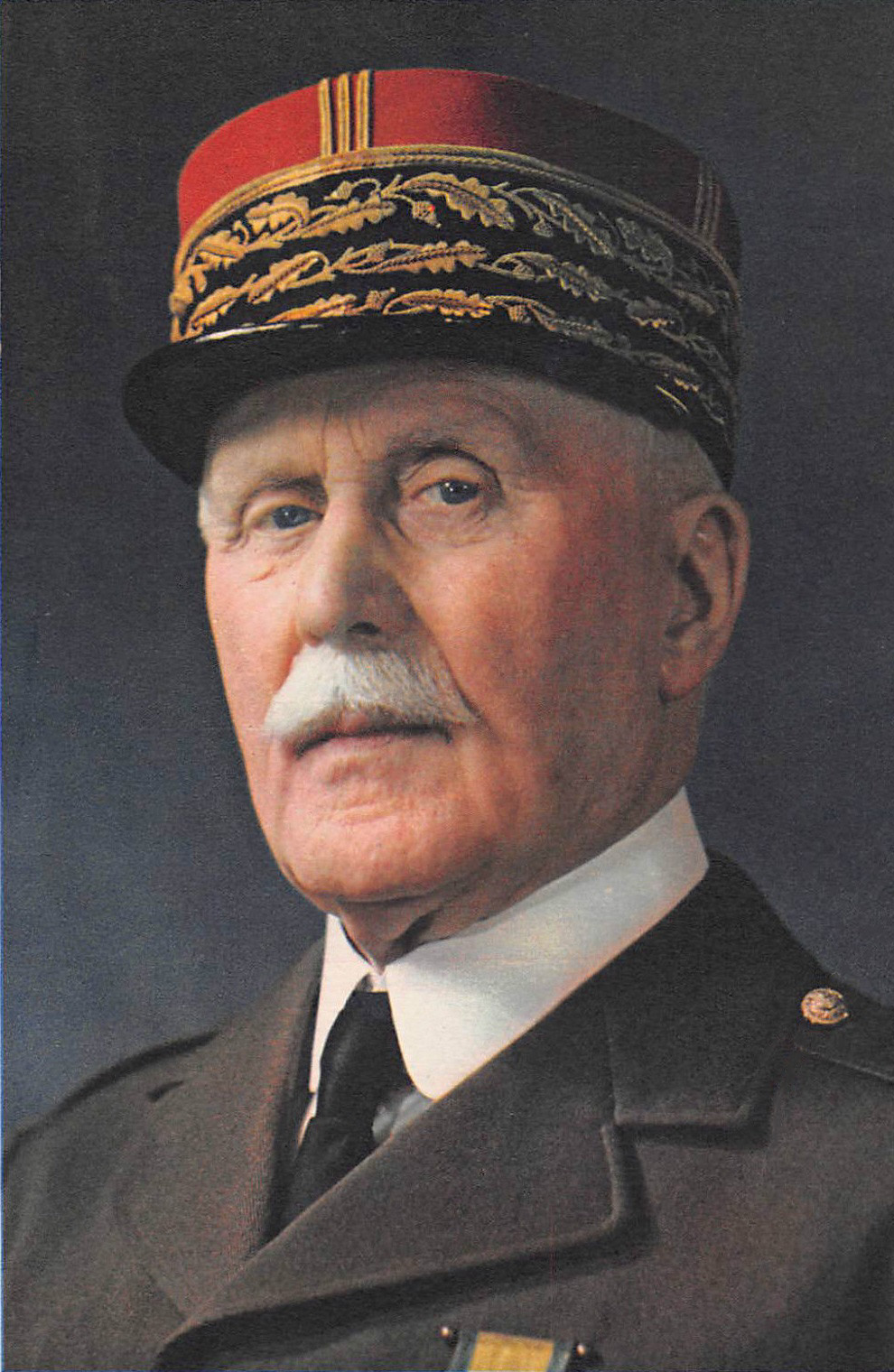

Few men over the last century can have experienced such a change of fortune as Philippe Pétain. During the First World War, Pétain was hailed as the ‘Saviour of Verdun’, helping the French keep the Germans at bay during the 1916 Battle of Verdun. In May 1917 he was made commander-in-chief of French forces. His first task was to quell the French mutiny, which he did through a mixture of discipline and reform.

Pétain’s popularity improved even further when he limited French offensives to the minimum, claiming he was waiting for ‘the tanks and the Americans’.

Pétain and World War Two

World War Two and on 10 May 1940 Hitler’s troops invaded France. A month later, having swept aside French resistance and dispatched the British forces at Dunkirk, the swastika was flying over the Arc du Triomphe.

France surrenders

On 17 June, the French prime minister, Paul Reynaud, resigned, to be replaced by the 84-year-old Philippe Pétain. Pétain’s first acts were to seek an armistice with the Germans and order Reynaud’s arrest. On 22 June, 50 miles north-east of Paris, the French officially surrendered, the ceremony taking place in the same spot and in the same railway carriage that the Germans had surrendered to the French on 11 November 1918.

Northern France, as dictated by the terms of the surrender, would be occupied by the Germans, whilst southern France, 40 per cent of the country, would remain nominally independent with its own government based in the spa town of Vichy in central France, 200 miles south of Paris. Pétain would be its Head of State. A small corner of south-easternFrance, around Nice, was entrusted to Italian control; Italy having entered the war on the 10 June.

Pétain and Vichy France had the support of much of the nation. The French considered the British evacuation at Dunkirk as nothing less than a betrayal, and many labelled General Charles de Gaulle, who had escaped France to begin his life of exile in London, a traitor. Indeed, he was later sentenced to death – in absentia by the Vichy government.

The end of democracy

On 10 July 1940, the French Chamber of Deputies transferred all its powers to Pétain, dissolving the Third Republic and thus doing away with democracy, the French Parliament and itself. Philippe Pétain, never a fan of democracy, which he regarded as a weak institution, was delighted. Strong, central government was Pétain’s way, and relishing his new role in Vichy’s Hotel du Pac, Pétain immediately set about decreeing swathes of new legislation, much of it anti-Semitic, and becoming the most authoritative French head of state since Napoleon.

On 15 April 1942, Malta received Britain’s highest civilian award for gallantry, the George Cross. But why would an island receive a medal?

On 15 April 1942, Malta received Britain’s highest civilian award for gallantry, the George Cross. But why would an island receive a medal? The Germans decided that Malta was causing too much damage and Albert Kesselring, Hitler’s Mediterranean commander, promised to “wipe Malta off the map.” Luftwaffe and U-boats stationed sixty miles north on the island of Sicily launched aerial attacks on Malta and the siege intensified. Supplies to the island virtually ceased and the inhabitants suffered eighteen months of hunger as well as continual bombardment. Civilians, starved and frightened, packed the caves beneath the capital Valletta.

The Germans decided that Malta was causing too much damage and Albert Kesselring, Hitler’s Mediterranean commander, promised to “wipe Malta off the map.” Luftwaffe and U-boats stationed sixty miles north on the island of Sicily launched aerial attacks on Malta and the siege intensified. Supplies to the island virtually ceased and the inhabitants suffered eighteen months of hunger as well as continual bombardment. Civilians, starved and frightened, packed the caves beneath the capital Valletta. Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

The early death of his wife in 1937 from

The early death of his wife in 1937 from  brought up in a middle-class Lutheran environment. (Eichmann kept his faith right up to the late 1930s, long after it was fashionable for Nazis to denounce religion).

brought up in a middle-class Lutheran environment. (Eichmann kept his faith right up to the late 1930s, long after it was fashionable for Nazis to denounce religion).

The photograph sums it up: General Arthur Percival (far right), the British commander in Malaya, and his fellow officers, walking forlornly towards the Japanese commanders to sign the dismal surrender. With their baggy shorts, knee-length socks and tin helmets, one carries the Union Jack while another holds the white flag of surrender. Escorting them, a number of Japanese soldiers, or ‘little men’ as the British military elite referred to them.

The photograph sums it up: General Arthur Percival (far right), the British commander in Malaya, and his fellow officers, walking forlornly towards the Japanese commanders to sign the dismal surrender. With their baggy shorts, knee-length socks and tin helmets, one carries the Union Jack while another holds the white flag of surrender. Escorting them, a number of Japanese soldiers, or ‘little men’ as the British military elite referred to them. Born in Barcelona on 14 February 1912, Pujol was working on a chicken farm when, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. He managed to fight for both the Republican side and the Nationalists. He was committed to neither and hated the extreme views they each represented. By the end of the war, he was able to claim that he had served in both armies without firing a single bullet for either.

Born in Barcelona on 14 February 1912, Pujol was working on a chicken farm when, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. He managed to fight for both the Republican side and the Nationalists. He was committed to neither and hated the extreme views they each represented. By the end of the war, he was able to claim that he had served in both armies without firing a single bullet for either. Germany’s seventh largest city, 100 miles southeast of Berlin, Dresden was known as the ‘Florence of the Elbe’, such was its architectural splendour, its large collections of art and quaint timbered buildings. In February 1945, the city’s population had temporarily been inflated by a huge influx of German refugees, perhaps up to 350,000, fleeing the Soviet advance sixty miles away to the east.

Germany’s seventh largest city, 100 miles southeast of Berlin, Dresden was known as the ‘Florence of the Elbe’, such was its architectural splendour, its large collections of art and quaint timbered buildings. In February 1945, the city’s population had temporarily been inflated by a huge influx of German refugees, perhaps up to 350,000, fleeing the Soviet advance sixty miles away to the east.