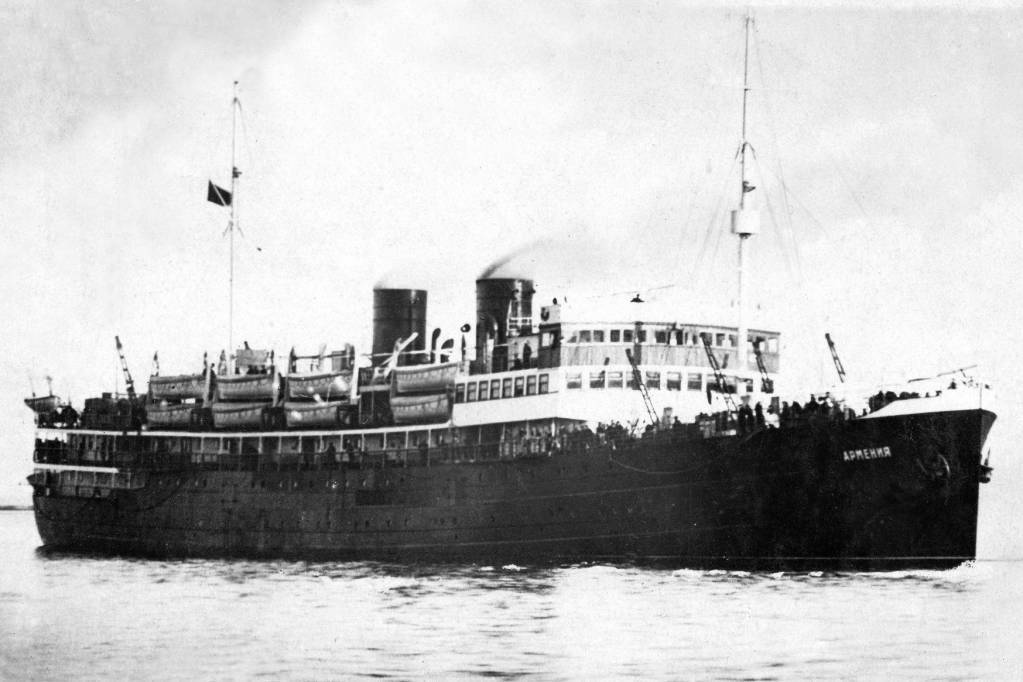

On 7 November 1941, the Soviet hospital ship, the Armenia, was torpedoed and sunk by the Germans. It was one of the worst maritime disasters in history. All but eight of the 7,000 passengers perished on a ship designed for not more than a thousand. A comparatively modest 1,514 died on the Titanic (1912) and 1,198 on the Lusitania (1915) yet the sinking of the Armenia on 7 November 1941 is all but lost to history.

Sunk in the Black Sea, the exact location of the wreck is still a mystery and for years, the question remained – was a hospital ship, identified by a Red Cross, a legitimate target?

Sunk in the Black Sea, the exact location of the wreck is still a mystery and for years, the question remained – was a hospital ship, identified by a Red Cross, a legitimate target?

A stricken city

Designed for 980 passengers and crew, over seven times that number had surged onto the ship in the Crimean port of Yalta that fateful night of 7 November 1941. The reason was blind panic. The Nazi war machine, which had invaded the Soviet Union less than five months before, had overrun the Crimean peninsula and was bearing down on Yalta. People expected the city to fall within a matter of hours. The only possible means of escape for its stricken population was by sea – the roads outside the city having been sealed off by the Germans.

Built in Leningrad in 1928, the double-decker Armenia began its career as a passenger ship. In August 1941, following the outbreak of war, it was pressed into military service as a hospital ship. The day before its sinking, the Armenia had left the port of Sevastopol having taken civilian evacuees and the occupants of several military hospitals. Crammed with up to 5,000 passengers, the ship made for Tuapse, a town on the northeast coast of the Black Sea, about 250 miles east. But the captain, Captain Vladimir Plaushevsky, received orders to pick up extra people from nearby Yalta.

More civilians and wounded soldiers, some severely, crammed onto the ship amid scenes of chaos and utter panic. No register was taken, no names recorded of these additional two thousand passengers. Captain Plaushevsky then received orders to remain in port until escort vessels were at hand to chaperon him out. The delay frustrated the captain, he had to get going; they were cutting it too fine.

Torpedoed

The next morning, seven o’clock, the Armenia finally set sail, escorted by two armed boats and two fighter planes.

The escorts were unable to prevent a German torpedo bomber, a Heinkel He-111, swooping-in low and firing two torpedoes at the ship. It was 11.29 am, the ship was 25 miles into its journey. The first torpedo missed but the second one scored a direct hit, splitting the ship into two. The Armenia sunk within just four minutes. All but eight of the 7,000 passengers died, the survivors being picked up by a patrol boat.

The tragedy lay in the postponement of its departure. If Captain Plaushevsky had not lost those precious hours, the ship may well have arrived at its intended destination.

Lying at a depth of about 480 metres, the location of the Armenia wreck remains unknown despite the efforts of oceanic explorer, Robert Ballard, discoverer of several historical wrecks including the aforementioned Titanic and Lusitania.

A legitimate target?

Was the Armenia a legitimate target? As a hospital ship, it was clearly marked with the Red Cross, both on its sides and, clearly visible to the German pilots, on the deck. But it had a military escort, and it had two of its own anti-aircraft guns, so under the rules of war, it was a perfectly acceptable target.

But this doesn’t detract from the catastrophe of its sinking and today we should remember, if only momentarily, the forgotten tragedy of the Armenia.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

See also the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

The ‘Great War’ was still less than a year old. On 18 February 1915, in response to Great Britain’s blockade of Germany, the Germans announced that it would, in future, be operating a policy of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. In other words, German U-boats would actively seek out and attack enemy shipping within the war zone of British waters. Even ships displaying a neutral flag, they announced, would be at risk – the Germans

The ‘Great War’ was still less than a year old. On 18 February 1915, in response to Great Britain’s blockade of Germany, the Germans announced that it would, in future, be operating a policy of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’. In other words, German U-boats would actively seek out and attack enemy shipping within the war zone of British waters. Even ships displaying a neutral flag, they announced, would be at risk – the Germans  Wealthy passengers boarding the Lusitania, a 32,000-ton luxury Cunard liner, in New York saw an advertisement issued by the US German embassy warning them of the risk:

Wealthy passengers boarding the Lusitania, a 32,000-ton luxury Cunard liner, in New York saw an advertisement issued by the US German embassy warning them of the risk: Built in Germany in 1935 the 800-foot long Zeppelin airship, the Hindenburg, was considered the height of sophisticated travel. It may only have travelled at 80 mph yet it still provided the fastest means of crossing the Atlantic – twice as fast as the speediest ship. It was akin to being on a luxury liner and had already made dozens of journeys across the Atlantic from Germany to Brazil or America and back. Of course, it wasn’t cheap – a one-way ticket across the Atlantic cost about US$400 (about US$7,000 / £4,500 in 2016).

Built in Germany in 1935 the 800-foot long Zeppelin airship, the Hindenburg, was considered the height of sophisticated travel. It may only have travelled at 80 mph yet it still provided the fastest means of crossing the Atlantic – twice as fast as the speediest ship. It was akin to being on a luxury liner and had already made dozens of journeys across the Atlantic from Germany to Brazil or America and back. Of course, it wasn’t cheap – a one-way ticket across the Atlantic cost about US$400 (about US$7,000 / £4,500 in 2016). Exercise Tiger

Exercise Tiger A small fleet of ships and boats arrived on the scene and managed to pluck a few survivors from the icy waters and rescued many of those on the lifeboats. Over a thousand were

A small fleet of ships and boats arrived on the scene and managed to pluck a few survivors from the icy waters and rescued many of those on the lifeboats. Over a thousand were  The ship was named after the assassinated leader of the Swiss Nazi Party (yes, Switzerland in the 1930s had its own Nazi Party), murdered in his own home in February 1936 (Wilhelm Gustloff, pictured).

The ship was named after the assassinated leader of the Swiss Nazi Party (yes, Switzerland in the 1930s had its own Nazi Party), murdered in his own home in February 1936 (Wilhelm Gustloff, pictured).