On Sunday 13 April 1919, the occupants of the city of Amritsar in Punjab were preparing to celebrate the Sikh New Year. Three days previously, six Britons had been indiscriminately killed by an Indian mob and the British, fearful of further violence during such a potentially volatile occasion, sent in a man ‘not afraid to act.’ That man was 54-year-old Reginald Dyer, and act he did.

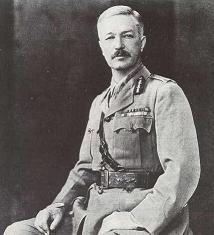

Reginald Dyer (pictured) issued a proclamation banning any gatherings of four or more men and imposing an eight o’clock curfew. Those failing to comply risked being shot. Yet word reached Dyer that a gathering of about 5,000 men, women and children (Dyer’s estimate) had converged in a square at Jallianwala Bagh for a public meeting. The square was accessible only via a narrow gateway and otherwise was surrounded by walls. Dyer approached with a unit of about 90 soldiers, mainly Indians and Gurkhas. Although the gathering was unarmed and, it seemed, peaceful, Dyer feared that his small contingent of men would, if things got out of hand, soon be overwhelmed. Deciding attack was the best form of defence, he ordered, without warning, his men to open fire. Bedlam ensued.

Reginald Dyer (pictured) issued a proclamation banning any gatherings of four or more men and imposing an eight o’clock curfew. Those failing to comply risked being shot. Yet word reached Dyer that a gathering of about 5,000 men, women and children (Dyer’s estimate) had converged in a square at Jallianwala Bagh for a public meeting. The square was accessible only via a narrow gateway and otherwise was surrounded by walls. Dyer approached with a unit of about 90 soldiers, mainly Indians and Gurkhas. Although the gathering was unarmed and, it seemed, peaceful, Dyer feared that his small contingent of men would, if things got out of hand, soon be overwhelmed. Deciding attack was the best form of defence, he ordered, without warning, his men to open fire. Bedlam ensued.

With the only entrance blocked, there was no escape from the withering fire that lasted an entire quarter of an hour. People hid behind bodies, others were killed in the circling stampede. Dyer only ordered a stop when he feared his men would run out of ammunition. Without sanctioning any medical aid, Dyer ordered his men out. 379 were left dead, over 1,200 wounded. Dyer did not stop there; in the days that followed Dyer subjected miscreants, as he saw them, to public flogging.

Mistaken concept of duty

At the resultant enquiry, General Dyer was censured for ‘acting out of a mistaken concept of duty’ but survived unpunished. The British press was outraged – not by the lack of punishment but that the British establishment had failed to condone his actions. The Morning Post launched a campaign, raising over £26,000 for the beleaguered general, as they saw him; Rudyard Kipling being one such giver. Reginald Dyer quietly took early retirement and died eight years later humbled perhaps but unrepentant. Indeed, his only regret was that ‘I didn’t have time to do more’.

At the resultant enquiry, General Dyer was censured for ‘acting out of a mistaken concept of duty’ but survived unpunished. The British press was outraged – not by the lack of punishment but that the British establishment had failed to condone his actions. The Morning Post launched a campaign, raising over £26,000 for the beleaguered general, as they saw him; Rudyard Kipling being one such giver. Reginald Dyer quietly took early retirement and died eight years later humbled perhaps but unrepentant. Indeed, his only regret was that ‘I didn’t have time to do more’.

(Pictured, the Jallianwala Bagh Memorial).

Amritsar was systematic of all that was wrong in post-First World War British India. Mahatma Gandhi wrote of the massacre, ‘We do not want to punish Dyer; we have no desire for revenge. We want to change the system that produced Dyer.’

Amritsar confirmed an uncomfortable truism – that ultimately British rule in India was dependent on force.

Gathered together in one collection, 60 of Rupert Colley’s history articles, The Savage Years: Tales From the 20th Century. Also available in paperback and ebook formats.

Gathered together in one collection, 60 of Rupert Colley’s history articles, The Savage Years: Tales From the 20th Century. Also available in paperback and ebook formats.

Sir George Pomeroy Colley was a Victorian general who met his death on 27 February 1881, whilst fighting the Boers in South Africa.

Sir George Pomeroy Colley was a Victorian general who met his death on 27 February 1881, whilst fighting the Boers in South Africa. Much of India, at the time, was governed by the East India Company. The monolithic,

Much of India, at the time, was governed by the East India Company. The monolithic,  The British took refuge on the fort’s ramparts. One soldier escaped, took to his horse and galloped the sixteen miles to the garrison based

The British took refuge on the fort’s ramparts. One soldier escaped, took to his horse and galloped the sixteen miles to the garrison based  In April 1756, the

In April 1756, the

Until 1739, Byng was stationed around the uneventful Mediterranean. Then, perhaps due to his father’s influence, John experienced a rapid rise up the promotional ladder. In 1742, he was given the governorship of the colony of Newfoundland. In 1745 he was appointed Rear Admiral, followed by Vice-Admiral in 1747, all of which he obtained without having seen any military action. His father, George, had been victorious in a number of naval battles, but when his son was finally to be tested it resulted in disaster.

Until 1739, Byng was stationed around the uneventful Mediterranean. Then, perhaps due to his father’s influence, John experienced a rapid rise up the promotional ladder. In 1742, he was given the governorship of the colony of Newfoundland. In 1745 he was appointed Rear Admiral, followed by Vice-Admiral in 1747, all of which he obtained without having seen any military action. His father, George, had been victorious in a number of naval battles, but when his son was finally to be tested it resulted in disaster.