On 4 June 1942, the Nazi wartime leader of occupied Czechoslovakia, Reinhard Heydrich, died. He had been the victim of an assassination attempt a week earlier. Aged 38, the ‘Butcher of Prague’ was dead.

Six months earlier, on 28 December 1941, two Free Czech agents, Jan Kubis and Jozef Gabčík, trained by Britain’s Special Operations Executive (the SOE), had parachuted into Czechoslovakia. Their objective, almost certain to end in their deaths, was to assassinate the ‘Deputy Reich Protector of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia’, to give Reinhard Heydrich his full title.

Assassination attempt

On 27 May 1942, the agents, on learning of Heydrich’s movements that day, went into action. As the car taking Heydrich to a meeting slowed to navigate a hairpin bend, the two men attacked. Heydrich, as was his routine, was without an armed escort. Gabčík tried to shoot Heydrich but his submachine gun jammed at the fatal moment. Instead of ordering his chauffeur to drive off, Heydrich chose to fight. He attempted to fire back but a small bomb, thrown by Kubis, exploded, injuring him. Heydrich and his driver gave chase on foot, but the two agents escaped before Heydrich, bleeding profusely, collapsed from his injuries. He was rushed to hospital. Surgeons operated and initially it seemed the stricken Nazi was recovering.

On 27 May 1942, the agents, on learning of Heydrich’s movements that day, went into action. As the car taking Heydrich to a meeting slowed to navigate a hairpin bend, the two men attacked. Heydrich, as was his routine, was without an armed escort. Gabčík tried to shoot Heydrich but his submachine gun jammed at the fatal moment. Instead of ordering his chauffeur to drive off, Heydrich chose to fight. He attempted to fire back but a small bomb, thrown by Kubis, exploded, injuring him. Heydrich and his driver gave chase on foot, but the two agents escaped before Heydrich, bleeding profusely, collapsed from his injuries. He was rushed to hospital. Surgeons operated and initially it seemed the stricken Nazi was recovering.

On 2 June, a week after the attack, he received a visit from his superior and mentor, Heinrich Himmler. Following Himmler’s visit, Heydrich slipped into a coma and died on 4 June. He was given a sumptuous funeral in Prague followed by a second ceremony in Berlin.

Meanwhile, Heydrich’s assassins, Kubis and Gabčík, hid in the crypt of a Prague church. Three weeks later they were betrayed and the church was surrounded by 800 members of the SS. The men held out for as long as possible before turning their guns on themselves.

Young Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich was born in the eastern German town of Halle on 7 March 1904. His mother was an actress and his father, Richard, a music teacher and occasional opera composer inducing in his sons (Reinhard and his younger brother, Heinz) a love of the operas of Richard Wagner. Reinhard became an accomplished violinist. Heydrich’s father, a fervent German nationalist, was sometimes known as Heydrich-Süss. Süss, having a Jewish ring to it, fuelled rumours that the family had Jewish blood. Later, Reinhard Heydrich was so haunted by the thought, that he ordered an SS investigation into his family ancestry. The report concluded, unsurprisingly, that Reinhard Heydrich’s family contained no trace of Jewish descent. Continue reading

In his latter years, Stalin’s health had deteriorated and towards the end of 1952 he suffered several blackouts and losses of memory. His sense of paranoia had reached absurd proportions. “I’m finished”, he said in his final days, “I don’t even trust myself.”

In his latter years, Stalin’s health had deteriorated and towards the end of 1952 he suffered several blackouts and losses of memory. His sense of paranoia had reached absurd proportions. “I’m finished”, he said in his final days, “I don’t even trust myself.” Peters’ arrival in the US in 1967 (pictured) gave the West a huge propaganda coup – the defection of Stalin’s own daughter was the ultimate proof of how terrible life was behind the Iron Curtain. She had even been prepared to leave behind her two adult children, aged 22 and 17, in the Soviet Union.

Peters’ arrival in the US in 1967 (pictured) gave the West a huge propaganda coup – the defection of Stalin’s own daughter was the ultimate proof of how terrible life was behind the Iron Curtain. She had even been prepared to leave behind her two adult children, aged 22 and 17, in the Soviet Union. Having been devoted to the

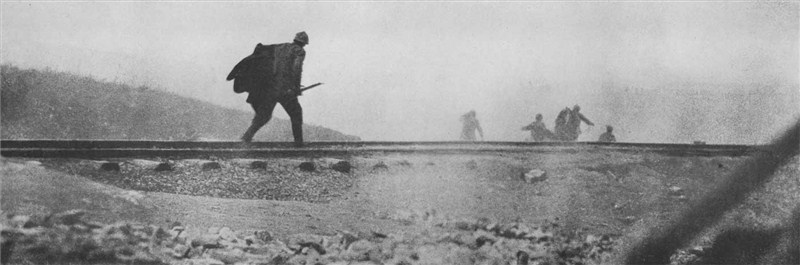

Having been devoted to the  An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’.

An ancient town, Verdun in northeastern France, was, in 1915, surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began. 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, which held a symbolic tradition among the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joseph Joffre, the French commander, was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit. Waking Joffre from his slumber, Briand insisted that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat – but everyone else will’. In 1931, Malcolm’s father died in mysterious circumstances, run over by a streetcar. Although it was never proved, the suspicion remained that he had been killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan. The police recorded the death as suicide, thereby annulling Earl Little’s life insurance.

In 1931, Malcolm’s father died in mysterious circumstances, run over by a streetcar. Although it was never proved, the suspicion remained that he had been killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan. The police recorded the death as suicide, thereby annulling Earl Little’s life insurance. The photograph sums it up: General Arthur Percival (far right), the British commander in Malaya, and his fellow officers, walking forlornly towards the Japanese commanders to sign the dismal surrender. With their baggy shorts, knee-length socks and tin helmets, one carries the Union Jack while another holds the white flag of surrender. Escorting them, a number of Japanese soldiers, or ‘little men’ as the British military elite referred to them.

The photograph sums it up: General Arthur Percival (far right), the British commander in Malaya, and his fellow officers, walking forlornly towards the Japanese commanders to sign the dismal surrender. With their baggy shorts, knee-length socks and tin helmets, one carries the Union Jack while another holds the white flag of surrender. Escorting them, a number of Japanese soldiers, or ‘little men’ as the British military elite referred to them. Born in Barcelona on 14 February 1912, Pujol was working on a chicken farm when, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. He managed to fight for both the Republican side and the Nationalists. He was committed to neither and hated the extreme views they each represented. By the end of the war, he was able to claim that he had served in both armies without firing a single bullet for either.

Born in Barcelona on 14 February 1912, Pujol was working on a chicken farm when, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. He managed to fight for both the Republican side and the Nationalists. He was committed to neither and hated the extreme views they each represented. By the end of the war, he was able to claim that he had served in both armies without firing a single bullet for either. Germany’s seventh largest city, 100 miles southeast of Berlin, Dresden was known as the ‘Florence of the Elbe’, such was its architectural splendour, its large collections of art and quaint timbered buildings. In February 1945, the city’s population had temporarily been inflated by a huge influx of German refugees, perhaps up to 350,000, fleeing the Soviet advance sixty miles away to the east.

Germany’s seventh largest city, 100 miles southeast of Berlin, Dresden was known as the ‘Florence of the Elbe’, such was its architectural splendour, its large collections of art and quaint timbered buildings. In February 1945, the city’s population had temporarily been inflated by a huge influx of German refugees, perhaps up to 350,000, fleeing the Soviet advance sixty miles away to the east.