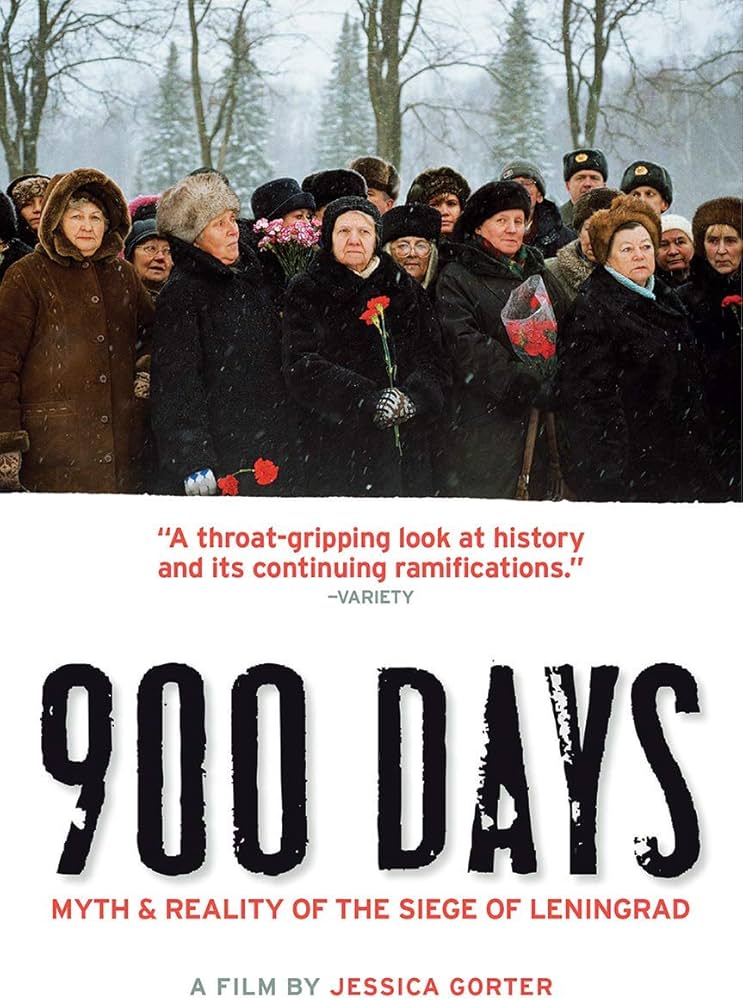

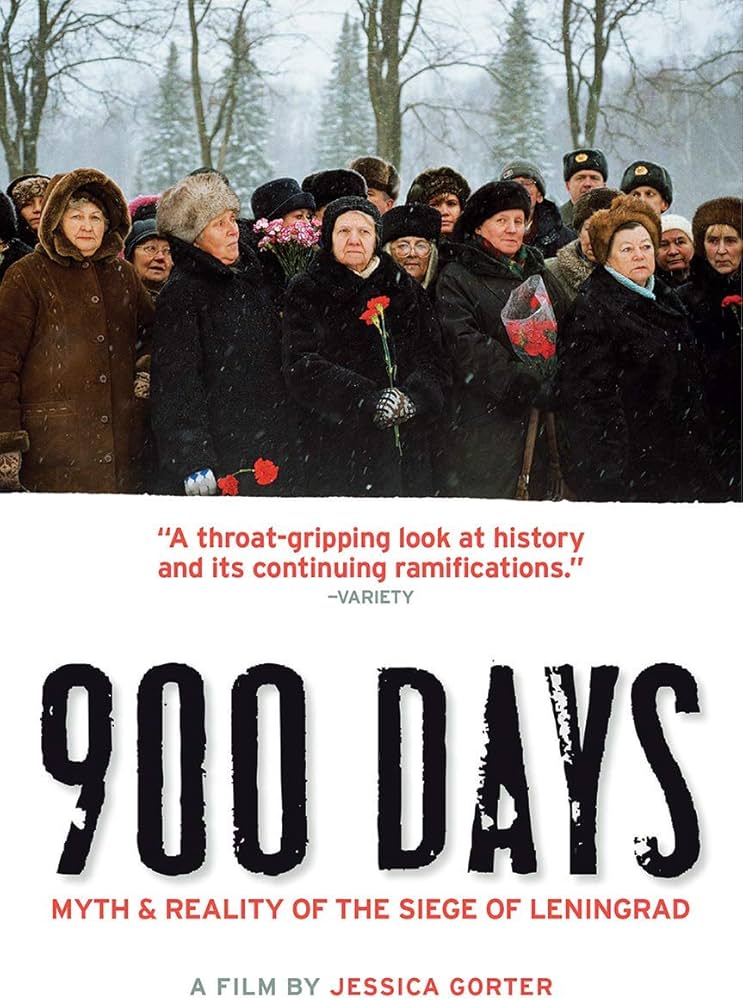

Four years in the making, Jessica Gorter’s film, 900 Days: the Myth and Reality of the Leningrad Blockade, considers how the Siege of Leningrad was acknowledged in the Soviet Union during the post-war years and how, seventy years on, it’s remembered by those who lived through it.

Over twenty-nine months, between 1941 and 1944, German forces encircled the city of Leningrad (now St Petersburg) and subjected it to a devastating siege. The number of deaths in Leningrad during the war exceeds those who died from the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and constitutes the largest death toll ever recorded in a single city.

Over twenty-nine months, between 1941 and 1944, German forces encircled the city of Leningrad (now St Petersburg) and subjected it to a devastating siege. The number of deaths in Leningrad during the war exceeds those who died from the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and constitutes the largest death toll ever recorded in a single city.

Hero City

For almost nine hundred days, the city resisted the Germans pounding at its gates. Its survival contributed to the defeat of Nazism. But the price was heavy – over one million died in Leningrad from German bombs and artillery, or from disease, the cold or starvation.

In its suffering, Leningrad became a source of symbolic national pride, of good conquering evil. The story of the siege is one of heroic resistance and stoical survival but it is also one of unimaginable suffering and extreme deprivation.

In the immediate aftermath of the siege, Leningrad, awarded the Order of Lenin, was held up as the pinnacle of Soviet endurance, spirit and heroic suffering. It was given the accolade, ‘Hero City’, which not even Moscow had achieved. The one million that died, did so nobly – ‘on the altar of the Motherland’. Those who had survived were awarded the Defence of Leningrad Medal.

Yes, the city had suffered but that it survived was a testament to the political strength of its people and their belief in Communism which had triumphed over Hitler’s fascist hoards. At least that’s the version perpetuated by Joseph Stalin. Leningrad’s torment became a banner for propaganda.

But there is nothing noble about death in such circumstances, nothing ideological about the city’s survival. The real stories that emerged from the siege had to be repressed. No one dared write or mention aloud the darkest aspects of the siege. Any mention of cannibalism was taboo. Diaries too explicit in the truth were confiscated, their authors labelled enemies of the people. A museum dedicated to the siege, opened in 1946, was deemed too bleak in its honest portrayal of what happened and was closed within three years, its director arrested. Stalin required suffering on a heroic scale, not the sordid, pitying suffering endured by so many for so long.

‘We bow deeply’

Almost seven decades after the event, Dutch filmmaker, Jessica Gorter, interviewed several survivors of the siege. The result, 900 Days, is a stunning testament to how these ordinary and now frail citizens, who, as children, suffered such hardship and hopelessness, survived both the siege itself and the years of myth and lies after.

Almost seven decades after the event, Dutch filmmaker, Jessica Gorter, interviewed several survivors of the siege. The result, 900 Days, is a stunning testament to how these ordinary and now frail citizens, who, as children, suffered such hardship and hopelessness, survived both the siege itself and the years of myth and lies after.

The film opens and closes with the annual celebration in Russia marking the Soviet Union’s triumph over the fascists. We see huge parades of soldiers and tanks parading across Moscow’s Red Square, bombastic and militaristic, reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s glory days. Prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev, says that today’s younger generations ‘bow deeply’ before yesterday’s heroes. We see veterans weighed down with medals lapping up the praise and gratitude. For them, having been forbidden to talk about their experiences for many decades, it is a cathartic process.

But for many, the medals are mere bits of tin and the speeches and parades are little more than empty gestures. One elderly couple, watching on TV, decide to turn off such ‘nonsense and lies’. So is it, asks Gorter in her film, better to acknowledge the almost unpalatable truth of what really happened during the siege, or to embrace the comfort of a myth?

Victims

‘Our generation,’ says one interviewee, ‘were not heroes but victims. We were children.’ This is from Lenina, 79 at the time of the interview but who passed away last year. She described how her sister, four years older, died from starvation during the siege. Her mother openly declared she’d lost the will to live. ‘What about me?’ asked Lenina pathetically, ‘You can go live with the neighbours or an orphanage,’ came the devastating reply. Sure enough, her mother died soon afterwards. Lenina owned a cat, Stripey. As hunger took hold and temperatures plummeted to minus 30 degrees and with no wood left for heating, she, along with a neighbour, held Stripey down, and chopped off its head, and then cooked and ate the former pet. Well, it was her birthday, Lenina tells us with a mischievous grin, sitting at her table in her dark and dank apartment surrounded by cats, her eleventh birthday.

‘Our generation,’ says one interviewee, ‘were not heroes but victims. We were children.’ This is from Lenina, 79 at the time of the interview but who passed away last year. She described how her sister, four years older, died from starvation during the siege. Her mother openly declared she’d lost the will to live. ‘What about me?’ asked Lenina pathetically, ‘You can go live with the neighbours or an orphanage,’ came the devastating reply. Sure enough, her mother died soon afterwards. Lenina owned a cat, Stripey. As hunger took hold and temperatures plummeted to minus 30 degrees and with no wood left for heating, she, along with a neighbour, held Stripey down, and chopped off its head, and then cooked and ate the former pet. Well, it was her birthday, Lenina tells us with a mischievous grin, sitting at her table in her dark and dank apartment surrounded by cats, her eleventh birthday.

We have a couple where the wife shows Gorter her Defence of Leningrad medal, awarded to survivors of the siege. Had she ever worn it, asks Gorter. No, not ever, came the emphatic reply. The medal meant nothing to her. She pushes it across the table, ‘It’s for you,’ says the husband. Gorter tries to push it back.

The film quotes an NKVD (Secret Police) report addressed to its boss in Moscow, Laventry Beria. Leningrad NKVD officers had apprehended a man carrying a suitcase, inside of which were two human legs. The man confessed to having sawn them off a corpse left lying, among the hundreds, unattended in the cemeteries. Without food, no one had the strength to dig through the frozen soil to bury the dead. Such was the extent of this man’s hunger, he took the risk. We can only guess his fate but it’s highly probable that he would have been executed, NVKD-style, with a bullet in the back of the neck.

The wife of one of the couples interviewed by Gorter remembers seeing corpses stripped of flesh – buttocks, thighs, breasts. Her husband disagrees that they had been the victims of cannibalism and argues they were probably patients operated on in hospital that died. His wife looks at him disdainfully. She knows the truth and if only he admitted it, so does he.

For Stalin

But for every interviewee prepared to talk, there are many who still, after all these years, cannot. One such person, the chair of a siege association, a well-dressed woman, can only talk in terms of defending the Motherland and how inspired she was by Stalin. Only Stalin could have won the war for the Soviet Union. Her view is a common one in Russia today, including Vladimir Putin who recently said, ‘Whatever anyone may say, victory [in World War Two] was achieved. Even when we consider the losses, nobody can now throw stones at those who planned and led this victory.’ The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 is, for our chairwoman, still a cause for profound regret.

But for every interviewee prepared to talk, there are many who still, after all these years, cannot. One such person, the chair of a siege association, a well-dressed woman, can only talk in terms of defending the Motherland and how inspired she was by Stalin. Only Stalin could have won the war for the Soviet Union. Her view is a common one in Russia today, including Vladimir Putin who recently said, ‘Whatever anyone may say, victory [in World War Two] was achieved. Even when we consider the losses, nobody can now throw stones at those who planned and led this victory.’ The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 is, for our chairwoman, still a cause for profound regret.

In one of the most poignant moments in the film, of which there are many, a woman recalls her father, arrested in the post-war years as an enemy of the people. Sentenced to work hard labour in uranium mines, he contracted cancer. Sent home in 1967 to die and no longer afraid of the authorities, he told his daughter what life was like during and after the siege as Stalin clamped down on the city. The things he said haunt her still. When Gorter gently pushes her to reveal, she clams up, unable to talk further, and we see her eyes drift away to those dark, frightening times.

Having been denied the chance to tell the truth for so long, when the time finally came, after the fall of the Soviet Union, the survivors found that no one was listening. People had moved on from the war. We see one of our couples being visited by their middle-aged son and daughter-in-law and grandchild. The son, sporting a ponytail, confesses his lack of interest in the war and looks positively bored as his mother talks of the siege to Gorter. Skip a generation and we see a group of young uniformed cadets being shown around the St Petersburg Museum devoted to the blockade. On seeing the stark images, one poor boy faints. The interest is returning. Today’s children want to know what happened to their grandparents during the war, and are being taught in schools. Even Prime Minister Medvedev, with his military parades and hamfisted jingoism, is playing his part. And also, on a lesser scale, but far more honestly, is Jessica Gorter and her film, 900 Days.

Rupert Colley.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Known for his uncompromising discipline, Georgy Zhukov placed strategic objectives far above the safety of the men he put into battle. Yet, despite his toughness, he could be rendered a wreck by a single harsh word from Soviet dictator, Joseph Stalin. During the early days of the war, he was once reduced to tears by an angry Stalin and had to take the handkerchief offered by Vyacheslav Molotov.

Known for his uncompromising discipline, Georgy Zhukov placed strategic objectives far above the safety of the men he put into battle. Yet, despite his toughness, he could be rendered a wreck by a single harsh word from Soviet dictator, Joseph Stalin. During the early days of the war, he was once reduced to tears by an angry Stalin and had to take the handkerchief offered by Vyacheslav Molotov. The Germans had

The Germans had  Having been accepted as a partisan, despite her tender age, Zoya was given the name ‘Tanya’. Handed a revolver and trained how to use it, she was assigned to a small group of partisans and given instructions. Their first task was to lay mines on the Volokolamsk highway, just behind

Having been accepted as a partisan, despite her tender age, Zoya was given the name ‘Tanya’. Handed a revolver and trained how to use it, she was assigned to a small group of partisans and given instructions. Their first task was to lay mines on the Volokolamsk highway, just behind  Over twenty-nine months, between 1941 and 1944, German forces encircled the city of Leningrad (now St Petersburg) and subjected it to a devastating siege. The number of deaths in Leningrad during the war exceeds those who died from the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and constitutes the largest death toll ever recorded in a single city.

Over twenty-nine months, between 1941 and 1944, German forces encircled the city of Leningrad (now St Petersburg) and subjected it to a devastating siege. The number of deaths in Leningrad during the war exceeds those who died from the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and constitutes the largest death toll ever recorded in a single city. Almost seven decades after the event, Dutch filmmaker, Jessica Gorter, interviewed several survivors of the siege. The result,

Almost seven decades after the event, Dutch filmmaker, Jessica Gorter, interviewed several survivors of the siege. The result,  ‘Our generation,’ says one interviewee, ‘were not heroes but victims. We were children.’ This is from Lenina, 79 at the time of the interview but who passed away last year. She described how her sister, four years older, died from starvation during the siege. Her mother openly declared she’d lost the will to live. ‘What about me?’ asked Lenina pathetically, ‘You can go live with the neighbours or an orphanage,’ came the devastating reply. Sure enough, her mother died soon afterwards. Lenina owned a cat, Stripey. As hunger took hold and temperatures plummeted to minus 30 degrees and with no wood left for heating, she, along with a neighbour, held Stripey down, and chopped off its head, and then cooked and ate the former pet. Well, it was her birthday, Lenina tells us with a mischievous grin, sitting at her table in her dark and dank apartment surrounded by cats, her eleventh birthday.

‘Our generation,’ says one interviewee, ‘were not heroes but victims. We were children.’ This is from Lenina, 79 at the time of the interview but who passed away last year. She described how her sister, four years older, died from starvation during the siege. Her mother openly declared she’d lost the will to live. ‘What about me?’ asked Lenina pathetically, ‘You can go live with the neighbours or an orphanage,’ came the devastating reply. Sure enough, her mother died soon afterwards. Lenina owned a cat, Stripey. As hunger took hold and temperatures plummeted to minus 30 degrees and with no wood left for heating, she, along with a neighbour, held Stripey down, and chopped off its head, and then cooked and ate the former pet. Well, it was her birthday, Lenina tells us with a mischievous grin, sitting at her table in her dark and dank apartment surrounded by cats, her eleventh birthday. But for every interviewee prepared to talk, there are many who still, after all these years, cannot. One such person, the chair of a siege association, a well-dressed woman, can only talk in terms of defending the Motherland and how inspired she was by Stalin. Only Stalin could have won the war for the Soviet Union. Her view is a common one in Russia today, including Vladimir Putin who recently said, ‘Whatever anyone may say, victory [in World War Two] was achieved. Even when we consider the losses, nobody can now throw stones at those who planned and led this victory.’ The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 is, for our chairwoman, still a cause for profound regret.

But for every interviewee prepared to talk, there are many who still, after all these years, cannot. One such person, the chair of a siege association, a well-dressed woman, can only talk in terms of defending the Motherland and how inspired she was by Stalin. Only Stalin could have won the war for the Soviet Union. Her view is a common one in Russia today, including Vladimir Putin who recently said, ‘Whatever anyone may say, victory [in World War Two] was achieved. Even when we consider the losses, nobody can now throw stones at those who planned and led this victory.’ The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 is, for our chairwoman, still a cause for profound regret.