On 29 July 1900, the king of Italy, Umberto I, was assassinated. The throne passed to his 30-year-old son, who, as Victor Emmanuel III, would reign until 1946, a period which saw both world wars and the rise and fall of Benito Mussolini’s fascists.

Born in Naples on 11 November 1869, the future king was so short, the German kaiser, Wilhelm II, nicknamed him the dwarf, and, in private, Mussolini called him the ‘little sardine’. He ruled over an Italy that had been in existence as a unified nation only since 1871. Despite unification, Italy was a deeply-fragmented society, steeped in poverty and corruption, and ruled over by a succession of weak coalition governments. But, as a figurehead king, Victor Emmanuel III chose to ignore the affairs of state, preferring instead to focus on his vast collection of coins.

Born in Naples on 11 November 1869, the future king was so short, the German kaiser, Wilhelm II, nicknamed him the dwarf, and, in private, Mussolini called him the ‘little sardine’. He ruled over an Italy that had been in existence as a unified nation only since 1871. Despite unification, Italy was a deeply-fragmented society, steeped in poverty and corruption, and ruled over by a succession of weak coalition governments. But, as a figurehead king, Victor Emmanuel III chose to ignore the affairs of state, preferring instead to focus on his vast collection of coins.

World War One

With the outbreak of war in July 1914, Italy initially adopted a position of neutrality despite having been in alliance, the Triple Alliance, with Germany and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire since 1882. Victor Emmanuel favoured participation in the war, partly as a means of enhancing Italy’s reputation on the international stage. Italy duly entered the war in May 1915, not as allies of Germany and Austria-Hungary, but on the side of the Triple Entente allies – France, Russia and Great Britain.

Mussolini

After 1918, Victor Emmanuel again retired to the sidelines as Italy struggled to cope with the post-war instabilities of demobilization, unemployment and inflation. Socialists, communists, anarchists and the newly-formed fascists fought on the streets and on the farms in a vicious cycle of ever-increasing violence.

In October 1922, with the country on the verge of civil war, the rising star of Italy’s right, Benito Mussolini, led the fascist March on Rome, demanding to form a new government. At first, Victor Emmanuel resisted but then, fearing outright anarchy, bowed to Mussolini’s persistence.

The murder of a leading socialist politician and outspoken critic of the fascists, Giacomo Matteotti, in June 1924 almost caused Mussolini’s downfall. Many suspected Mussolini’s involvement and demanded that the king remove Mussolini from power. Ignoring the national outcry, Victor Emmanuel, more fearful of a socialist takeover, threw his support behind the fascists. Mussolini survived.

For the next 18 years, Victor Emmanuel watched without undue concern as Mussolini ruled the country. Following Italy’s invasions of Ethiopia (1935-36) and Albania (1939), Victor Emmanuel was made emperor of the former and the king of the latter. Having never visited either, he renounced both titles in 1943.

(Pictured, Victor Emmanuel III in 1936).

World War Two

Victor Emmanuel opposed Italy’s entry into the Second World War but was unable to prevent Mussolini from declaring war on France and Great Britain in June 1940. Three years later, on 24 July 1943, with Italy staring defeat in the face, the Italian Fascist Grand Council voted 19 to 8 (with three abstentions) in favour of a resolution to have Mussolini removed from power.

Victor Emmanuel opposed Italy’s entry into the Second World War but was unable to prevent Mussolini from declaring war on France and Great Britain in June 1940. Three years later, on 24 July 1943, with Italy staring defeat in the face, the Italian Fascist Grand Council voted 19 to 8 (with three abstentions) in favour of a resolution to have Mussolini removed from power.

The following day, Mussolini kept his fortnightly meeting with the king, believing that the vote the previous evening was neither constitutional nor binding. He was much mistaken. Almost apologetically, Victor Emmanuel III dismissed the 59-year-old dictator: ‘My dear Duce, it’s no longer any good. Italy has gone to bits… The soldiers don’t want to fight any more… At this moment you are the most hated man in Italy.’

With Mussolini now arrested and held in captivity, Victor Emmanuel signed the armistice with the Allies on 8 September. A month later, having fled to the town of Brindisi, he declared war on Italy’s former allies, Germany.

Princess Mafalda

The king’s daughter, Princess Mafalda, married a prominent Nazi. When her husband fell out with the Nazi regime, he was arrested and Malfalda was interned in Buchenwald concentration camp, where she died on 27 August 1944.

Republic

On 9 May 1946, a year following the end of the war, Victor Emmanuel was forced to abdicate and leave Italy. He moved to Egypt. He named his son as his successor, Umberto II, three weeks ahead of a national referendum to decide on whether Italy should maintain its monarchy. On 2 June, the nation voted 54.3 per cent in favour of becoming a republic. After 85 years, the Kingdom of Italy was at an end.

Victor Emmanuel III died in exile in Egypt on 28 December 1947, aged 78. His son, Umberto II, died in Switzerland in 1983. (Benito Mussolini, meanwhile, was executed by Italian partisans on 28 April 1945).

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more about the war in The Clever Teens Guide to World War Two available as an ebook and 80-page paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

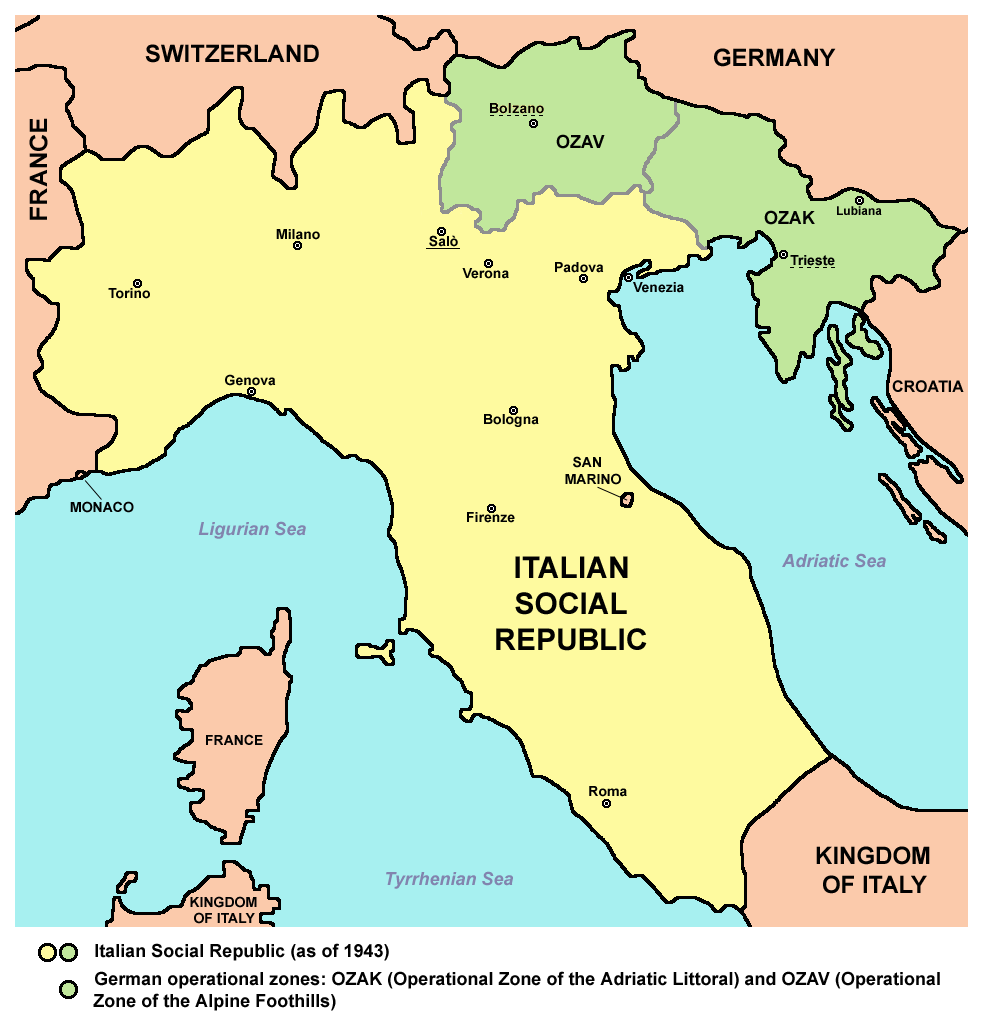

On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook.

On Hitler’s orders, Mussolini was returned to German-occupied northern Italy as the puppet head of the Italian Social Republic, based in the town of Salo on Lake Garda, hence it was often referred to as the Salo Republic. Mussolini wasn’t keen; much preferring the idea of being allowed to slip away into quiet retirement but Hitler had no intention of letting the now reluctant dictator so easily off the hook. While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife,

While head of the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini lived in Salo with his wife,  Mussolini and Rachele Guidi shared the same place of birth – the town of Predappio in the area of Forlì in northern Italy. Guidi had been born on 11 April 1890. She and Mussolini had first met when Mussolini appeared at her school as a stand-in teacher.

Mussolini and Rachele Guidi shared the same place of birth – the town of Predappio in the area of Forlì in northern Italy. Guidi had been born on 11 April 1890. She and Mussolini had first met when Mussolini appeared at her school as a stand-in teacher.  In 1923, Rachele took on a lover of her own – according to Edda in an interview in 1995, shortly before her death and only broadcast in 2001.

In 1923, Rachele took on a lover of her own – according to Edda in an interview in 1995, shortly before her death and only broadcast in 2001.  Forty-three years later, in 2009, in another bizarre postscript, Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini (pictured), model turned politician, discovered that the Italian version of the online auction site, eBay, was

Forty-three years later, in 2009, in another bizarre postscript, Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini (pictured), model turned politician, discovered that the Italian version of the online auction site, eBay, was

Galeazzo Ciano’s father had made a name for himself as an admiral during the First World War. An early supporter of Benito Mussolini’s, he built his fortune through some unethical business deals. Thus, Galeazzo, born 18 March 1903, was brought up in an environment of wealth and luxury, and inherited his father’s love for fascism. Father and son both took part in Mussolini’s 1922 ‘March on Rome’.

Galeazzo Ciano’s father had made a name for himself as an admiral during the First World War. An early supporter of Benito Mussolini’s, he built his fortune through some unethical business deals. Thus, Galeazzo, born 18 March 1903, was brought up in an environment of wealth and luxury, and inherited his father’s love for fascism. Father and son both took part in Mussolini’s 1922 ‘March on Rome’. Mussolini ordered the destruction of the marriage records between him and his first wife, and stopped paying her maintenance, as previously ordered by the courts.

Mussolini ordered the destruction of the marriage records between him and his first wife, and stopped paying her maintenance, as previously ordered by the courts.