Tanya Savicheva died near her hometown of Leningrad on 1 July 1944, aged only 14. Who was Tanya Savicheva? The name in Russia is what Anne Frank is to the West – a young innocent victim of World War Two, who left behind a small but lasting legacy.

But whereas Anne’s diary is a carefully kept journal over a period of two years, Tanya’s was little more than a few scribbled lines over six sheets of notepaper.

But whereas Anne’s diary is a carefully kept journal over a period of two years, Tanya’s was little more than a few scribbled lines over six sheets of notepaper.

Leningrad Siege

Leningrad (modern-day St Petersburg) was in the midst of a devastating 900-day blockade that lasted from September 1941 until January 1944. The German army had laid siege to the city, bombarded it, and cut off all supplies in its attempt to ‘wipe it off the map’, as Hitler had ordered.

The Savicheva family had all answered the call to help bolster the city’s defences. Tanya, only 11 years old, helped dig anti-tank trenches. On 12 September 1941, the largest food warehouse, the Badayev, was destroyed, having been bombed with German incendiaries. Three thousand tonnes of flour burned, thousands of tons of grain went up in smoke, meat frazzled, butter melted, and sugar turned molten and seeped into the cellars. ‘The streets that night ran with melted chocolate,’ said one witness, ‘and the air was rich and sticky with the smell of burning sugar.’ The situation, already severe, became critical.

Road of Life

Although trade unions were banned, Father

Although trade unions were banned, Father  then, in 1938, at the height of Stalin’s purges, Bystrolyotov was arrested by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. Tortured and crippled, and made to ‘confess’ to fantastical charges, he was sentenced to 20 years of hard

then, in 1938, at the height of Stalin’s purges, Bystrolyotov was arrested by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. Tortured and crippled, and made to ‘confess’ to fantastical charges, he was sentenced to 20 years of hard  Despairing, Yusupov shot Rasputin in the back and then, satisfied, left to join his fellow conspirators. Returning a little later to check on the body, Rasputin sat up and lunged at the prince. The prince’s friends came to his rescue, shooting the ‘mad monk’ a further three times, once in the forehead. But still refusing to die, Rasputin’s attackers resorted to clubbing him senseless then wrapping his body in a blue rug and throwing him in the icy waters of the River Neva.

Despairing, Yusupov shot Rasputin in the back and then, satisfied, left to join his fellow conspirators. Returning a little later to check on the body, Rasputin sat up and lunged at the prince. The prince’s friends came to his rescue, shooting the ‘mad monk’ a further three times, once in the forehead. But still refusing to die, Rasputin’s attackers resorted to clubbing him senseless then wrapping his body in a blue rug and throwing him in the icy waters of the River Neva.

A lover of Rachmaninov’s music and a cuddly uncle-figure to Svetlana Alliluyeva, pictured, Beria had his bodyguards abduct young girls off the streets for his devious sexual pleasure. Those that refused his predatory advances risked being packed off to a gulag.

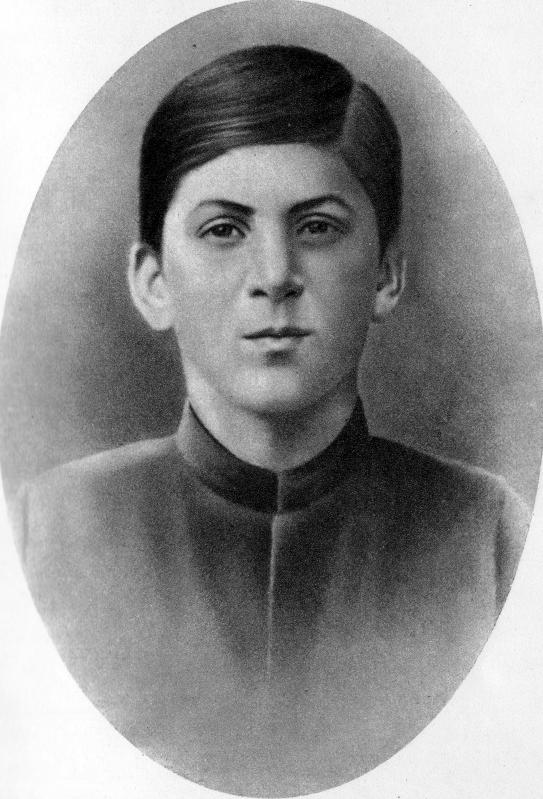

A lover of Rachmaninov’s music and a cuddly uncle-figure to Svetlana Alliluyeva, pictured, Beria had his bodyguards abduct young girls off the streets for his devious sexual pleasure. Those that refused his predatory advances risked being packed off to a gulag. Joseph Stalin’s father, Vissarion Dzhugashvili, known as Basu, was a shoemaker. An alcoholic, he spent much of his time in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, 50 miles east of Gori) producing shoes for the Russian army. On his drunken and increasingly rare appearances at home, he would beat his wife and son. (Pictured is Stalin, aged 15, in 1894).

Joseph Stalin’s father, Vissarion Dzhugashvili, known as Basu, was a shoemaker. An alcoholic, he spent much of his time in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, 50 miles east of Gori) producing shoes for the Russian army. On his drunken and increasingly rare appearances at home, he would beat his wife and son. (Pictured is Stalin, aged 15, in 1894). Together they had a son,

Together they had a son,  During the Second World War, the city of Leningrad (modern-day St Petersburg) was in the midst of a devastating 900-day blockade that lasted from September 1941 until January 1944. The German army had laid siege to the city, bombarded it and cut off all supplies in its attempt to ‘wipe it off the map’, as Hitler had ordered.

During the Second World War, the city of Leningrad (modern-day St Petersburg) was in the midst of a devastating 900-day blockade that lasted from September 1941 until January 1944. The German army had laid siege to the city, bombarded it and cut off all supplies in its attempt to ‘wipe it off the map’, as Hitler had ordered. Sergei Kirov, a dashing forty-seven-year-old and the rising star of the Bolshevik party, was killed on 1 December 1934 in a corridor outside his offices of the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. His assassin, 30-year-old Leonid Nikolaev, had acted alone. Kirov’s death threw the nation into a state of shock. Joseph Stalin, who rarely left the Kremlin, made an exception and caught the overnight train to Leningrad specifically to interview Nikolaev. Upon arriving in the city, Stalin was greeted by the

Sergei Kirov, a dashing forty-seven-year-old and the rising star of the Bolshevik party, was killed on 1 December 1934 in a corridor outside his offices of the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. His assassin, 30-year-old Leonid Nikolaev, had acted alone. Kirov’s death threw the nation into a state of shock. Joseph Stalin, who rarely left the Kremlin, made an exception and caught the overnight train to Leningrad specifically to interview Nikolaev. Upon arriving in the city, Stalin was greeted by the