On 22 June 1941, Adolf Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. What followed was a war of annihilation, a horrific clash of totalitarianism, and the most destructive war in history.

Hitler’s intention was always to invade the Soviet Union. It was, along with the destruction of the Jews, fundamental to his core objectives – living space in the east and the subjugation of the Slavic race. He stated his intentions clearly enough in his semi-autobiographical Mein Kampf, published in 1925. This was meant to be a war of obliteration – and despite the vastness of Russian territory and manpower, Hitler anticipated a quick victory (his generals were predicting ten weeks). So confident the Nazi hierarchy, that they provided their troops with summer uniforms but made no provision for the fierce Russian winter that lay further ahead.

Unprecedented, unmerciful, unrelenting

“You have only to kick in the door,” said Hitler confidently, “and the whole rotten  structure will come crashing down.” Two tons of Iron Crosses were waiting in Germany for those involved with the capture of Moscow. This was always going to be the most brutal war, one which could not be “conducted with chivalry,” as Hitler told his generals, but “conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful, unrelenting harshness.”

structure will come crashing down.” Two tons of Iron Crosses were waiting in Germany for those involved with the capture of Moscow. This was always going to be the most brutal war, one which could not be “conducted with chivalry,” as Hitler told his generals, but “conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful, unrelenting harshness.”

Two years earlier, on 23 August 1939, the Nazis and Soviets had signed a non-aggression pact. But both sides knew it was never more than a postponement of hostilities. For the Soviets, it gave them time to build up their defences (in the event little was achieved); and for Hitler, the pact gave him time to concentrate on the West (the defeat of France, Britain and elsewhere) before turning his attention eastwards.

May God Bless Our Weapons

Now, in June 1941, with his Western objectives achieved (with the exception of Britain), the time had come.

On the eve of attack, Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister for Propaganda, wrote in his diary, “One can hear the breath of history… May God bless our weapons!”

Stalin’s spies had forewarned him time and again of the expected attack but he refused to believe it, dismissing it all as ‘Hitler’s bluff’. When warned of the imminent German invasion by a high-ranking Luftwaffe spy, Stalin responded, ‘Tell your “source” to go fuck his mother.’ He ordered another shot for spreading ‘misinformation’.

Stalin strenuously forbade anything that might appear provocative to the Germans, even insisting on the continuation of Russian food and metal exports to the Germans, as agreed in the Pact. He prohibited the evacuation of people living near the German border and forbade the setting up of defences.

So when, at 4 a.m. on 22 June 1941, Operation Barbarossa was launched, progress was rapid. (Barbarossa was the nickname given to Frederick I, 1122-1190, king of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor). At first, more frightened of Stalin’s prohibition of ‘provocative’ acts than the German armies, Soviet soldiers didn’t dare fire back. When one desperate Soviet border guard signalled, ‘We’re being fired on. What do we do?’, the response came back, ‘You must be mad; and why isn’t your signal in code?’

(22 June was not the most auspicious date on which to launch an attack on the Soviet Union. It was on 22 June, exactly 129 years before, that Napoleon started his ill-fated invasion of Russia.)

For the good of humanity

Operation Barbarossa was the largest attack ever staged – three and a half million Axis troops, including Romanian and Hungarian, along a 900-mile front from Finland in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The Germans employed their Blitzkrieg, or lightning attacks, that had proved so successful against Poland and France. Their tanks were advancing 50 miles a day and, within the first day, one-quarter of the Soviet Union’s air strength had been destroyed – the Russians had left rows of uncamouflaged planes sitting on their airfields, providing easy targets for the Luftwaffe.

Operation Barbarossa was the largest attack ever staged – three and a half million Axis troops, including Romanian and Hungarian, along a 900-mile front from Finland in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The Germans employed their Blitzkrieg, or lightning attacks, that had proved so successful against Poland and France. Their tanks were advancing 50 miles a day and, within the first day, one-quarter of the Soviet Union’s air strength had been destroyed – the Russians had left rows of uncamouflaged planes sitting on their airfields, providing easy targets for the Luftwaffe.

German soldiers were excited by the prospect of defeating Stalin’s mighty Bolshevik empire. One 18-year-old German tank driver wrote, ‘It’s a German’s duty for the good of humanity to impose our way of life on lower races and nations.’ They, like Hitler, expected an easy victory. An SS sergeant wrote, “My conviction is that Russia’s destruction will take no longer than France’s; I assume I’ll still get my leave in August.”

By the end of October, Moscow was only 65 miles away; over 500,000 square miles of Soviet territory had been captured and, as well as huge numbers of Soviet troops and civilians killed, 3 million Red Army soldiers had been taken prisoner of war, where, unlike in the West, the rules of captivity held no meaning for the Germans. (Of the five million Soviet PoWs taken during the course of the war, 3½ million were to die of malnutrition, disease and brutality. Those who survived returned home to the Soviet Union to be immediately branded as traitors and, in many instances, sent to the gulag.).

By the end of October, Moscow was only 65 miles away; over 500,000 square miles of Soviet territory had been captured and, as well as huge numbers of Soviet troops and civilians killed, 3 million Red Army soldiers had been taken prisoner of war, where, unlike in the West, the rules of captivity held no meaning for the Germans. (Of the five million Soviet PoWs taken during the course of the war, 3½ million were to die of malnutrition, disease and brutality. Those who survived returned home to the Soviet Union to be immediately branded as traitors and, in many instances, sent to the gulag.).

Stalin, once his generals had persuaded him that his country was under attack, controlled the Soviet response. His first acts were to order the execution of those who retreated and to send Vyacheslav Molotov, his foreign minister, to formally announce the war to his people. Molotov’s radio broadcast, relayed across cities by loudspeaker, announced this “act of treachery unprecedented in the history of civilised nations.”

The Great Patriotic War

Stalin attempted to control every aspect of operations but only for the first week before suddenly giving up. “Lenin founded our state,” he declared, exhausted, “and we’ve fucked it up.” This “bag of bones in a grey tunic”, as Nikita Khrushchev later described him, disappeared to his dacha where, many believe, he suffered a mental breakdown. Nothing could be done without him, nothing issued in the way of direction.

When, after three days, his Politburo came for him, Stalin feared he was about to be arrested. Instead, they came to ask him what to do. Once stirred, Stalin re-emerged. On 3 July, in his first public address since the invasion, perhaps the most important speech of his life, Stalin spoke of “The Great Patriotic War”.

By the end of June, Finland, Hungary and Albania had all declared war on the USSR. For Finland, it was a ‘holy war’, an opportunity to avenge their defeat the previous year during the Finnish-Soviet ‘Winter War’.

The sides had been drawn, the invasion launched. What followed was the most ferocious war ever known which was to last three years and claim the lives of over five million Axis troops, nine million Soviet troops, and up to 20 million civilian deaths.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

A fervent supporter of Hitler, 36-year-old Count Claus von Stauffenberg had fought bravely during the Second World War for the Fuhrer. Fighting in Tunisia in 1943, Stauffenberg was badly wounded, losing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers of his left. Once recovered, Stauffenberg was transferred to the Eastern Front where he witnessed the atrocities firsthand which made him question his loyalty. As it became increasingly apparent that Germany would not win the war, Stauffenberg lost faith in Hitler and the Nazi cause.

A fervent supporter of Hitler, 36-year-old Count Claus von Stauffenberg had fought bravely during the Second World War for the Fuhrer. Fighting in Tunisia in 1943, Stauffenberg was badly wounded, losing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers of his left. Once recovered, Stauffenberg was transferred to the Eastern Front where he witnessed the atrocities firsthand which made him question his loyalty. As it became increasingly apparent that Germany would not win the war, Stauffenberg lost faith in Hitler and the Nazi cause. Born 18 July 1887, Vidkun Quisling’s life and early career had started promisingly. As a child, the son of a Lutheran pastor, he was considered somewhat a mathematical child prodigy and, as a young cadet coming out of military school, he gained the highest recorded marks in Norway.

Born 18 July 1887, Vidkun Quisling’s life and early career had started promisingly. As a child, the son of a Lutheran pastor, he was considered somewhat a mathematical child prodigy and, as a young cadet coming out of military school, he gained the highest recorded marks in Norway. With no support and no influence, Quisling looked destined to wither away into obscurity. But in Adolf Hitler, whom Quisling visited in December 1939, he had a friend.

With no support and no influence, Quisling looked destined to wither away into obscurity. But in Adolf Hitler, whom Quisling visited in December 1939, he had a friend.

Vera

Vera  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

On 23 August 1939, the Nazis and Soviets had signed a non-aggression pact. But both sides knew it was never meant to be more than a postponement of hostilities.

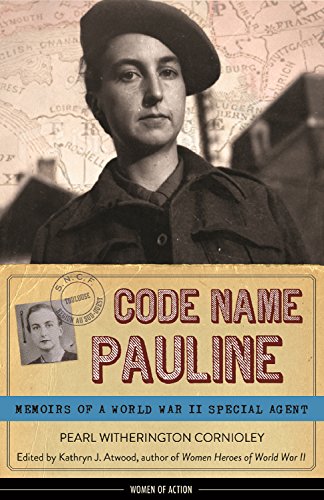

On 23 August 1939, the Nazis and Soviets had signed a non-aggression pact. But both sides knew it was never meant to be more than a postponement of hostilities. Pearl’s father was a drifter and an alcoholic, rarely at home. Although she states she was “never unhappy at home with Mummy”, it was, nonetheless, a difficult childhood, having to bear her parents’ arguing, often rummaging for food and fighting off her father’s debt collectors. As the eldest of four girls and with an English mother who found it hard to cope with life in Paris, Pearl was imbued from an early age with a sense of responsibility; a responsibility that deprived her of a proper childhood. As soon as she was old enough, and following her father’s death, Pearl went out to work to earn money, not for herself, but her mother and her sisters.

Pearl’s father was a drifter and an alcoholic, rarely at home. Although she states she was “never unhappy at home with Mummy”, it was, nonetheless, a difficult childhood, having to bear her parents’ arguing, often rummaging for food and fighting off her father’s debt collectors. As the eldest of four girls and with an English mother who found it hard to cope with life in Paris, Pearl was imbued from an early age with a sense of responsibility; a responsibility that deprived her of a proper childhood. As soon as she was old enough, and following her father’s death, Pearl went out to work to earn money, not for herself, but her mother and her sisters. structure will come crashing down.” Two tons of Iron Crosses were waiting in Germany for those involved with the capture of Moscow. This was always going to be the most brutal war, one which could not be “conducted with chivalry,” as Hitler told his generals, but “conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful, unrelenting harshness.”

structure will come crashing down.” Two tons of Iron Crosses were waiting in Germany for those involved with the capture of Moscow. This was always going to be the most brutal war, one which could not be “conducted with chivalry,” as Hitler told his generals, but “conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful, unrelenting harshness.” Operation Barbarossa was the largest attack ever staged – three and a half million Axis troops, including Romanian and Hungarian, along a 900-mile front from Finland in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The Germans employed their Blitzkrieg, or lightning attacks, that had proved so successful against Poland and France. Their tanks were advancing 50 miles a day and, within the first day, one-quarter of the Soviet Union’s air strength had been destroyed – the Russians had left rows of

Operation Barbarossa was the largest attack ever staged – three and a half million Axis troops, including Romanian and Hungarian, along a 900-mile front from Finland in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The Germans employed their Blitzkrieg, or lightning attacks, that had proved so successful against Poland and France. Their tanks were advancing 50 miles a day and, within the first day, one-quarter of the Soviet Union’s air strength had been destroyed – the Russians had left rows of  By the end of October, Moscow was only 65 miles away; over 500,000 square miles of Soviet territory had been captured and, as well as huge numbers of Soviet troops and civilians killed, 3 million Red Army soldiers had been taken prisoner of war, where, unlike in the West, the rules of

By the end of October, Moscow was only 65 miles away; over 500,000 square miles of Soviet territory had been captured and, as well as huge numbers of Soviet troops and civilians killed, 3 million Red Army soldiers had been taken prisoner of war, where, unlike in the West, the rules of  Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. On 22 June 1940, Hitler, now the German Führer, got his revenge – it was the turn of the French to surrender, and Hitler made sure that it was done in the most demeaning circumstances possible – in exactly the same carriage and in the same spot as the signing twenty-two years earlier.

On 22 June 1940, Hitler, now the German Führer, got his revenge – it was the turn of the French to surrender, and Hitler made sure that it was done in the most demeaning circumstances possible – in exactly the same carriage and in the same spot as the signing twenty-two years earlier. Here, below, is a brief resume

Here, below, is a brief resume