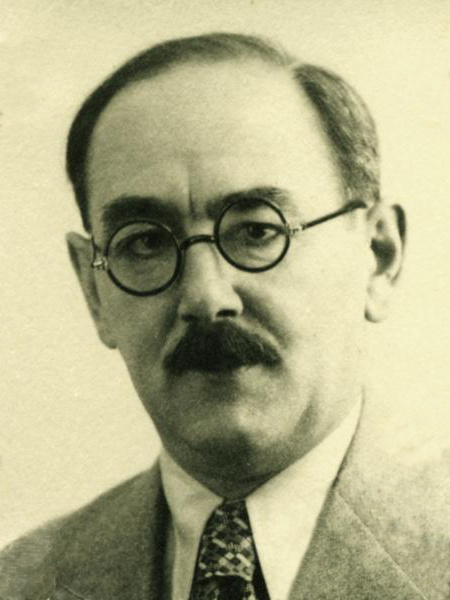

Hungarian cardinal, Joseph Mindszenty, came to symbolise the church’s opposition to tyranny and totalitarianism.

Born Joseph Pehm on 29 March 1892 in the Hungarian village of Csehi-Mindszent (the name which, in 1941, Pehm adopted), Mindszenty was ordained a priest in 1915 at the age of 23. He spoke out against Hungary’s short-lived Soviet Republic and was subsequently arrested and imprisoned until its collapse in August 1919.

Born Joseph Pehm on 29 March 1892 in the Hungarian village of Csehi-Mindszent (the name which, in 1941, Pehm adopted), Mindszenty was ordained a priest in 1915 at the age of 23. He spoke out against Hungary’s short-lived Soviet Republic and was subsequently arrested and imprisoned until its collapse in August 1919.

In March 1944, during the Second World War, he was consecrated as a bishop but later the same year was again imprisoned, this time by the Nazi-affiliated Arrow Cross government, for protesting against Hungary’s treatment and oppression of its Jewish population.

I stand for God

Following the war, he was appointed Primate of Hungary and Archbishop of Esztergom, and in 1946 was made a cardinal by Pope Pius XII. But by now, the Hungarian communist party was looking to take over power, intimidating and silencing all opposition.

Mindszenty opposed the Hungarian communist regime of Matyas Rakosi (pictured) and was known for his vocal criticism. The cardinal toured the country, urging people to resist the government’s plan to nationalize the church’s land and property and Hungary’s 4,813 Catholic schools. In a letter published written in November 1948 and broadcast on the Voice of America radio station, the cardinal said, ‘I stand for God, for the Church and for Hungary. . . . Compared with the sufferings of my people, my own fate is of no importance. I do not accuse my accusers. …I pray for those who, in the words of Our Lord, ‘know not what they do.’ I forgive them from the bottom of my heart.’

On 26 December 1948, Mindszenty was arrested. Stripped naked or dressed as a clown, Mindszenty was tortured, methods that included sleep deprivation, beatings, intense and incessant noise, and forced-fed mind-altering drugs. Finally, after over forty days and nights of continuous torture, the cardinal signed his confession.

On 26 December 1948, Mindszenty was arrested. Stripped naked or dressed as a clown, Mindszenty was tortured, methods that included sleep deprivation, beatings, intense and incessant noise, and forced-fed mind-altering drugs. Finally, after over forty days and nights of continuous torture, the cardinal signed his confession.

A blot upon the nation

Mindszenty appeared at his show trial washed, shaved, and dressed up in a new suit. He was accused of over forty farcical wrongdoings, such as planning to steal the Hungarian crown jewels and, according to the prosecution, of inciting the ‘American imperialists to declare war on our country’. ‘I am guilty on principle and in detail of most of the accusations made,’ he said, but denied that he was trying to topple the government. The verdict, of course, was a foregone conclusion, and after the six-day trial, on 8 February 1949, Cardinal Mindszenty was found guilty of treason. Escaping the death sentence (the communists wanted to avoid having a dead martyr on their hands), he was sentenced to life imprisonment. Four days later, the Pope excommunicated all those involved in the cardinal’s trial.

The verdict outraged the free world. Pius XII called the outcome a ‘serious outrage which inflicts a deep wound . . . on every upholder of the dignity and liberty of man.’ US president, Harry S Truman, said it was ‘one of the black spots on Hungary’s history and a blot upon the nation.’

The Cardinal is free

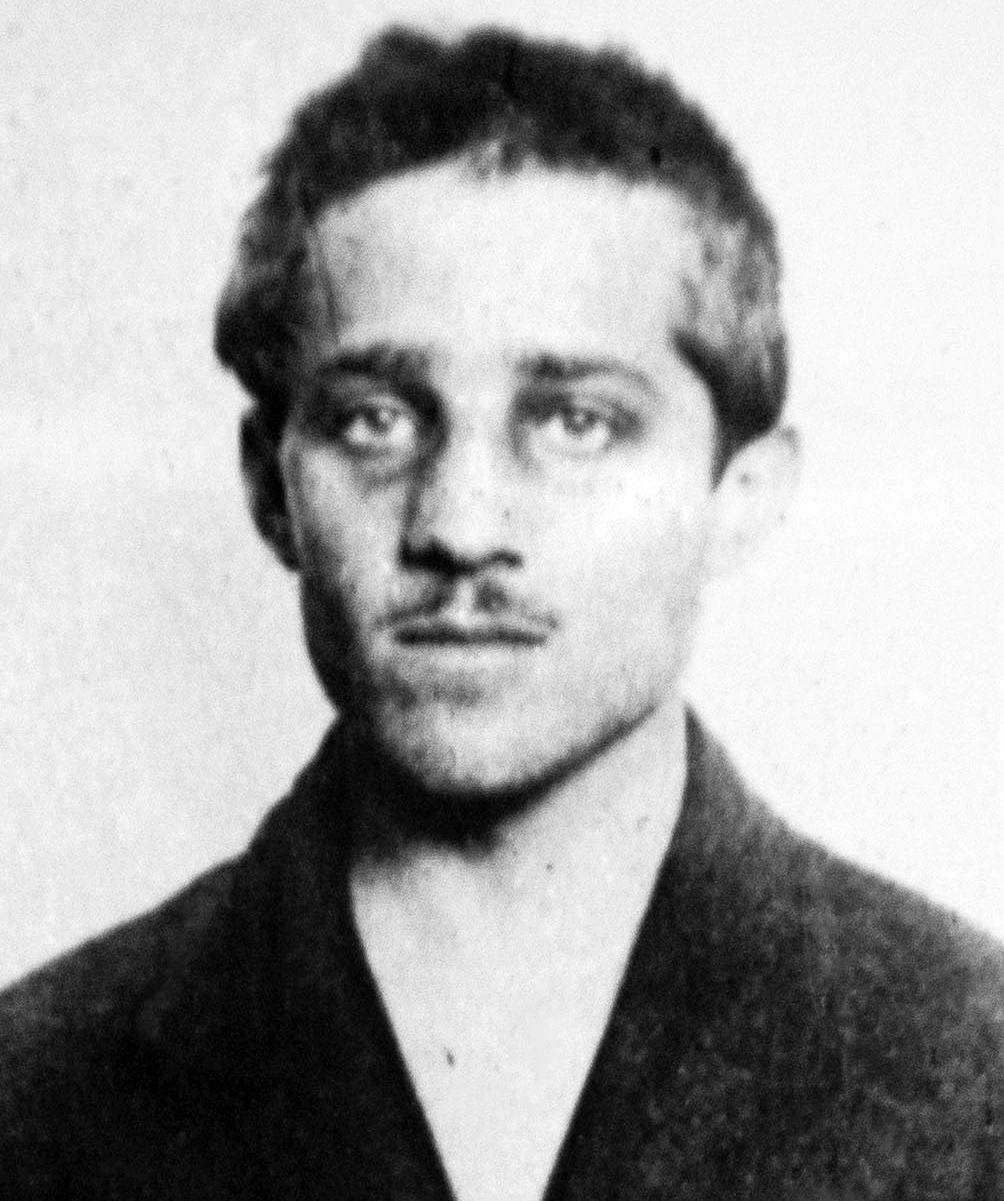

During the chaotic days of the Hungarian Revolution, 23 October to 4 November 1956, Hungary’s new leader, Imre Nagy (pictured), appointed by the Soviet politburo, sanctioned Mindszenty’s release, stating, ‘the measures depriving Cardinal Primate Joseph Mindszenty of his rights are invalid and that the Cardinal is free to exercise without restriction all his civil and ecclesiastical rights.’

During the chaotic days of the Hungarian Revolution, 23 October to 4 November 1956, Hungary’s new leader, Imre Nagy (pictured), appointed by the Soviet politburo, sanctioned Mindszenty’s release, stating, ‘the measures depriving Cardinal Primate Joseph Mindszenty of his rights are invalid and that the Cardinal is free to exercise without restriction all his civil and ecclesiastical rights.’

Mindszenty lived under voluntary house arrest within Budapest’s US embassy and stayed there for fifteen years. When the communists, again worried lest he should die and attain national martyrdom, offered him safe passage to Austria, he refused. Finally, in 1971, on the urging of both Pope Paul VI and US president, Richard Nixon, Mindszenty left Hungary and moved briefly into the Vatican before settling in Vienna.

Cardinal Mindszenty died in Vienna on 6 May 1975, aged 83. He was buried in the city but, following the fall of communism in Hungary, was reinterred in the Hungarian town of Esztergom.

Rupert Colley

Read more about the revolution in The Hungarian Revolution, 1956, available as ebook and paperback (124 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

It was near the beginning of the Cold War: the Soviet Union had surged ahead of America in the arms race, Chairman Mao had not long come to power in China, and Americans everywhere feared the presence of ‘Reds Under the Beds’ within their own communities. In stepped Joseph McCarthy to shock the nation with a sensational announcement that confirmed their worst fears.

It was near the beginning of the Cold War: the Soviet Union had surged ahead of America in the arms race, Chairman Mao had not long come to power in China, and Americans everywhere feared the presence of ‘Reds Under the Beds’ within their own communities. In stepped Joseph McCarthy to shock the nation with a sensational announcement that confirmed their worst fears. Born 10 March 1957, Osama bin Laden was one of 52 (or more) siblings born to his billionaire father, Mohammed, and his 22 wives. Osama’s mother, Alia, was 14 when she married Mohammed, his tenth wife, and 15 when she gave birth to Osama (‘young lion’ in Arabic). Osama was the only product of this union. His parents divorced soon after his birth.

Born 10 March 1957, Osama bin Laden was one of 52 (or more) siblings born to his billionaire father, Mohammed, and his 22 wives. Osama’s mother, Alia, was 14 when she married Mohammed, his tenth wife, and 15 when she gave birth to Osama (‘young lion’ in Arabic). Osama was the only product of this union. His parents divorced soon after his birth. One imagines there’s a degree of envy here – born on 29 October 1897, Joseph Goebbels was old enough to fight in the First World War but was rejected due to his clubfoot. (Throughout his life he had to wear a special shoe to compensate for his shorter leg.) After the war, he sometimes liked to pretend that his disability was in fact a war wound. In his novel, Michael, in common with Flisges, sees active service on the Eastern Front during the Great War; Michael’s war record a reflection of Goebbels’ wishful thinking.

One imagines there’s a degree of envy here – born on 29 October 1897, Joseph Goebbels was old enough to fight in the First World War but was rejected due to his clubfoot. (Throughout his life he had to wear a special shoe to compensate for his shorter leg.) After the war, he sometimes liked to pretend that his disability was in fact a war wound. In his novel, Michael, in common with Flisges, sees active service on the Eastern Front during the Great War; Michael’s war record a reflection of Goebbels’ wishful thinking. Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

A week later, just past midnight on 29 April, in a ten-minute ceremony, Hitler married his long-term partner,

A week later, just past midnight on 29 April, in a ten-minute ceremony, Hitler married his long-term partner,

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to Nazi Germany, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to Nazi Germany, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on  Alexander instigated a vast improvement in communication, namely expanding Russia’s rail network from just 660 miles of track (linking Moscow and St Petersburg) in the 1850s to over 14,000 miles within thirty years, which, in turn, aided Russia’s industrial and economic expansion.

Alexander instigated a vast improvement in communication, namely expanding Russia’s rail network from just 660 miles of track (linking Moscow and St Petersburg) in the 1850s to over 14,000 miles within thirty years, which, in turn, aided Russia’s industrial and economic expansion.

Exercise Tiger

Exercise Tiger Hess was one of the original members of the Nazi Party, joining in 1920. Three years later he was involved in the failed

Hess was one of the original members of the Nazi Party, joining in 1920. Three years later he was involved in the failed