On 20 January 1942 took place one of the most notorious meetings in history. In a grand villa on the picturesque banks of Berlin’s Lake Wannsee, met fifteen high-ranking Nazis. Chaired by the chief of the security police, 37-year-old Reinhard Heydrich, the fifteen men represented various agencies of the Nazi apparatus.

‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’

Reinhard Heydrich‘s objective, as tasked by Hermann Göring (and therefore, presumably, Adolf Hitler), was to secure the support of these various agencies for the implementation of the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’, the systematic annihilation of the European Jew.

Reinhard Heydrich‘s objective, as tasked by Hermann Göring (and therefore, presumably, Adolf Hitler), was to secure the support of these various agencies for the implementation of the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’, the systematic annihilation of the European Jew.

Goring’s letter to Heydrich, dated July 1941, states, ‘I hereby command you to make all necessary organizational, functional, and material preparations for a complete solution of the Jewish Question in the German sphere of influence in Europe.’

The mass murder of Jews was already taking place. The initial method of shooting Jews on the edges of pits was considered too time-consuming and detrimental to the mental health of the murder squads. The squads, often recruited from the local populations in conquered areas, willingly collaborated in the killings but eventually found the task gruelling. Seeking alternative methods, the Germans began experimenting with gas, using carbon monoxide in mobile units, but although better this was still considered too slow and inefficient. Eventually, after experiments on Soviet prisoners of war in Auschwitz during September 1941, Zyklon B gas was discovered as a rapid and efficient means of murder.

The Wannsee Conference, as it became known, discussed escalating the killing to a new, industrial level. Heydrich estimated that 11 million Jews still resided in Europe and needed to be “combed from West to East.” He produced a list of nations and their respective number of Jews, not only in countries already under Nazi occupation but also neutral nations and those not yet occupied. For example, Britain, according to Heydrich’s figures, contained 330,000 Jews; Sweden 8,000; Spain 6,000; Switzerland 18,000; and Ireland 4,000, plus 200 Jews in Albania.

“Eliminated through natural reduction” Continue reading

At the time of his birth, Goring’s parents were stationed in Haiti, his father working for the German consul there. His mother returned to Germany to give birth, then promptly returned to Haiti, leaving baby Hermann with a friend, not to see her child again for three years.

At the time of his birth, Goring’s parents were stationed in Haiti, his father working for the German consul there. His mother returned to Germany to give birth, then promptly returned to Haiti, leaving baby Hermann with a friend, not to see her child again for three years. The ‘Communist culprit’ was

The ‘Communist culprit’ was

Born 7 June 1837, Alois Schicklgruber was the son of a 42-year-old unmarried

Born 7 June 1837, Alois Schicklgruber was the son of a 42-year-old unmarried  The object of the Jews

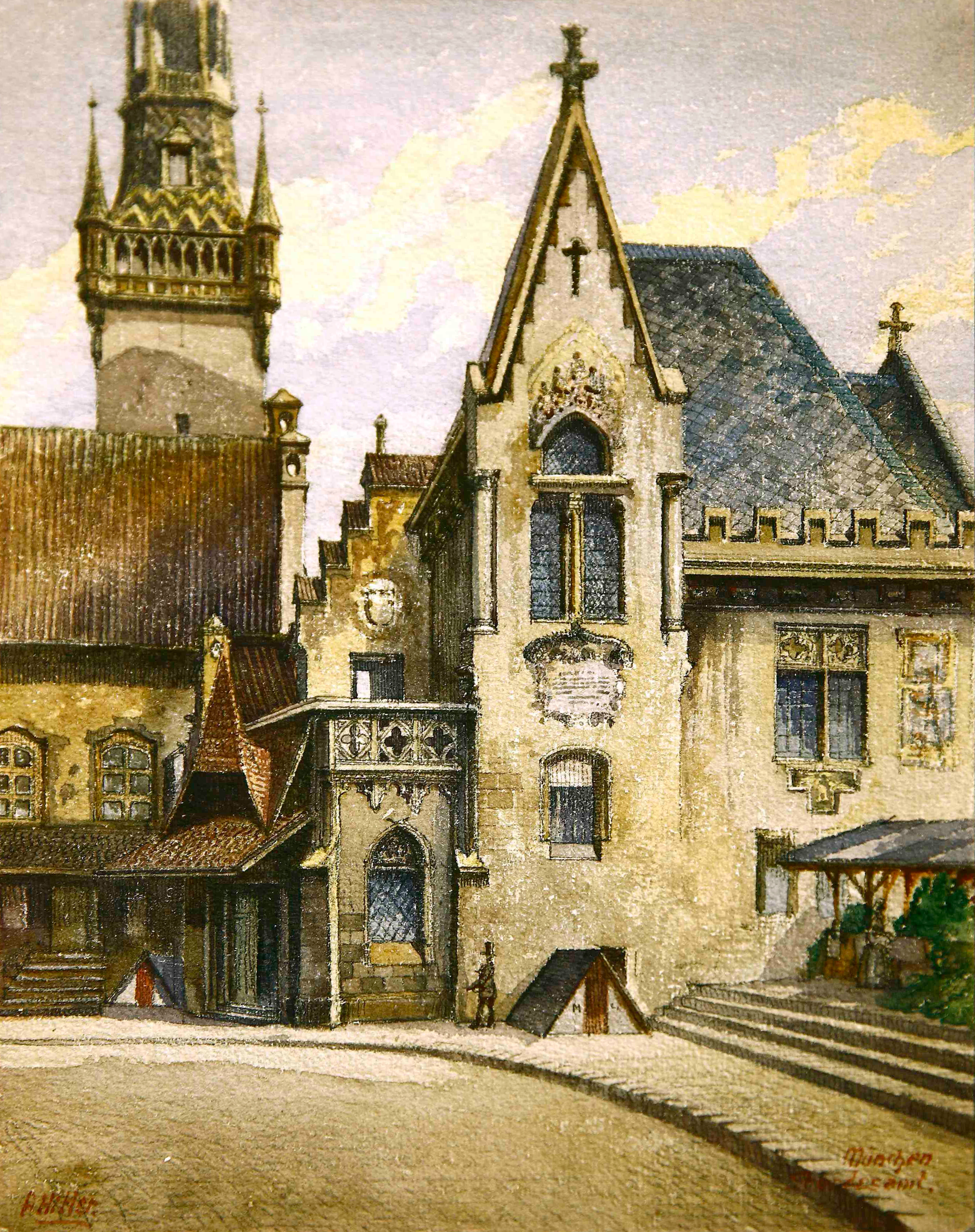

The object of the Jews  So how did the future dictator start off as an artist?

So how did the future dictator start off as an artist? Born 28 November 1887, Ernst Rohm fought with distinction throughout the First World War, winning an Iron Cross, First Class, and attaining the rank of captain. Twice he was wounded, on one occasion shot in the face, and he carried the scars for the rest of his life. In 1918, as the war drew to its close, Rohm contracted the

Born 28 November 1887, Ernst Rohm fought with distinction throughout the First World War, winning an Iron Cross, First Class, and attaining the rank of captain. Twice he was wounded, on one occasion shot in the face, and he carried the scars for the rest of his life. In 1918, as the war drew to its close, Rohm contracted the