and a fertilizer salesman before joining the Nazi Party in 1921.

Heinrich Himmler was born the son of a Catholic schoolteacher in Munich on 7 October 1900. After a stint in the army during the First World War, although he missed out on seeing active service, Himmler studied agriculture and held a number of jobs including that of a chicken farmer and a fertilizer salesman before joining the Nazi Party in 1921.

Hardworking and meticulous, Himmler became devoted to Hitler and the Nazi cause. He took part in the failed putsch of 1923 in which Hitler tried to seize power in Bavaria. Between 1926 and 1930, Himmler acted as the Nazi party’s propaganda leader until, in 1929, Hitler appointed him head of the SS.

In 1934, Himmler became head of the Prussian division of the Gestapo and, two years later, head of all Nazi security organs. In 1933, soon after Hitler’s coming to power, Himmler established the first concentration camp at Dachau, near Munich, and in 1934, played a vital role in the elimination of Hitler’s opponents during the ‘Night of the Long Knives‘.

A page of glory

During the war, Himmler was responsible for co-ordinating the systematic murder of Jews and other victims of the Nazi regime, extending and expanding the network of concentration and death camps, and responsible for implementing the ‘Final Solution’.

Himmler suffered from various psychosomatic illnesses and intense headaches and was shocked and sickened by what he saw when visiting the camps he administered. Yet he remained determined that the work should continue, however distasteful.

Himmler suffered from various psychosomatic illnesses and intense headaches and was shocked and sickened by what he saw when visiting the camps he administered. Yet he remained determined that the work should continue, however distasteful.

On 4 October 1943, addressing an audience of SS officers in Posen, he said, ‘Whether or not 10,000 Russian women collapse from exhaustion while digging a tank ditch interests me only in so far as the tank ditch is completed for Germany … This is a page of glory in our history, which has never been written and is never to be written…. We had the moral right, we had the duty to our people, to destroy this people which wanted to destroy us.’

In India French first met his future rival,

In India French first met his future rival,  The Khodynka Tragedy

The Khodynka Tragedy Thomas Highgate was born in Shoreham in Kent on 13 May 1895. In February 1913, aged 17, he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. Within months, Highgate fell foul of the military authorities – in 1913, he

Thomas Highgate was born in Shoreham in Kent on 13 May 1895. In February 1913, aged 17, he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. Within months, Highgate fell foul of the military authorities – in 1913, he  Shoreham

Shoreham Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. “The seeds of totalitarian regimes,” said US president, Harry S. Truman, a year earlier in March 1947, “

“The seeds of totalitarian regimes,” said US president, Harry S. Truman, a year earlier in March 1947, “

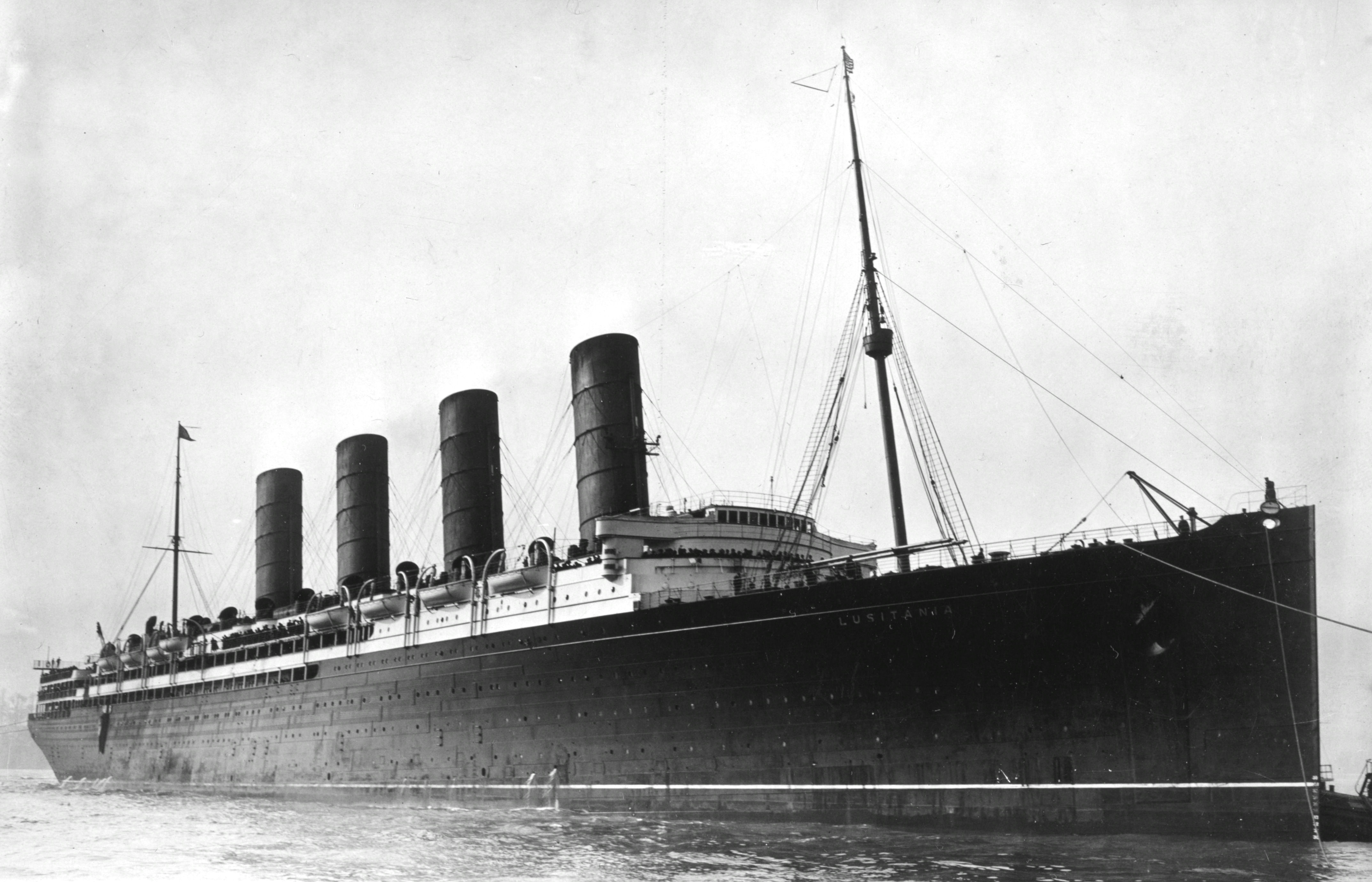

The ‘Great War’ was still less than a year old. On 18 February 1915, in response to Great Britain’s blockade of Germany, the Germans announced that it would, in future, be operating a policy of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. In other words, German U-boats would actively seek out and attack enemy shipping within the war zone of British waters. Even ships displaying a neutral flag, they announced, would be at risk – the Germans

The ‘Great War’ was still less than a year old. On 18 February 1915, in response to Great Britain’s blockade of Germany, the Germans announced that it would, in future, be operating a policy of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. In other words, German U-boats would actively seek out and attack enemy shipping within the war zone of British waters. Even ships displaying a neutral flag, they announced, would be at risk – the Germans  Wealthy passengers boarding the Lusitania, a 32,000-ton luxury Cunard liner, in New York saw an advertisement issued by the US German embassy warning them of the risk:

Wealthy passengers boarding the Lusitania, a 32,000-ton luxury Cunard liner, in New York saw an advertisement issued by the US German embassy warning them of the risk: Built in Germany in 1935 the 800-foot long Zeppelin airship, the Hindenburg, was considered the height of sophisticated travel. It may only have travelled at 80 mph yet it still provided the fastest means of crossing the Atlantic – twice as fast as the speediest ship. It was akin to being on a luxury liner and had already made dozens of journeys across the Atlantic from Germany to Brazil or America and back. Of course, it wasn’t cheap – a one-way ticket across the Atlantic cost about US$400 (about US$7,000 / £4,500 in 2016).

Built in Germany in 1935 the 800-foot long Zeppelin airship, the Hindenburg, was considered the height of sophisticated travel. It may only have travelled at 80 mph yet it still provided the fastest means of crossing the Atlantic – twice as fast as the speediest ship. It was akin to being on a luxury liner and had already made dozens of journeys across the Atlantic from Germany to Brazil or America and back. Of course, it wasn’t cheap – a one-way ticket across the Atlantic cost about US$400 (about US$7,000 / £4,500 in 2016).