On 29 July 1900, the king of Italy, Umberto I, was assassinated. The throne passed to his 30-year-old son, who, as Victor Emmanuel III, would reign until 1946, a period which saw both world wars and the rise and fall of Benito Mussolini’s fascists.

Born in Naples on 11 November 1869, the future king was so short, the German kaiser, Wilhelm II, nicknamed him the dwarf, and, in private, Mussolini called him the ‘little sardine’. He ruled over an Italy that had been in existence as a unified nation only since 1871. Despite unification, Italy was a deeply-fragmented society, steeped in poverty and corruption, and ruled over by a succession of weak coalition governments. But, as a figurehead king, Victor Emmanuel III chose to ignore the affairs of state, preferring instead to focus on his vast collection of coins.

Born in Naples on 11 November 1869, the future king was so short, the German kaiser, Wilhelm II, nicknamed him the dwarf, and, in private, Mussolini called him the ‘little sardine’. He ruled over an Italy that had been in existence as a unified nation only since 1871. Despite unification, Italy was a deeply-fragmented society, steeped in poverty and corruption, and ruled over by a succession of weak coalition governments. But, as a figurehead king, Victor Emmanuel III chose to ignore the affairs of state, preferring instead to focus on his vast collection of coins.

World War One

With the outbreak of war in July 1914, Italy initially adopted a position of neutrality despite having been in alliance, the Triple Alliance, with Germany and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire since 1882. Victor Emmanuel favoured participation in the war, partly as a means of enhancing Italy’s reputation on the international stage. Italy duly entered the war in May 1915, not as allies of Germany and Austria-Hungary, but on the side of the Triple Entente allies – France, Russia and Great Britain.

Mussolini

After 1918, Victor Emmanuel again retired to the sidelines as Italy struggled to cope with the post-war instabilities of demobilization, unemployment and inflation. Socialists, communists, anarchists and the newly-formed fascists fought on the streets and on the farms in a vicious cycle of ever-increasing violence.

In October 1922, with the country on the verge of civil war, the rising star of Italy’s right, Benito Mussolini, led the fascist March on Rome, demanding to form a new government. At first, Victor Emmanuel resisted but then, fearing outright anarchy, bowed to Mussolini’s persistence.

The murder of a leading socialist politician and outspoken critic of the fascists, Giacomo Matteotti, in June 1924 almost caused Mussolini’s downfall. Many suspected Mussolini’s involvement and demanded that the king remove Mussolini from power. Ignoring the national outcry, Victor Emmanuel, more fearful of a socialist takeover, threw his support behind the fascists. Mussolini survived.

For the next 18 years, Victor Emmanuel watched without undue concern as Mussolini ruled the country. Following Italy’s invasions of Ethiopia (1935-36) and Albania (1939), Victor Emmanuel was made emperor of the former and the king of the latter. Having never visited either, he renounced both titles in 1943.

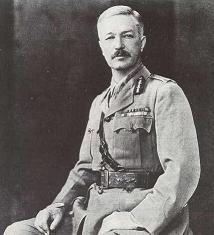

(Pictured, Victor Emmanuel III in 1936).

World War Two

Victor Emmanuel opposed Italy’s entry into the Second World War but was unable to prevent Mussolini from declaring war on France and Great Britain in June 1940. Three years later, on 24 July 1943, with Italy staring defeat in the face, the Italian Fascist Grand Council voted 19 to 8 (with three abstentions) in favour of a resolution to have Mussolini removed from power.

Victor Emmanuel opposed Italy’s entry into the Second World War but was unable to prevent Mussolini from declaring war on France and Great Britain in June 1940. Three years later, on 24 July 1943, with Italy staring defeat in the face, the Italian Fascist Grand Council voted 19 to 8 (with three abstentions) in favour of a resolution to have Mussolini removed from power.

The following day, Mussolini kept his fortnightly meeting with the king, believing that the vote the previous evening was neither constitutional nor binding. He was much mistaken. Almost apologetically, Victor Emmanuel III dismissed the 59-year-old dictator: ‘My dear Duce, it’s no longer any good. Italy has gone to bits… The soldiers don’t want to fight any more… At this moment you are the most hated man in Italy.’

With Mussolini now arrested and held in captivity, Victor Emmanuel signed the armistice with the Allies on 8 September. A month later, having fled to the town of Brindisi, he declared war on Italy’s former allies, Germany.

Princess Mafalda

The king’s daughter, Princess Mafalda, married a prominent Nazi. When her husband fell out with the Nazi regime, he was arrested and Malfalda was interned in Buchenwald concentration camp, where she died on 27 August 1944.

Republic

On 9 May 1946, a year following the end of the war, Victor Emmanuel was forced to abdicate and leave Italy. He moved to Egypt. He named his son as his successor, Umberto II, three weeks ahead of a national referendum to decide on whether Italy should maintain its monarchy. On 2 June, the nation voted 54.3 per cent in favour of becoming a republic. After 85 years, the Kingdom of Italy was at an end.

Victor Emmanuel III died in exile in Egypt on 28 December 1947, aged 78. His son, Umberto II, died in Switzerland in 1983. (Benito Mussolini, meanwhile, was executed by Italian partisans on 28 April 1945).

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

Like this:

Like Loading...

It was three years ago, May 15, that the notorious serial child killer, the Moors Murderer, Ian Brady, had died. Every UK newspaper and news channel had his 1965 mugshot on their front pages or on our screens; many column inches and many minutes of airtime were devoted to his life and his notorious, foul crimes.

It was three years ago, May 15, that the notorious serial child killer, the Moors Murderer, Ian Brady, had died. Every UK newspaper and news channel had his 1965 mugshot on their front pages or on our screens; many column inches and many minutes of airtime were devoted to his life and his notorious, foul crimes. Reginald Dyer (pictured) issued a proclamation banning any gatherings of four or more men and imposing an eight o’clock curfew. Those failing to comply risked being shot. Yet word reached Dyer that a gathering of about 5,000 men, women and children (Dyer’s estimate) had converged in a square at Jallianwala Bagh for a public meeting. The square was accessible only via a narrow gateway and otherwise was surrounded by walls. Dyer approached with a unit of about 90 soldiers, mainly Indians and Gurkhas. Although the gathering was unarmed and, it seemed, peaceful, Dyer feared that his small contingent of men would, if things got out of hand, soon be overwhelmed. Deciding attack was the best form of defence, he ordered, without warning, his men to open fire. Bedlam ensued.

Reginald Dyer (pictured) issued a proclamation banning any gatherings of four or more men and imposing an eight o’clock curfew. Those failing to comply risked being shot. Yet word reached Dyer that a gathering of about 5,000 men, women and children (Dyer’s estimate) had converged in a square at Jallianwala Bagh for a public meeting. The square was accessible only via a narrow gateway and otherwise was surrounded by walls. Dyer approached with a unit of about 90 soldiers, mainly Indians and Gurkhas. Although the gathering was unarmed and, it seemed, peaceful, Dyer feared that his small contingent of men would, if things got out of hand, soon be overwhelmed. Deciding attack was the best form of defence, he ordered, without warning, his men to open fire. Bedlam ensued. At the resultant enquiry, General Dyer was censured for ‘acting out of a mistaken concept of duty’ but survived unpunished. The British press was outraged – not by the lack of punishment but that the British establishment had failed to condone his actions. The Morning Post launched a campaign, raising over £26,000 for the beleaguered general, as they saw him; Rudyard Kipling being one such giver. Reginald Dyer quietly took early retirement and died eight years later humbled perhaps but unrepentant. Indeed, his only regret was that ‘I didn’t have time to do more’.

At the resultant enquiry, General Dyer was censured for ‘acting out of a mistaken concept of duty’ but survived unpunished. The British press was outraged – not by the lack of punishment but that the British establishment had failed to condone his actions. The Morning Post launched a campaign, raising over £26,000 for the beleaguered general, as they saw him; Rudyard Kipling being one such giver. Reginald Dyer quietly took early retirement and died eight years later humbled perhaps but unrepentant. Indeed, his only regret was that ‘I didn’t have time to do more’.

Born in Naples on 11 November 1869, the future king was so short, the German

Born in Naples on 11 November 1869, the future king was so short, the German  Victor Emmanuel opposed Italy’s entry into the Second World War

Victor Emmanuel opposed Italy’s entry into the Second World War Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. Much of India, at the time, was governed by the East India Company. The monolithic,

Much of India, at the time, was governed by the East India Company. The monolithic,  The British took refuge on the fort’s ramparts. One soldier escaped, took to his horse and galloped the sixteen miles to the garrison based

The British took refuge on the fort’s ramparts. One soldier escaped, took to his horse and galloped the sixteen miles to the garrison based

Built in Germany in 1935 the 800-foot long Zeppelin airship, the Hindenburg, was considered the height of sophisticated travel. It may only have travelled at 80 mph yet it still provided the fastest means of crossing the Atlantic – twice as fast as the speediest ship. It was akin to being on a luxury liner and had already made dozens of journeys across the Atlantic from Germany to Brazil or America and back. Of course, it wasn’t cheap – a one-way ticket across the Atlantic cost about US$400 (about US$7,000 / £4,500 in 2016).

Built in Germany in 1935 the 800-foot long Zeppelin airship, the Hindenburg, was considered the height of sophisticated travel. It may only have travelled at 80 mph yet it still provided the fastest means of crossing the Atlantic – twice as fast as the speediest ship. It was akin to being on a luxury liner and had already made dozens of journeys across the Atlantic from Germany to Brazil or America and back. Of course, it wasn’t cheap – a one-way ticket across the Atlantic cost about US$400 (about US$7,000 / £4,500 in 2016). Born 10 March 1957, Osama bin Laden was one of 52 (or more) siblings born to his billionaire father, Mohammed, and his 22 wives. Osama’s mother, Alia, was 14 when she married Mohammed, his tenth wife, and 15 when she gave birth to Osama (‘young lion’ in Arabic). Osama was the only product of this union. His parents divorced soon after his birth.

Born 10 March 1957, Osama bin Laden was one of 52 (or more) siblings born to his billionaire father, Mohammed, and his 22 wives. Osama’s mother, Alia, was 14 when she married Mohammed, his tenth wife, and 15 when she gave birth to Osama (‘young lion’ in Arabic). Osama was the only product of this union. His parents divorced soon after his birth.