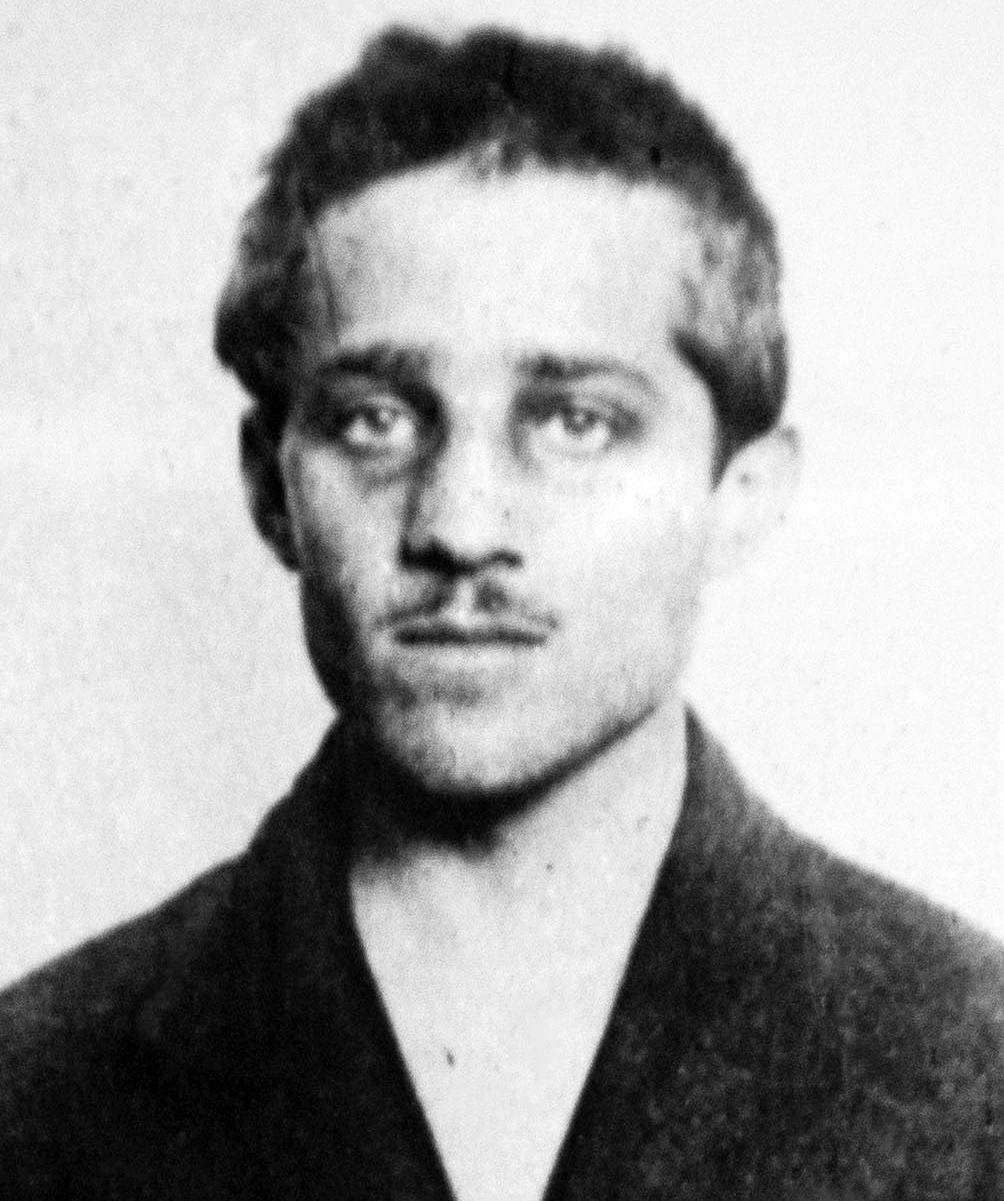

On 15 March 1938, Nikolai Bukharin, one of the leading members of the post-Russian Revolution politburo, was executed.

Born in Moscow on 9 October 1888 to two primary school teachers, the 17-year-old Bukharin joined the workers’ cause during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and, the following year, became a member of the Bolshevik Party. Like many of his radical colleagues, he was arrested at regular intervals to the point that, in 1910, he fled into exile.

Born in Moscow on 9 October 1888 to two primary school teachers, the 17-year-old Bukharin joined the workers’ cause during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and, the following year, became a member of the Bolshevik Party. Like many of his radical colleagues, he was arrested at regular intervals to the point that, in 1910, he fled into exile.

At various times he lived in Vienna, Zurich, London, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Krakow, the latter where he met Bolshevik leader, Vladimir Lenin, and began working for the party newspaper, Pravda, ‘Truth’. In 1916, he moved to New York where he met up with another leading revolutionary, Leon Trotsky.

‘Favourite of the whole party’

Following the February Revolution of 1917 and the overthrow of the tsar, Nicholas II, Bukharin returned to Moscow and was elected to the party’s central committee. Bukharin clashed with Lenin on the latter’s decision to surrender to Germany, thus ending Russia’s involvement in the First World War, believing that the Bolsheviks could transform the conflict into a pan-European communist revolution. Lenin got his way, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsky was duly signed in March 1918.

Bukharin was a thinker and produced several theoretical tracts, works that didn’t always meet with Lenin’s full approval. In Lenin’s Testament, in which he passed judgement on various members of his Central Committee, Lenin wrote that Bukharin was ‘rightly considered the favourite of the whole Party,’ but ‘his theoretical views can be classified as fully Marxist only with the great reserve, for there is something scholastic about him.’ (Lenin’s Testament was particularly damning of Joseph Stalin but, following Lenin’s death on 21 January 1924, was quietly suppressed).

‘Not a man, but a devil’

In 1924, Bukharin was appointed a full member of the Politburo. It was here, during the immediate post-Lenin years, that Bukharin became an unwitting pawn in Stalin’s deadly power games. Bukharin had opposed collectivization and believed agriculture was best served by encouraging the richer peasants, the kulaks, to produce more. In this he was supported by Stalin – but only in order for Stalin to marginalise then remove those he saw as threats, men such as Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev. Kamenev and Zinoviev soon caved in to Stalin. Trotsky, who did not, was exiled, first within the Soviet Union, then to Turkey and ultimately to Mexico where, in August 1940, he was killed by a Stalinist agent. Having defeated his opponents, Stalin then took their ideas and advocated rapid collectivization and the liquidation of the kulaks, criticizing Bukharin for holding opposite views.

Bukharin realised what Stalin was doing: ‘He [Stalin] is an unprincipled intriguer who subordinates everything to his appetite for power. At any given moment he will change his theories in order to get rid of someone.’

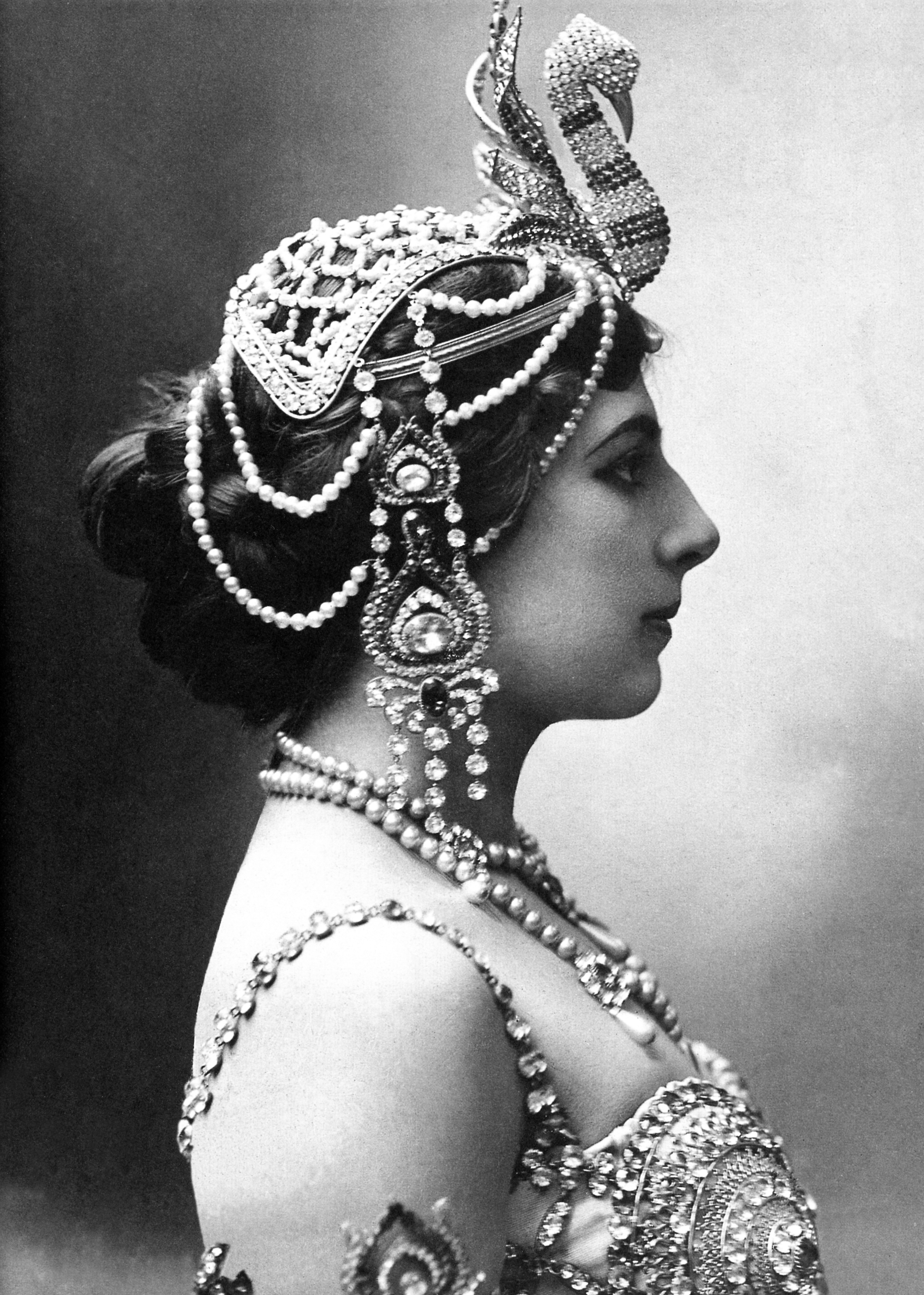

Born 7 August 1876 to a wealthy Dutch family, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married within three months of meeting each other and in 1895 moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children.

Born 7 August 1876 to a wealthy Dutch family, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married within three months of meeting each other and in 1895 moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children. Returning to Paris,

Returning to Paris,  Rupert Colley.

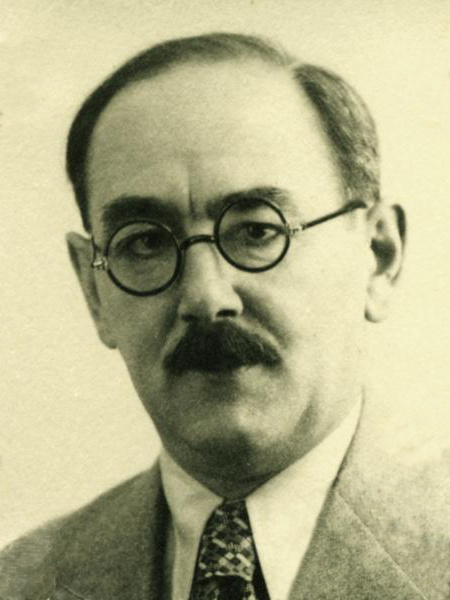

Rupert Colley. Imre Nagy was born 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in southern Hungary. He worked as a locksmith before joining the Austrian-Hungary army during the First World War. In 1915, he was captured and spent much of the war as a prisoner of war in Russia. He escaped and having converted to communism, joined the Red Army and fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Imre Nagy was born 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in southern Hungary. He worked as a locksmith before joining the Austrian-Hungary army during the First World War. In 1915, he was captured and spent much of the war as a prisoner of war in Russia. He escaped and having converted to communism, joined the Red Army and fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Khodynka Tragedy

The Khodynka Tragedy Thomas Highgate was born in Shoreham in Kent on 13 May 1895. In February 1913, aged 17, he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. Within months, Highgate fell foul of the military authorities – in 1913, he

Thomas Highgate was born in Shoreham in Kent on 13 May 1895. In February 1913, aged 17, he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. Within months, Highgate fell foul of the military authorities – in 1913, he  Shoreham

Shoreham Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.