On 15 March 1938, Nikolai Bukharin, one of the leading members of the post-Russian Revolution politburo, was executed.

Born in Moscow on 9 October 1888 to two primary school teachers, the 17-year-old Bukharin joined the workers’ cause during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and, the following year, became a member of the Bolshevik Party. Like many of his radical colleagues, he was arrested at regular intervals to the point that, in 1910, he fled into exile.

Born in Moscow on 9 October 1888 to two primary school teachers, the 17-year-old Bukharin joined the workers’ cause during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and, the following year, became a member of the Bolshevik Party. Like many of his radical colleagues, he was arrested at regular intervals to the point that, in 1910, he fled into exile.

At various times he lived in Vienna, Zurich, London, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Krakow, the latter where he met Bolshevik leader, Vladimir Lenin, and began working for the party newspaper, Pravda, ‘Truth’. In 1916, he moved to New York where he met up with another leading revolutionary, Leon Trotsky.

‘Favourite of the whole party’

Following the February Revolution of 1917 and the overthrow of the tsar, Nicholas II, Bukharin returned to Moscow and was elected to the party’s central committee. Bukharin clashed with Lenin on the latter’s decision to surrender to Germany, thus ending Russia’s involvement in the First World War, believing that the Bolsheviks could transform the conflict into a pan-European communist revolution. Lenin got his way, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsky was duly signed in March 1918.

Bukharin was a thinker and produced several theoretical tracts, works that didn’t always meet with Lenin’s full approval. In Lenin’s Testament, in which he passed judgement on various members of his Central Committee, Lenin wrote that Bukharin was ‘rightly considered the favourite of the whole Party,’ but ‘his theoretical views can be classified as fully Marxist only with the great reserve, for there is something scholastic about him.’ (Lenin’s Testament was particularly damning of Joseph Stalin but, following Lenin’s death on 21 January 1924, was quietly suppressed).

‘Not a man, but a devil’

In 1924, Bukharin was appointed a full member of the Politburo. It was here, during the immediate post-Lenin years, that Bukharin became an unwitting pawn in Stalin’s deadly power games. Bukharin had opposed collectivization and believed agriculture was best served by encouraging the richer peasants, the kulaks, to produce more. In this he was supported by Stalin – but only in order for Stalin to marginalise then remove those he saw as threats, men such as Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev. Kamenev and Zinoviev soon caved in to Stalin. Trotsky, who did not, was exiled, first within the Soviet Union, then to Turkey and ultimately to Mexico where, in August 1940, he was killed by a Stalinist agent. Having defeated his opponents, Stalin then took their ideas and advocated rapid collectivization and the liquidation of the kulaks, criticizing Bukharin for holding opposite views.

Bukharin realised what Stalin was doing: ‘He [Stalin] is an unprincipled intriguer who subordinates everything to his appetite for power. At any given moment he will change his theories in order to get rid of someone.’

As a two-year-old in 1903, Nadezhda, or Nadya, Alliluyeva was reputedly saved from drowning by the visiting 25-year-old Stalin. When staying in St Petersburg (later Petrograd), Stalin often lodged with the Alliluyev family. We don’t know for sure but he may have had an affair with Olga Alliluyeva, Nadya’s mother and his future mother-in-law.

As a two-year-old in 1903, Nadezhda, or Nadya, Alliluyeva was reputedly saved from drowning by the visiting 25-year-old Stalin. When staying in St Petersburg (later Petrograd), Stalin often lodged with the Alliluyev family. We don’t know for sure but he may have had an affair with Olga Alliluyeva, Nadya’s mother and his future mother-in-law. The following morning, servants found Nadya dead – she had shot herself with a pistol given to her by her brother, Pavel Alliluyev, as a present from Berlin. (Pavel, who was there that morning and comforted his grieving brother-in-law, would die in suspicious circumstances six years later, aged 44. Indeed, most of the Alliluyev clan would suffer early deaths on the orders of Stalin. His daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, wondered whether Stalin would eventually have had her own mother arrested).

The following morning, servants found Nadya dead – she had shot herself with a pistol given to her by her brother, Pavel Alliluyev, as a present from Berlin. (Pavel, who was there that morning and comforted his grieving brother-in-law, would die in suspicious circumstances six years later, aged 44. Indeed, most of the Alliluyev clan would suffer early deaths on the orders of Stalin. His daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, wondered whether Stalin would eventually have had her own mother arrested). Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. On 23 August 1939, the Nazis and Soviets had signed a non-aggression pact. But both sides knew it was never meant to be more than a postponement of hostilities.

On 23 August 1939, the Nazis and Soviets had signed a non-aggression pact. But both sides knew it was never meant to be more than a postponement of hostilities. Joseph Stalin had died

Joseph Stalin had died At the age of 17, Vasily joined an aviation school, despite only obtaining poor grades. His father’s aides had to ensure his entry. Stalin once described Vasily as a ‘spoilt boy of average abilities, a little savage… and not always truthful,’ and advised his son’s teachers to be stricter with him.

At the age of 17, Vasily joined an aviation school, despite only obtaining poor grades. His father’s aides had to ensure his entry. Stalin once described Vasily as a ‘spoilt boy of average abilities, a little savage… and not always truthful,’ and advised his son’s teachers to be stricter with him. Peace-loving and gentle

Peace-loving and gentle In his latter years, Stalin’s health had deteriorated and towards the end of 1952 he suffered several blackouts and losses of memory. His sense of paranoia had reached absurd proportions. “I’m finished”, he said in his final days, “I don’t even trust myself.”

In his latter years, Stalin’s health had deteriorated and towards the end of 1952 he suffered several blackouts and losses of memory. His sense of paranoia had reached absurd proportions. “I’m finished”, he said in his final days, “I don’t even trust myself.” Peters’ arrival in the US in 1967 (pictured) gave the West a huge propaganda coup – the defection of Stalin’s own daughter was the ultimate proof of how terrible life was behind the Iron Curtain. She had even been prepared to leave behind her two adult children, aged 22 and 17, in the Soviet Union.

Peters’ arrival in the US in 1967 (pictured) gave the West a huge propaganda coup – the defection of Stalin’s own daughter was the ultimate proof of how terrible life was behind the Iron Curtain. She had even been prepared to leave behind her two adult children, aged 22 and 17, in the Soviet Union. Ekaterina Dzhugashvili, known as Keke,

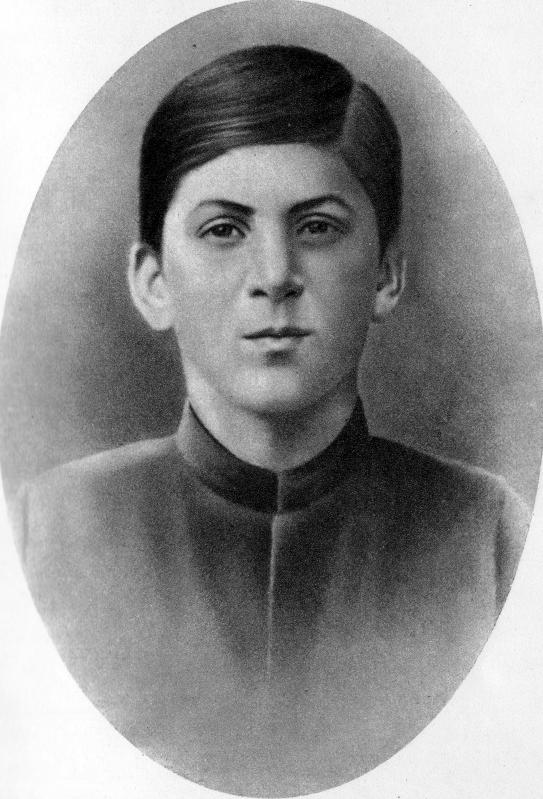

Ekaterina Dzhugashvili, known as Keke,  Joseph Stalin’s father, Vissarion Dzhugashvili, known as Basu, was a shoemaker. An alcoholic, he spent much of his time in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, 50 miles east of Gori) producing shoes for the Russian army. On his drunken and increasingly rare appearances at home, he would beat his wife and son. (Pictured is Stalin, aged 15, in 1894).

Joseph Stalin’s father, Vissarion Dzhugashvili, known as Basu, was a shoemaker. An alcoholic, he spent much of his time in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, 50 miles east of Gori) producing shoes for the Russian army. On his drunken and increasingly rare appearances at home, he would beat his wife and son. (Pictured is Stalin, aged 15, in 1894).