In Budapest, on 16 June 1989, a solemn and symbolic ceremony was held. On this day, almost thirty-three years after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Imre Nagy was re-interred and, 31 years after his execution, honoured with a funeral befitting a man of his stature. Tens of thousands of people lined the routes and crowded into Heroes’ Square, paying their respects to the great man who, more than anyone, had symbolised the hope and the ultimate defeat of the Uprising.

Alongside him, were the coffins of four other leading participants of the Hungarian Revolution, and next to them, a sixth coffin – an empty one to commemorate all the victims of Soviet and communist repression during 1956. Shops and businesses were closed, and schools were given the day off. In the square, flowers and wreaths lay everywhere, Corinthian pillars were decked in black and white, Hungarian flags with the central Soviet emblem removed, and people with bowed heads, united by grief and ingrained memories.

Defeated

Imre Nagy had died exactly thirty-one years previously, on 16 June 1958, less than two years after the communists, with their Soviet masters, had quashed the uprising and re-established one-party rule.

With the uprising defeated, the communists returned, the Hungarian secret police, the AVO, re-emerged in their uniforms and, with their Soviet friends, plucked out leading insurgents for execution and scores more for deportation to Russia. They exhumed the bodies of their fallen colleagues, killed during the revolution, and reburied them with full military honours. By the end of the year, the Iron Curtain was back in place but not before over 200,000 men, women and children had escaped into Austria and the West.

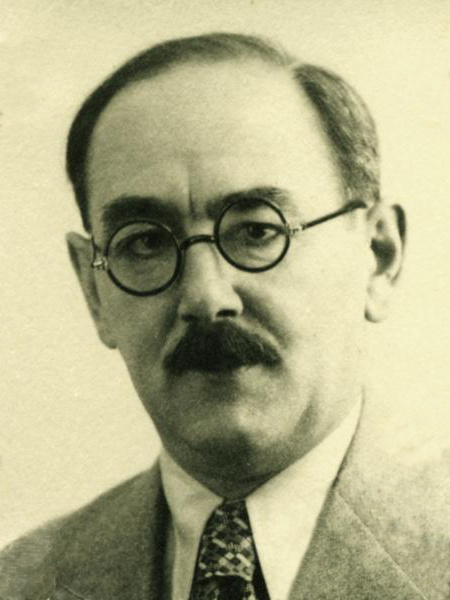

Nagy (pictured) had found asylum in the Yugoslavian embassy but was kidnapped and held by the Hungarian communists for almost two years before they put him on trial that was as secret as it was pointless. On 16 June 1958, they executed him and his ‘fascist counter-revolutionary’ followers and unceremoniously dumped the bodies. Nagy was 62. (Even as late as 1988, on the thirtieth anniversary of Nagy’s death, the police used violence to break up a ceremony in honour of his memory.)

Nagy (pictured) had found asylum in the Yugoslavian embassy but was kidnapped and held by the Hungarian communists for almost two years before they put him on trial that was as secret as it was pointless. On 16 June 1958, they executed him and his ‘fascist counter-revolutionary’ followers and unceremoniously dumped the bodies. Nagy was 62. (Even as late as 1988, on the thirtieth anniversary of Nagy’s death, the police used violence to break up a ceremony in honour of his memory.)

In November 1958, the communists won 99.8% in a single-party election. Everything in Hungary was back to normal.

1989

In the 1989 ceremony, people listened to the eulogies and watched the solemn laying of flowers. They listened to the speeches – words criticising the government and the continued interference of the Soviet Union, and demands for multi-party elections – echoes of 1956; words inconceivable even a few weeks earlier.

The writing was on the wall for Hungary’s communist rulers. Sure enough, on the 33rd anniversary of the start of the revolution, 23 October 1989, the People’s Republic of Hungary was replaced by the Republic of Hungary with a provisional parliamentary president in place. The road to democracy was swift – parliamentary elections were held in Hungary on 24 March 1990, the first free elections to be held in the country since the Second World War. The totalitarian government was finished – Hungary, at last, was free.

Rupert Colley

Rupert Colley

Read more about the revolution in The Hungarian Revolution, 1956, available as ebook and paperback (124 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

Born Joseph Pehm on 29 March 1892 in the Hungarian village of Csehi-Mindszent (the name which, in 1941, Pehm adopted), Mindszenty was ordained a priest in 1915 at the age of 23. He spoke out against Hungary’s short-lived Soviet Republic and was subsequently arrested and imprisoned until its collapse in August 1919.

Born Joseph Pehm on 29 March 1892 in the Hungarian village of Csehi-Mindszent (the name which, in 1941, Pehm adopted), Mindszenty was ordained a priest in 1915 at the age of 23. He spoke out against Hungary’s short-lived Soviet Republic and was subsequently arrested and imprisoned until its collapse in August 1919. On 26 December 1948, Mindszenty was arrested. Stripped naked or dressed as a clown, Mindszenty was tortured, methods that included sleep deprivation, beatings, intense and incessant noise, and forced-fed mind-altering drugs. Finally, after over forty days and nights of continuous torture, the cardinal signed his confession.

On 26 December 1948, Mindszenty was arrested. Stripped naked or dressed as a clown, Mindszenty was tortured, methods that included sleep deprivation, beatings, intense and incessant noise, and forced-fed mind-altering drugs. Finally, after over forty days and nights of continuous torture, the cardinal signed his confession.