One of the most politically-charged sporting events took place in New York’s Yankee Stadium on 22 June 1938 – a boxing match between the then heavyweight champion of the world, Joe Louis, the ‘Brown Bomber’, and the German, Max Schmeling, the unwilling darling of the Nazi Party.

Born 28 September 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled.

Born 28 September 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled.

The Low Blow Champion

It was an astute move, and the young German was soon a sensation, winning his initial fights on American soil. In 1930, the reigning heavyweight champion, Gene Tunney, retired and Schmeling was pitted against fellow contender, Jack Sharkey. Schmeling won the fight but not in a manner that he would have liked – Sharkey had knocked the German to the floor but was disqualified for throwing a punch below the belt, leaving Schmeling floored and clutching his groin. Thus, with Sharkey disqualified, Schmeling had become World Heavyweight champion by default. The press derided Schmeling’s victory, calling him the ‘Low Blow Champion,’ a nickname that must have hurt. Sharkey’s team, feeling grieved, demanded an immediate re-match.

As heavyweight champion, the only German to have been so, Max Schmeling dispatched a boxer called Young Stribling, before facing Sharkey again in 1932. This time the fight went to 15 rounds, and Sharkey, to the astonishment of neutral onlookers, was given the fight on points, stripping Schmeling of his title. ‘We woz robbed,’ screamed Schmeling’s Jewish trainer, Joe ‘Yussel the Muscle’ Jacobs. The newspapers, and even the mayor of New York, agreed.

Hitler’s Boxer

The following year, Hitler came to power as German Chancellor and the persecution against Jews began in earnest. Max Schmeling’s exploits came to the attention of the Nazi Party and they took the young boxer to their breasts as typical of the Aryan ideal. The Nazis enforced a ban on Jews playing any part in boxing, whether as fighter, trainer, promoter or even fan. Schmeling was told to ditch his Jewish trainer, and to Schmeling’s credit, he refused to do so.

New York, with its large Jewish population, associated Schmeling with the new German regime, not helped that Schmeling’s next fight, in June 1933, was against Max Baer. Although himself not a Jew, Baer’s father had been, which, under Nazi classification, made him a Mischlinge. Bauer came into the ring with the Star of David stitched onto his shorts. The fight was seen as good versus evil, with Schmeling cast as Hitler’s representative in the boxing ring. Baer, much to America’s delight, won.

Schmeling v Louis

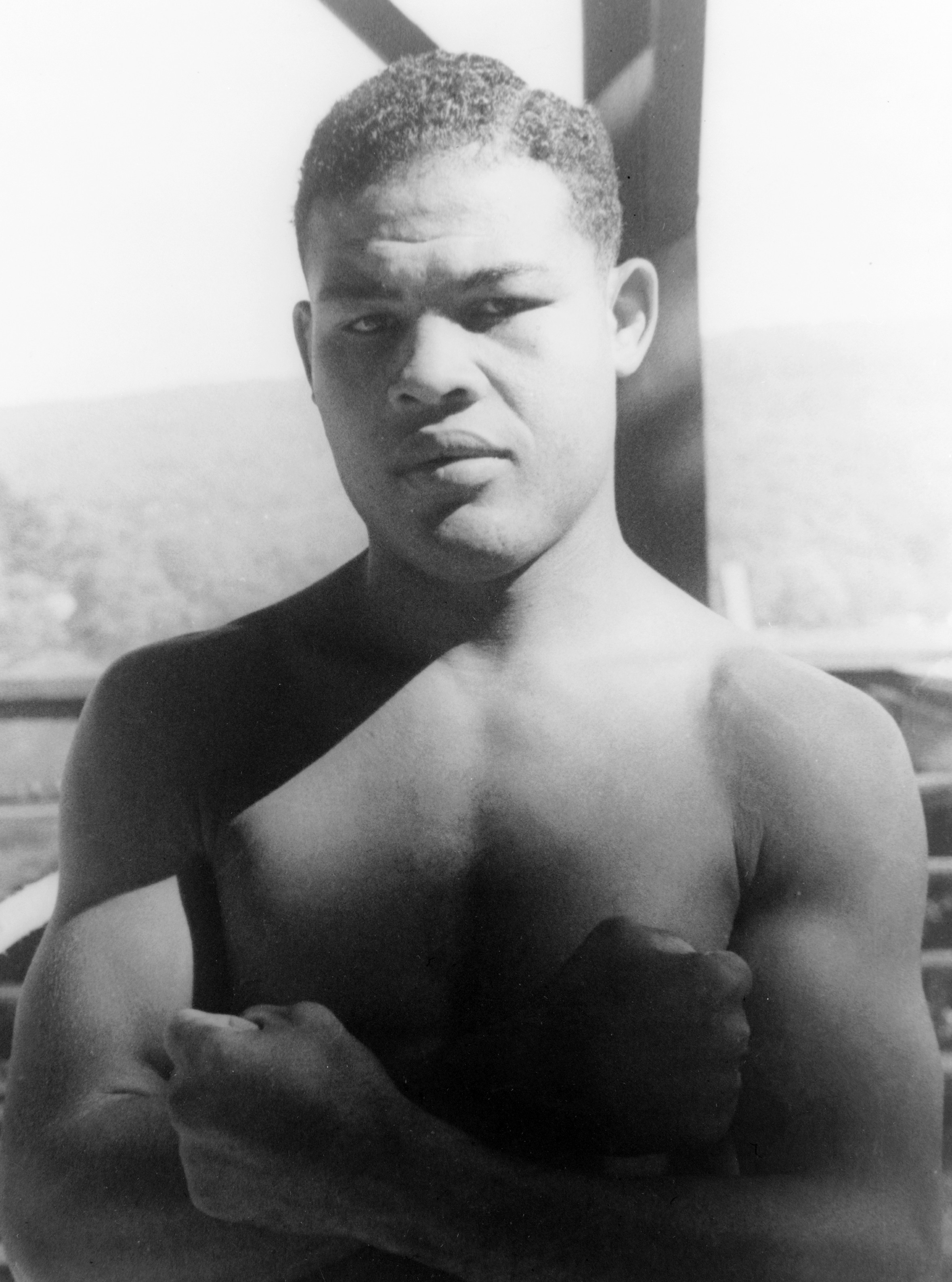

Despite the loss, Schmeling was offered the chance to fight fellow contender, Joe Louis (pictured). Louis was not only the role model of African-Americans but of Americans everywhere as the embodiment of a rags to riches tale, a man living the American dream. Against him, Max Schmeling represented the polar opposite, the land of anti-Semitism and oppression. The Nazis were displeased that Schmeling should deign to fight a Negro but the fight went ahead on 19 June 1936. Schmeling, the underdog, floored Louis twice, knocking him out in the 12th round and winning convincingly. Schmeling was delighted but not overly surprised: ‘I wouldn’t have fought a colored man if I didn’t think I could lick him,’ he told reporters.

Despite the loss, Schmeling was offered the chance to fight fellow contender, Joe Louis (pictured). Louis was not only the role model of African-Americans but of Americans everywhere as the embodiment of a rags to riches tale, a man living the American dream. Against him, Max Schmeling represented the polar opposite, the land of anti-Semitism and oppression. The Nazis were displeased that Schmeling should deign to fight a Negro but the fight went ahead on 19 June 1936. Schmeling, the underdog, floored Louis twice, knocking him out in the 12th round and winning convincingly. Schmeling was delighted but not overly surprised: ‘I wouldn’t have fought a colored man if I didn’t think I could lick him,’ he told reporters.

Schmeling returned to a hero’s welcome in Germany not by ship but by another symbol of German superiority, the Hindenburg airship. Schmeling’s victory was ‘not only sport’, crowed the Nazi weekly journal Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps), ‘it was a question of prestige for our race.’ A new film was released, Schmeling’s Victory: A German Victory, and shown throughout the country. Schmeling was feted as all that was good in Nazi Germany, appearing smiling at the side of Hitler, a fan of boxing, and Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. (Indeed, Schmeling’s wife, Anny, listened to the fight on the radio in Goebbels’s living room). When later quizzed about his meetings with Hitler, Schmeling responded by saying, ‘I once went to dinner with Franklin Roosevelt; that did not make me a Democrat’. But Schmeling did attend Nazi rallies at Nuremberg and supported Nazi charities.

Schmeling returned to New York in May 1937 and had been booked onto the Hindenburg but a last-minute change of plan meant he travelled instead by sea. Thus, by a quirk of fate, Schmeling missed being on the Hindenburg when, arriving in New Jersey, it exploded into flames, claiming the lives of 36.

In New York, Schmeling became a spokesman for Germany, often quizzed about life under the Nazis. For Schmeling, the pressure must have been difficult, especially when the pressure came from Hitler himself: ‘When you go to the United States, you’re going to obviously be interviewed by people who are thinking that very bad things are going on in Germany at this moment. And I hope you’ll be able to tell them that the situation isn’t as bleak as they think it is.’ Hence, in one interview, he said, ‘I have seen no Jews suffer… whatever pain they are undergoing they have brought on themselves by circulating anti-Nazi horror stories in New York and elsewhere.’

Schmeling v Louis: the re-match

Having beaten Joe Louis, Schmeling now wanted a chance of regaining the title from the reigning champion James Braddock, but Braddock’s camp feigned injury, not wanting to be involved with the man they considered a Nazi puppet. Instead, Braddock fought Joe Louis and lost. The Brown Bomber was now the heavyweight champion of the world.

The much-anticipated Louis–Schmeling rematch of 22 June 1938 (pictured) was billed as the ‘fight of the century’, with its politically charged rivalry between the land of the free and the land of Aryan racial purity. Among the 70,000 audience were Gary Cooper and Clark Gable. As he approached the ring, Schmeling was greeted with jeers and pelted with rubbish. The fight lasted all of two minutes and four seconds when Schmeling was knocked out. He spent ten days in hospital recovering from his injuries which included a number of broken ribs. Louis had got his revenge and democracy, it seemed, had triumphed over fascism. But ultimately it was about boxing and that on this particular occasion, the American was better than the German.

The much-anticipated Louis–Schmeling rematch of 22 June 1938 (pictured) was billed as the ‘fight of the century’, with its politically charged rivalry between the land of the free and the land of Aryan racial purity. Among the 70,000 audience were Gary Cooper and Clark Gable. As he approached the ring, Schmeling was greeted with jeers and pelted with rubbish. The fight lasted all of two minutes and four seconds when Schmeling was knocked out. He spent ten days in hospital recovering from his injuries which included a number of broken ribs. Louis had got his revenge and democracy, it seemed, had triumphed over fascism. But ultimately it was about boxing and that on this particular occasion, the American was better than the German.

The German ambassador in America tried to persuade Schmeling to claim foul play against Louis but Schmeling refused. This time, when Schmeling returned to Germany, by humble ship, there was no celebration, no welcome party. Schmeling, now considered a loser, was shunned by the party that had been so keen to embrace him.

Schmeling may have previously appeared as an apologist for the Nazi regime but when faced with its reality, he demonstrated true courage. On the night of 10-11 November 1938, when the Nazis unleashed their battering of Jews and Jewish synagogues and businesses during what became known as Kristallnacht, Schmeling hid two Jewish brothers in his hotel suite for two days, sharing what food he had with them and refusing all visitors, claiming he was ill. Later, Schmeling spirited the boys and family out of Germany. One of them, Henri Lewin, speaking in 1989, paid homage to the boxer, saying that had they been discovered, ‘I would not be here this evening, and neither would Max’.

Private Schmeling

With the outbreak of war in 1939, Schmeling was forcibly drafted into the German army as a paratrooper (pictured) and, as a 36-year-old private, saw action during the Battle of Crete in 1941 where he was wounded. Schmeling believed that the particularly perilous assignment had been the Nazi Party’s revenge on him. No doubt they hoped he would be killed and provide them with a new martyr. When ordered by Goebbels to fabricate tales for the press relating to supposed British barbarity against German prisoners, Schmeling refused. He was promptly court-martialed on the personal orders of the Propaganda Minister.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, Schmeling was forcibly drafted into the German army as a paratrooper (pictured) and, as a 36-year-old private, saw action during the Battle of Crete in 1941 where he was wounded. Schmeling believed that the particularly perilous assignment had been the Nazi Party’s revenge on him. No doubt they hoped he would be killed and provide them with a new martyr. When ordered by Goebbels to fabricate tales for the press relating to supposed British barbarity against German prisoners, Schmeling refused. He was promptly court-martialed on the personal orders of the Propaganda Minister.

Post-war, Schmeling, living in Germany and in need of money, fought five more matches, his first fights since before the war. He fought and lost his final fight in 1948, as a 43-year-old. He started working for the German branch of Cola-Cola, eventually running his own bottling plant and becoming very rich in the process. Meanwhile, in the US, Joe Louis fell on hard times, unable to pay mounting tax debts. Schmeling visited his former boxing rival in the US and helped him along financially. When Louis died in 1981, Schmeling contributed towards the cost of the funeral.

After 54 years of marriage, Schmeling’s wife, Anny, died in 1987. Anny, a former actress of Polish-Czech descent, had starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1929 film, Blackmail, Britain’s first talkie.

Max Schmeling died on 2 February 2005, seven months short of his hundredth birthday.

Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley.

Read more in The Clever Teens’ Guide to Nazi Germany, available as ebook and paperback (80 pages) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.