In 1914, in Milan, the future fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, married Ida Dalser, a 34-year-old beautician who soon bore him a child, Benito Albino Mussolini. The marriage lasted just a few months and on 17 December 1915, before the birth of Benito Jr., Mussolini, at the time at home on army sick leave, married Rachele Guidi in a civil ceremony. Guidi had been his long-term mistress and mother to his first child, Edda, who had been born in 1910.

Mussolini and Rachele Guidi shared the same place of birth – the town of Predappio in the area of Forlì in northern Italy. Guidi had been born on 11 April 1890. She and Mussolini had first met when Mussolini appeared at her school as a stand-in teacher. Guidi’s father had warned her against marrying the penniless Mussolini: ‘That young man will starve you to death,’ he warned. After the death of her father, Guidi’s mother began a relationship with Mussolini’s widowed father.

Mussolini and Rachele Guidi shared the same place of birth – the town of Predappio in the area of Forlì in northern Italy. Guidi had been born on 11 April 1890. She and Mussolini had first met when Mussolini appeared at her school as a stand-in teacher. Guidi’s father had warned her against marrying the penniless Mussolini: ‘That young man will starve you to death,’ he warned. After the death of her father, Guidi’s mother began a relationship with Mussolini’s widowed father.

In December 1925, ten years after their civil marriage, Rachele and Mussolini were married in a Catholic church. It was less a romantic gesture than an attempt by Mussolini to ingratiate himself with the pope, Pius XI. The Mussolinis were to have five children.

As dictator, Mussolini preached about the importance of the family and liked to portray his own family as a model fascist household. But in truth, he had little time for his children and could number his lovers by the hundred. Rachele knew about her husband’s many indiscretions. In an interview with Life magazine in February 1966, Rachele said, ‘My husband had a fascination for women. They all wanted him. Sometimes he showed me their letters – from women who wanted to sleep with him or have a baby with him. It always made me laugh.’

A beautiful companion

In 1923, Rachele took on a lover of her own – according to Edda in an interview in 1995, shortly before her death and only broadcast in 2001. Rachele, according to Edda, told Mussolini, ‘You have many women. There is a person who loves me a lot, a beautiful companion.’ Mussolini may have been shocked but he did nothing to stop the affair, which, apparently, lasted several years.

In 1923, Rachele took on a lover of her own – according to Edda in an interview in 1995, shortly before her death and only broadcast in 2001. Rachele, according to Edda, told Mussolini, ‘You have many women. There is a person who loves me a lot, a beautiful companion.’ Mussolini may have been shocked but he did nothing to stop the affair, which, apparently, lasted several years.

(Pictured are Benito and Rachele Mussolini in 1923 with their first three children. Edda, their eldest, is on the right).

In fact, it was less Mussolini’s dalliances that worried Rachele, than his career in politics: ‘You can’t be happy in politics… one day things go well,’ she said, ‘another day things go badly.’ She admitted that she had been at her happiest when they were poor. ‘She never was,’ declared Life, ‘nor ever wanted to be, anything but a housewife’. She certainly disliked the trappings of being married to Italy’s most powerful man. She hated life in Rome and, refusing to live there, avoided the city at all costs. ‘If I lived in Rome,’ she told Life, ‘I’d be a communist.’

Mussolini was, by all accounts, fearful of his wife. Once, following an argument, she kicked him out of the house and made him have his dinner on the front steps. One friend remembered, ‘The Duce was more afraid of her than he was of the Germans.’

In 1930, Edda married Mussolini’s foreign secretary, Galeazzo Ciano. (During the Second World War, on 11 January 1944, Mussolini had his son-in-law executed, an act for which Edda never forgave her father: ‘The Italian people must avenge the death of my husband. If they do not, I’ll do it with my own hands.’) Another womanizer, Rachele disliked her daughter’s husband and made no attempt to disguise it.

The Mistress

In his latter years, while running the Salo Republic, Mussolini had his mistress, Clara Petacci (pictured), a woman two years younger than his eldest daughter, set up home nearby – much to Rachele Mussolini’s disgust. Wife and mistress frequently argued while Mussolini, the diminished dictator, cowered.

In his latter years, while running the Salo Republic, Mussolini had his mistress, Clara Petacci (pictured), a woman two years younger than his eldest daughter, set up home nearby – much to Rachele Mussolini’s disgust. Wife and mistress frequently argued while Mussolini, the diminished dictator, cowered.

Indeed, on one occasion, Rachele, accompanied by a minder, confronted Petacci. On arriving at the villa gates of her rival, Rachele kept her finger on the doorbell until Petacci’s own minder came out to tell her to go away. But Rachele forced her way in. On coming face to face with her husband’s mistress, she demanded that Petacci move out of the area. Petacci broke down in tears while Rachele called her names. Both minders waited anxiously in the wings. Petacci tried to read to Rachele letters sent to her by Mussolini. Unable to bear this, Rachele lunged at Petacci and had to be restrained by the minders.

Death at Lake Como

In April 1945, Mussolini, knowing the end was in sight, tried to flee to neutral Switzerland. His companion was not Rachele, his wife of thirty years, but Petacci. They were caught close to Lake Como very near to the Swiss border by Italian partisans and executed on 28 April.

Days after the end of the war, Rachele also tried to flee to Switzerland and was also apprehended at Como by partisans. Handed over to the Allies, she was interned by the Americans, where she volunteered to cook for her fellow inmates, before being released within a matter of months. Penniless, she and Edda lived in Rome, surviving on handouts before eventually returning to Predappio, her place of birth.

Rachele canvassed the Italian government to allow her to bury her husband’s body in Predappio. Finally, her wish was granted and in 1957, Mussolini was returned and buried within the family crypt. Immediately, Mussolini’s grave became a shrine for neo-fascists with frequent ‘pilgrimages’, especially on significant dates – his date of birth, 29 July, and death, 28 April.

Rachele canvassed the Italian government to allow her to bury her husband’s body in Predappio. Finally, her wish was granted and in 1957, Mussolini was returned and buried within the family crypt. Immediately, Mussolini’s grave became a shrine for neo-fascists with frequent ‘pilgrimages’, especially on significant dates – his date of birth, 29 July, and death, 28 April.

Meanwhile, dressed traditionally as a ‘black-cad mamma’, Rachele Mussolini kept chickens, tendered a garden, and opened a small restaurant within sight of a mock-medieval castle that Mussolini had built at the height of his power. The restaurant did well, as did a roaring side trade in selling postcards featuring her husband.

Mussolini’s brain

In March 1966, Rachele was handed an envelope by an American diplomat. Inside, bizarrely, was a piece of Mussolini’s brain which the Americans had removed from Mussolini’s corpse presumably, thought Rachele, because they ‘wanted to know what makes a dictator’. The Washington Post that year had reported that a ‘section’ of Mussolini’s brain had been ‘examined by pathologists who described it as average’. She placed the section of brain in a box above Mussolini’s grave.

Forty-three years later, in 2009, in another bizarre postscript, Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini (pictured), model turned politician, discovered that the Italian version of the online auction site, eBay, was listing three glass vials containing blood samples and more fragments of her grandfather’s brain with a starting price of 15,000 euros. On realising their mistake (eBay forbids the sale of body parts), the listing was immediately removed. Alessandra, niece to Sophia Loren, was, understandably, ‘outraged’.

Forty-three years later, in 2009, in another bizarre postscript, Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini (pictured), model turned politician, discovered that the Italian version of the online auction site, eBay, was listing three glass vials containing blood samples and more fragments of her grandfather’s brain with a starting price of 15,000 euros. On realising their mistake (eBay forbids the sale of body parts), the listing was immediately removed. Alessandra, niece to Sophia Loren, was, understandably, ‘outraged’.

In 1974, Rachele Mussolini published Mussolini: An Intimate Biography. She died, aged 89, on 30 October 1979.

What might have been

In 1910, while working as a journalist, the 27-year-old Mussolini was offered a job as a reporter in America. Rachele was pregnant with Edda at the time and therefore they decided against going. ‘I often wish we had,’ she said. ‘I think my husband might have been very successful in America.’

If only.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The war had been going badly for Mussolini’s Italy, so much so that a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 25 July 1943 voted to have Mussolini removed. One of those who voted against Mussolini was his son-in-law,

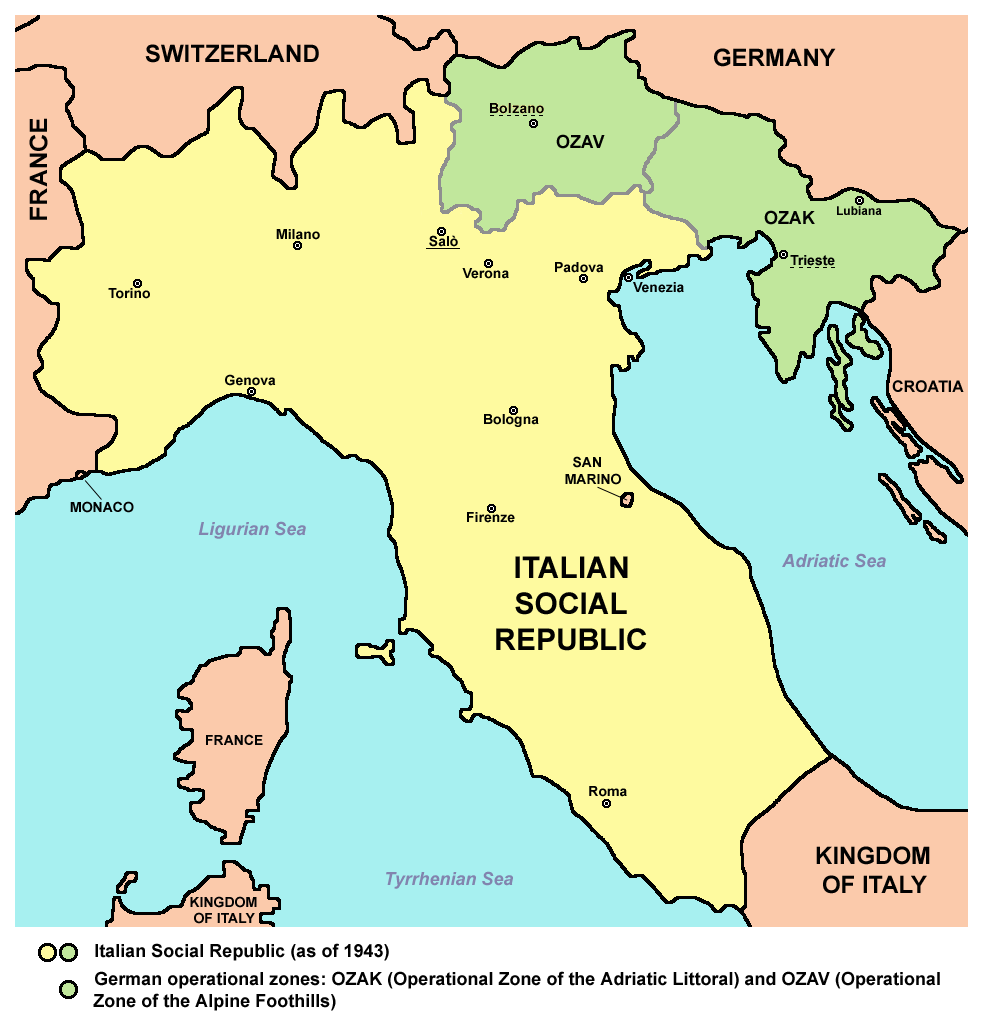

The war had been going badly for Mussolini’s Italy, so much so that a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 25 July 1943 voted to have Mussolini removed. One of those who voted against Mussolini was his son-in-law,  On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook.

On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook. While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife,

While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife,  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Joseph Stalin had died

Joseph Stalin had died On 15 April 1942, Malta received Britain’s highest civilian award for gallantry, the George Cross. But why would an island receive a medal?

On 15 April 1942, Malta received Britain’s highest civilian award for gallantry, the George Cross. But why would an island receive a medal? The Germans decided that Malta was causing too much damage and Albert Kesselring, Hitler’s Mediterranean commander, promised to “wipe Malta off the map.” Luftwaffe and U-boats stationed sixty miles north on the island of Sicily launched aerial attacks on Malta and the siege intensified. Supplies to the island virtually ceased and the inhabitants suffered eighteen months of hunger as well as continual bombardment. Civilians, starved and frightened, packed the caves beneath the capital Valletta.

The Germans decided that Malta was causing too much damage and Albert Kesselring, Hitler’s Mediterranean commander, promised to “wipe Malta off the map.” Luftwaffe and U-boats stationed sixty miles north on the island of Sicily launched aerial attacks on Malta and the siege intensified. Supplies to the island virtually ceased and the inhabitants suffered eighteen months of hunger as well as continual bombardment. Civilians, starved and frightened, packed the caves beneath the capital Valletta. Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. Mussolini and Rachele Guidi shared the same place of birth – the town of Predappio in the area of Forlì in northern Italy. Guidi had been born on 11 April 1890. She and Mussolini had first met when Mussolini appeared at her school as a stand-in teacher.

Mussolini and Rachele Guidi shared the same place of birth – the town of Predappio in the area of Forlì in northern Italy. Guidi had been born on 11 April 1890. She and Mussolini had first met when Mussolini appeared at her school as a stand-in teacher.  In 1923, Rachele took on a lover of her own – according to Edda in an interview in 1995, shortly before her death and only broadcast in 2001.

In 1923, Rachele took on a lover of her own – according to Edda in an interview in 1995, shortly before her death and only broadcast in 2001.  Forty-three years later, in 2009, in another bizarre postscript, Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini (pictured), model turned politician, discovered that the Italian version of the online auction site, eBay, was

Forty-three years later, in 2009, in another bizarre postscript, Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini (pictured), model turned politician, discovered that the Italian version of the online auction site, eBay, was

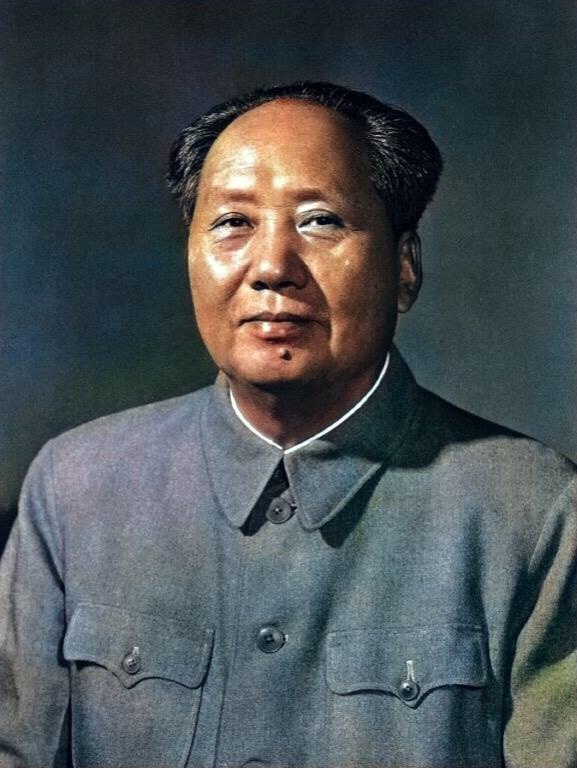

Although talking to a foreigner was deemed a crime in China, the two men, chatting through an interpreter, found a rapport. Zedong gave the American a silk gown by way of a present and invited the American team to play a friendly championship in China. This seemingly innocuous invitation has to be seen in the context of the time – no American had stepped on Chinese soil since Chairman Mao (pictured) had come to power 22 years earlier in 1949. Time magazine called it “The ping heard round the world.”

Although talking to a foreigner was deemed a crime in China, the two men, chatting through an interpreter, found a rapport. Zedong gave the American a silk gown by way of a present and invited the American team to play a friendly championship in China. This seemingly innocuous invitation has to be seen in the context of the time – no American had stepped on Chinese soil since Chairman Mao (pictured) had come to power 22 years earlier in 1949. Time magazine called it “The ping heard round the world.”