On 11 November 1920, two years after the armistice that ended the First World War, the Unknown Warrior was buried in London’s Westminster Abbey in a deeply sombre ceremony that caught the mood of a nation, still reeling in grief following four years of war.

In 1916, the vicar of Margate in Kent, the Reverend David Railton (a recipient of the Military Cross) was stationed as a padre on the Western Front near the French village of Armentières on the Belgian border when he noticed a temporary grave with the inscription, ‘An Unknown British Soldier’. Moved by this simple epitaph, he initially suggested the notion to the British wartime commander-in-chief, Sir Douglas Haig that one fallen man, unknown in name or rank, should represent all those who died during the war who had no known grave. In August 1920, having received no response from Haig, Railton muted the idea to Herbert Ryle, the Dean of Westminster, who, in turn, passed it onto Buckingham Palace.

Initially, the king, George V (pictured), was not enthusiastic about the proposal; not wanting to re-open the healing wound of national grief but was persuaded into the idea by the prime minister, David Lloyd-George.

Initially, the king, George V (pictured), was not enthusiastic about the proposal; not wanting to re-open the healing wound of national grief but was persuaded into the idea by the prime minister, David Lloyd-George.

On 7 November 1920, the remains of six (some sources state four) unidentified British soldiers were exhumed – one each from six different battlefields (Aisne, Arras, Cambrai, Marne, Somme and Ypres). The six corpses were transported to a chapel in the village of St Pol, near Ypres, where they were each laid out on a stretcher and covered by the Union flag. There, in the company of a padre (not Rev Railton), a blindfolded officer entered the chapel and touched one of the bodies.

The following morning, chaplains of the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church and Non-Conformist churches held a service for the chosen soldier. Placed in a plain coffin, the Unknown Warrior was taken back on a train to England via Boulogne. At Boulogne, the coffin was kept overnight in the town’s castle, a guard of honour keeping vigil.

A British Warrior

On the morning of the 9 November, the coffin was placed in a larger casket made from wood, three inches thick, taken from an oak tree in the gardens of London’s Hampton Court Palace. Mounted on the side of the coffin, a 16th-century sword from the collection at the Tower of London especially chosen by George V. Draped over the casket, the Union flag, which had been used by Rev Railton as an altar cloth during the war. (The flag, known as the Padre’s Flag, now hangs in St George’s Chapel within Westminster Abbey). The coffin plate bore the inscription: ‘A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country’.

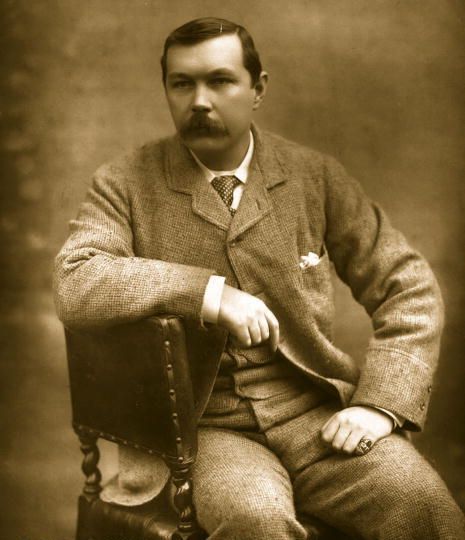

A staunch republican and troublemaker, like his father, Georges Clemenceau was once imprisoned for 73 days (some sources state 77 days) by Napoleon III’s government for publishing a republican newspaper and trying to incite demonstrations against the monarchy. In 1865, fearing another arrest, and possible incarceration on Devil’s Island, Clemenceau fled to the US, arriving towards the end of the American Civil War. He lived first in New York, where he worked as a journalist, and then in Connecticut where he became a teacher in a private girls’ school. Clemenceau married one of his American students, Mary Plummer, and together they had three children before divorcing seven years later. (Of his son, Clemenceau, known for his wit, said, ‘If he had not become a Communist at 22, I would have disowned him. If he is still a Communist at 30, I will do it then.’)

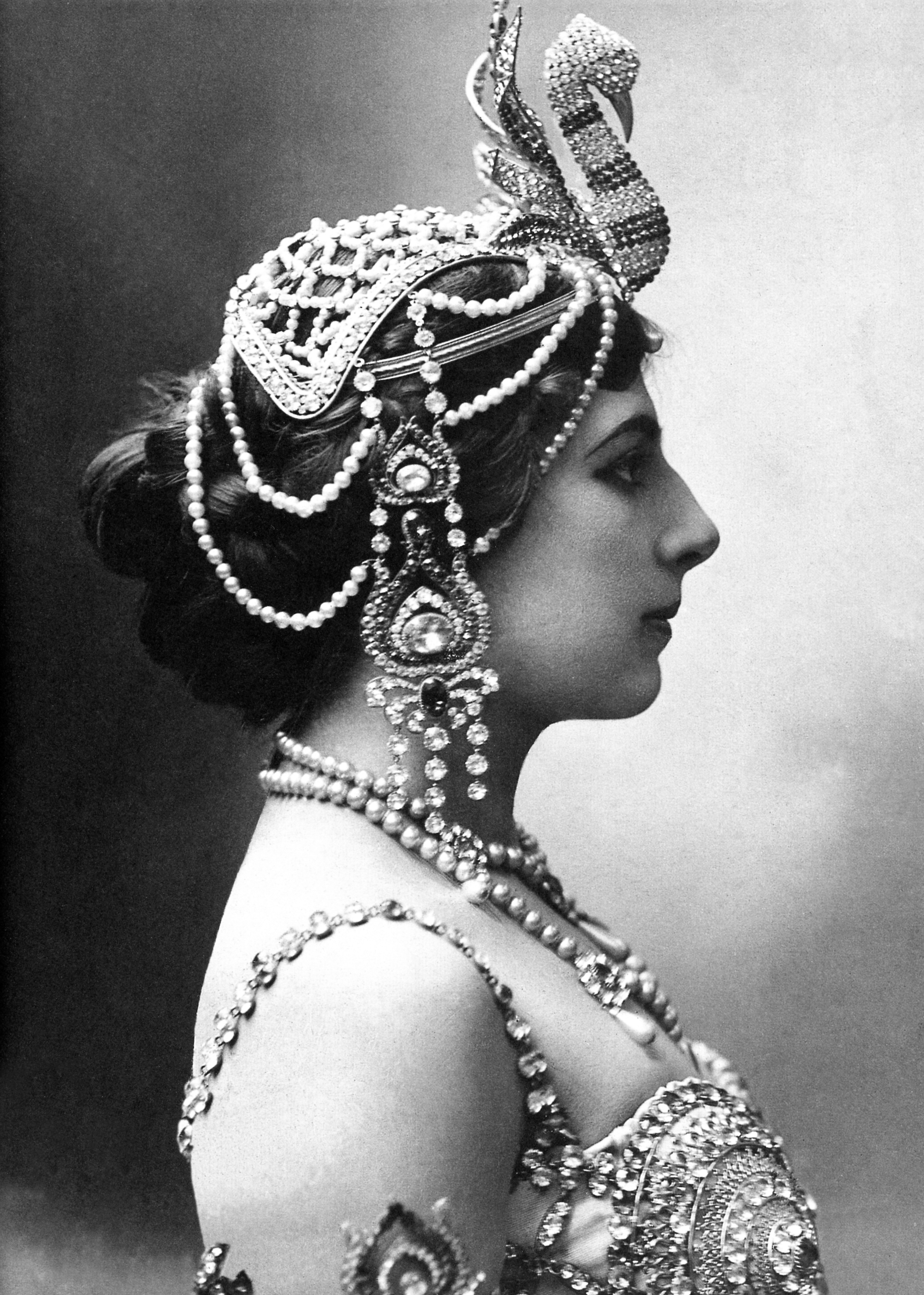

A staunch republican and troublemaker, like his father, Georges Clemenceau was once imprisoned for 73 days (some sources state 77 days) by Napoleon III’s government for publishing a republican newspaper and trying to incite demonstrations against the monarchy. In 1865, fearing another arrest, and possible incarceration on Devil’s Island, Clemenceau fled to the US, arriving towards the end of the American Civil War. He lived first in New York, where he worked as a journalist, and then in Connecticut where he became a teacher in a private girls’ school. Clemenceau married one of his American students, Mary Plummer, and together they had three children before divorcing seven years later. (Of his son, Clemenceau, known for his wit, said, ‘If he had not become a Communist at 22, I would have disowned him. If he is still a Communist at 30, I will do it then.’) Born 7 August 1876 to a wealthy Dutch family, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married within three months of meeting each other and in 1895 moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children.

Born 7 August 1876 to a wealthy Dutch family, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married within three months of meeting each other and in 1895 moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children. Returning to Paris,

Returning to Paris,  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. It started with the usual preliminary bombardment. Lasting seven days, and involving 1,350 guns and 52,000 tonnes of explosives fired onto the German lines, British soldiers were assured that the 18-mile German

It started with the usual preliminary bombardment. Lasting seven days, and involving 1,350 guns and 52,000 tonnes of explosives fired onto the German lines, British soldiers were assured that the 18-mile German  At 7.20 am on

At 7.20 am on  On 14 July, following a partially successful nighttime attack, the British sent in the cavalry – a rare sight on the Western Front of World War One and one that stirred the romantic notions in old timers such as Haig. But the horses became bogged down in the mud, the Germans opened

On 14 July, following a partially successful nighttime attack, the British sent in the cavalry – a rare sight on the Western Front of World War One and one that stirred the romantic notions in old timers such as Haig. But the horses became bogged down in the mud, the Germans opened

Born 24 June 1850 in County Kerry, Ireland, Horatio Kitchener first saw active service with the French army during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and, a decade later, with the British Army during the occupation of Egypt. He was part of the force that tried, unsuccessfully, to relieve General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum in 1885. The death of Gordon, at the hands of Mahdist forces, caused great anguish in Britain. Thirteen years later, as commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, Kitchener led the campaign of reprisal into Sudan, defeating the Mahdists at the Battle of Omdurman and reoccupying Khartoum in 1898. Kitchener had restored Britain’s pride.

Born 24 June 1850 in County Kerry, Ireland, Horatio Kitchener first saw active service with the French army during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and, a decade later, with the British Army during the occupation of Egypt. He was part of the force that tried, unsuccessfully, to relieve General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum in 1885. The death of Gordon, at the hands of Mahdist forces, caused great anguish in Britain. Thirteen years later, as commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, Kitchener led the campaign of reprisal into Sudan, defeating the Mahdists at the Battle of Omdurman and reoccupying Khartoum in 1898. Kitchener had restored Britain’s pride.

In India French first met his future rival,

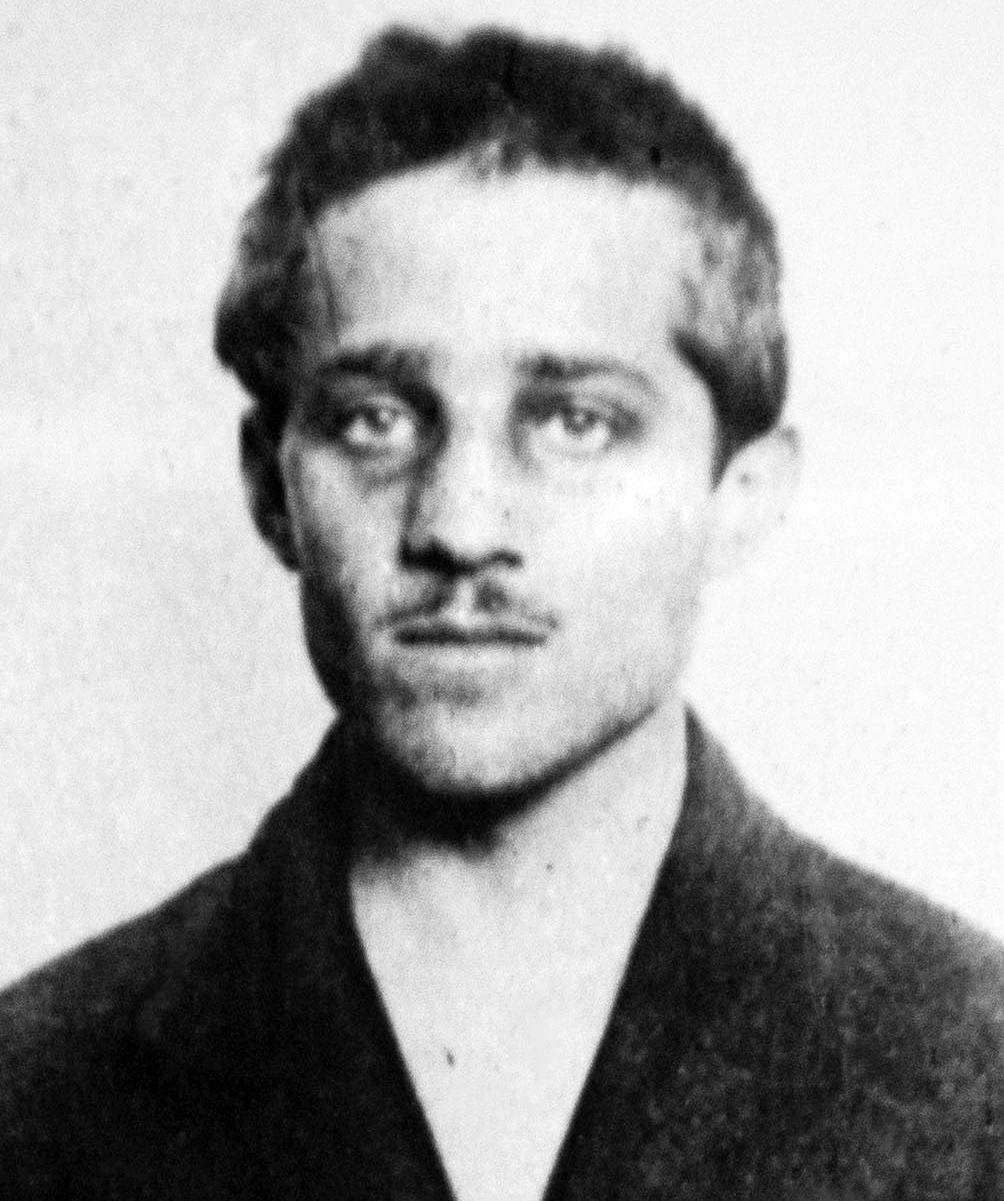

In India French first met his future rival,  Thomas Highgate was born in Shoreham in Kent on 13 May 1895. In February 1913, aged 17, he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. Within months, Highgate fell foul of the military authorities – in 1913, he

Thomas Highgate was born in Shoreham in Kent on 13 May 1895. In February 1913, aged 17, he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. Within months, Highgate fell foul of the military authorities – in 1913, he  Shoreham

Shoreham Rupert Colley.

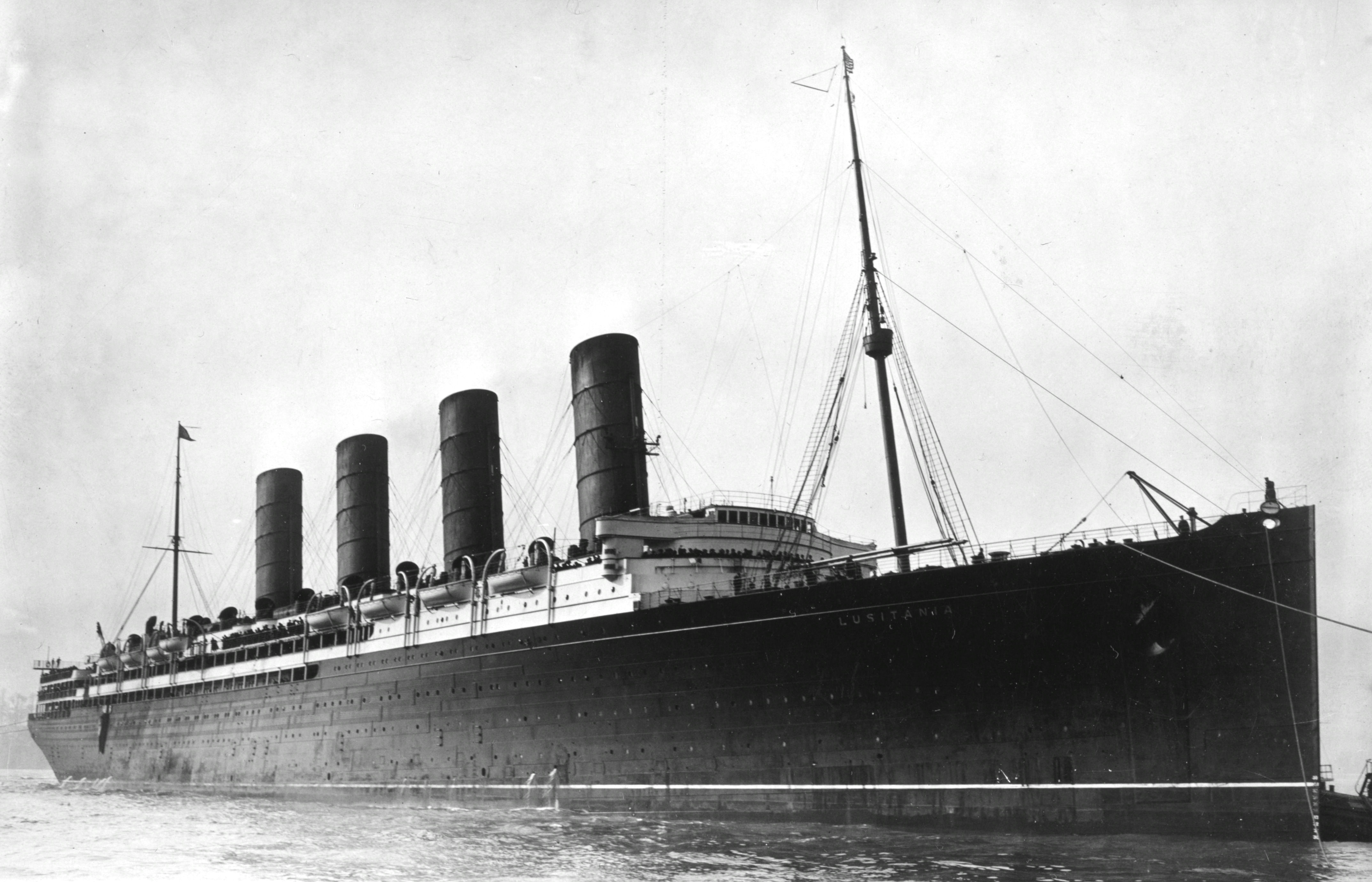

Rupert Colley. The ‘Great War’ was still less than a year old. On 18 February 1915, in response to Great Britain’s blockade of Germany, the Germans announced that it would, in future, be operating a policy of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. In other words, German U-boats would actively seek out and attack enemy shipping within the war zone of British waters. Even ships displaying a neutral flag, they announced, would be at risk – the Germans

The ‘Great War’ was still less than a year old. On 18 February 1915, in response to Great Britain’s blockade of Germany, the Germans announced that it would, in future, be operating a policy of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. In other words, German U-boats would actively seek out and attack enemy shipping within the war zone of British waters. Even ships displaying a neutral flag, they announced, would be at risk – the Germans  Wealthy passengers boarding the Lusitania, a 32,000-ton luxury Cunard liner, in New York saw an advertisement issued by the US German embassy warning them of the risk:

Wealthy passengers boarding the Lusitania, a 32,000-ton luxury Cunard liner, in New York saw an advertisement issued by the US German embassy warning them of the risk: