Stalin wanted Trotsky dead. He’d got rid of Bukharin, Kamenev and Zinoviev and several other old Bolsheviks, but his greatest enemy, Leon Trotsky, was still alive. He’d thoroughly defeated his rival and had chased him out of the country. But still, it wasn’t enough. He didn’t care how long it took as long as Trotsky was liquidated. In August 1940, in faraway Mexico City, an NKVD agent buried an ice pick into the back of Trotsky’s head. Stalin had got his wish.

Born Lev Bronshtein on 7 November 1879 in the village of Yanovka in Ukraine, Leon Trotsky, the son of a prosperous Jewish farmer, became involved in politics from a young age. Arrested in 1898, the 19-year-old Trotsky was exiled to Siberia where he married and had two daughters, both of whom predeceased him. In 1902, he escaped exile using a forged passport bearing the name Trotsky, the name, he later claimed, of a prison guard he had met in Odessa. He made his way to London where, for the first time, he met Vladimir Lenin and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Following the split of the RSDLP, Trotsky’s loyalty floated between the two factions, the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, often repudiating any party ties and holding a stance of non-allegiance. He opposed Lenin on many issues, a stance that was later held against him.

Leon Trotsky, 1915.

Leon Trotsky, 1915.

Following the outbreak of disturbances throughout Russia in 1905, Leon Trotsky arrived in St Petersburg and there joined its council of workers, or ‘Soviet’, becoming its chair until its forced break-up by tsarist troops in December. Trotsky, along with other leaders, was arrested and again sentenced to exile in Siberia. But en route, he escaped and made his way to London before settling in Vienna where he founded and wrote a newspaper for Russia’s workers, Pravda, ‘Truth’, earning the nickname, ‘the Pen’, for his writing. With the outbreak of war in 1914, Trotsky, as a Russian, was forced to leave Austria. He lived in Paris until, expelled for his anti-war writings, he emigrated to Spain and then New York, arriving in January 1917.

Revolution

Trotsky returned to Russia and Petrograd (as St Petersburg was now known) in March 1917 and became, in effect, Lenin’s second-in-command as the Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government and set up a new socialist order. (Trotsky turned 38 the day of the October Revolution.)

In forming the Council of People’s Commissars, Russia’s new government, Lenin initially offered the post of chair, in effect head of state, to Leon Trotsky but Trotsky declined the offer, fearing that having a Jew in charge of a country that was still strongly anti-Semitic could be problematic. Instead, Trotsky was appointed the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs.

Following Russia’s withdrawal from the First World War, Trotsky was appointed War Commissariat, responsible for strengthening and injecting much-needed discipline into the Red Army. His use of former officers of the tsar’s imperial army caused much disquiet within the party, Joseph Stalin being particularly critical, and was another tool later used against him.

The most capable man

Trotsky seemed the natural successor to Lenin. In Lenin’s ‘Testament’, (Lenin’s written assessment of his underlings), he was described as having ‘outstanding ability’ and ‘perhaps the most capable man in the present Central Committee’ but was prone, according to Lenin, of displaying ‘excessive self-assurance’. But Trotsky’s succession was blocked by a troika consisting of Stalin, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev. Trotsky greatly underestimated Stalin, once referring to him as ‘an excellent bit of mediocrity’.

Following Lenin’s death in January 1924, Stalin ensured he was centre place during the funeral arrangements and the funeral itself. Trotsky had been ill and was recovering in a resort in the Caucasus and Stalin’s telegram to him purposefully gave the wrong date for the funeral.

Trotsky was increasingly marginalised by the party to the point in January 1925, he was relieved of his ministry. Kamenev and Zinoviev, two-thirds of the troika, themselves fell out with Stalin and belatedly joined forces with Trotsky. In October 1927, Trotsky was expelled from the Central Committee and the following month from the Communist Party altogether.

Exiled

In January 1928, Trotsky, accompanied by his wife, Natalia Sedova, was exiled to Kazakhstan and finally banished from the Soviet Union altogether in February 1929. After four years in Turkey, two years in France and two in Norway, always heavily under guard, Trotsky settled in Mexico. For a while, he lived in the house of the artist Diego Rivera and, while there, had an affair with Rivera’s wife and fellow artist, Frida Kahlo. Moving into a house in a leafy suburb of Mexico City, Trotsky began writing prolifically – penning, amongst several books and articles, an autobiography, a history of the Russian Revolution and embarking on a biography of Stalin, in which he described Stalin as having ‘played a dismal role during the 1917 revolution’. (The book remained unfinished).

Meanwhile, Moscow hosted the first of the infamous Show Trials in which old Bolsheviks, such as Kamenev and Zinoviev, confessed to various anti-state conspiracies and having acted under the instructions of Trotsky. All were sentenced to death, including Trotsky who was found guilty in absentia.

Leon Trotsky, Natalia Sedova and their son, Lev Sedov, 1928.

Leon Trotsky, Natalia Sedova and their son, Lev Sedov, 1928.

State Museum of Russian Political History.

Trotsky’s two sons from his second marriage both predeceased him: Sergei Sedov was eliminated in 1937 during Stalin’s ‘Great Purge’ while, in February 1938, his brother, Lev, died on the operating table from a supposed acute appendicitis (very likely on the orders of the NKVD).

Assassination

Despite having up to ten guards at a time, in May 1940, Trotsky survived a raid on his house in Mexico, in which his 25-year-old assistant was abducted, tortured and later murdered, and his grandson, Esteban Volkov, was shot in the foot. Trotsky was unharmed but he was less fortunate three months later.

During this time, Trotsky and his wife were befriended by a Canadian called Frank Jacson, who was introduced to them by Trotsky’s secretary who happened to be Jacson’s lover. Jacson was, in fact, Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río, a Spanish communist and agent for Stalin’s NKVD, who had seduced Trotsky’s secretary in order to get close to his intended victim.

On 20 August, about 5.30 pm, Ramon Mercader turned up at Trotsky’s home, asking if Trotsky would read something he’d written. A hot day, Sedova, Trotsky’s wife, asked Mercader, ‘Why are you wearing your hat and topcoat?’ Refusing Sedova’s offer of tea, Mercader followed Trotsky into the study. Sitting down, Trotsky began to read Mercader’s work. Mercader then retrieved the ice pick he’d been hiding within his coat (he had shortened its handle to better conceal it) and struck such a heavy blow to the back of Trotsky’s head that it impacted the brain. Having heard a ‘terrible, soul-shaking cry’, Sedova found her husband ‘leaning against the door…. His face covered with blood, his eyes, without glasses, were sharp blue, his hands were hanging’.

Rushed to hospital, Leon Trotsky died in hospital the following day. It had taken over a decade, but Stalin had got his man.

Sedova hoped that ‘retribution will come to the vile murderers’. Claiming he had acted alone, Ramón Mercader served twenty years in a Mexican prison but never suffered much by way of retribution. Released in 1960, he received a warm welcome from Fidel Castro in Cuba before making his way to the Soviet Union where he was presented with a ‘Hero of the Soviet Union’ award. He died in 1978.

The house in which Trotsky was attacked was later made into a museum, run by Esteban Volkov, the grandson who had been shot in the foot.

Rupert Colley.

Read more Soviet / Russian history in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Russian Revolution (80 pages) available as paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

Read more Soviet / Russian history in The Clever Teens’ Guide to the Russian Revolution (80 pages) available as paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstone’s, Apple Books and other stores.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Thick snow and heavy fog prevented the Americans from employing their airpower and the German advance of 250,000 men forced a dent in the American line (hence battle of the ‘Bulge’). Germans, dressed in American uniforms and driving captured US jeeps, caused confusion and within five days the Germans had surrounded almost 20,000 Americans at the crossroads of Bastogne. Their situation was desperate but when the German commander gave his American equivalent, Major-General Anthony McAuliffe, the chance to surrender, McAuliffe answered with just the one word – ‘Nuts’.

Thick snow and heavy fog prevented the Americans from employing their airpower and the German advance of 250,000 men forced a dent in the American line (hence battle of the ‘Bulge’). Germans, dressed in American uniforms and driving captured US jeeps, caused confusion and within five days the Germans had surrounded almost 20,000 Americans at the crossroads of Bastogne. Their situation was desperate but when the German commander gave his American equivalent, Major-General Anthony McAuliffe, the chance to surrender, McAuliffe answered with just the one word – ‘Nuts’. Initially, the king, George V (pictured), was not enthusiastic about the proposal; not wanting to re-open the healing wound of national grief but was persuaded into the idea by the prime minister, David Lloyd-George.

Initially, the king, George V (pictured), was not enthusiastic about the proposal; not wanting to re-open the healing wound of national grief but was persuaded into the idea by the prime minister, David Lloyd-George. And so in Munich, Hitler planned his overthrow, or putsch, of the Bavarian government followed by a ‘March on Berlin’. The date set, Sunday 11 November 1923, was an auspicious anniversary – five years on from Germany’s defeat in the war, and, on a more practical level, being a Sunday, a day when the armed forces and police were on reserve strength. (Pictured is Hitler and his Munich entourage including, second from right,

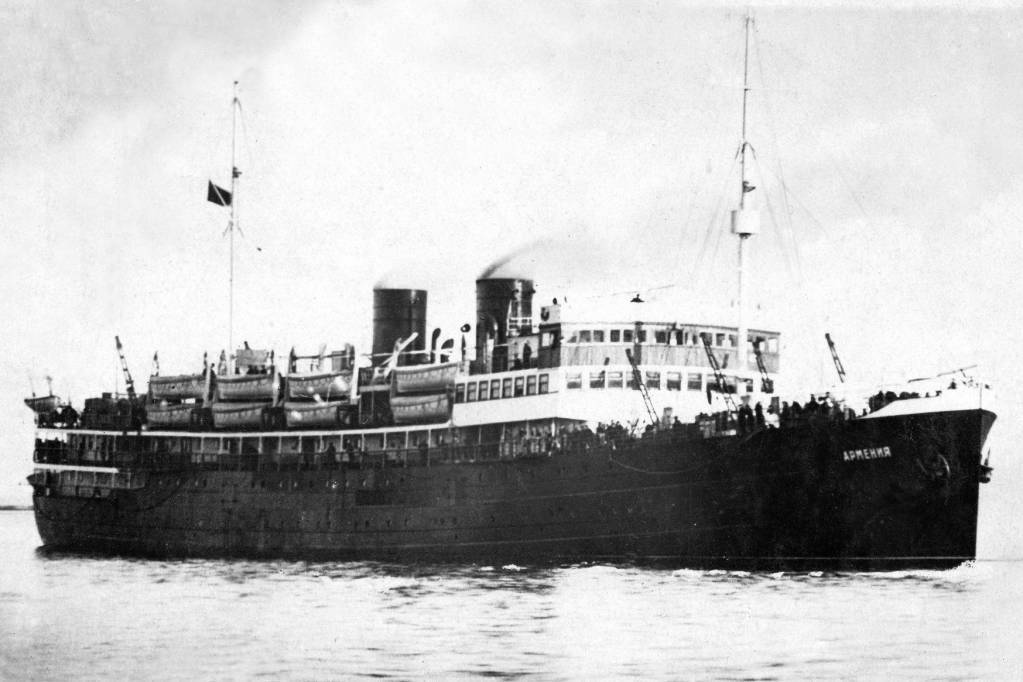

And so in Munich, Hitler planned his overthrow, or putsch, of the Bavarian government followed by a ‘March on Berlin’. The date set, Sunday 11 November 1923, was an auspicious anniversary – five years on from Germany’s defeat in the war, and, on a more practical level, being a Sunday, a day when the armed forces and police were on reserve strength. (Pictured is Hitler and his Munich entourage including, second from right,  Sunk in the Black Sea, the exact location of the wreck is still a mystery and for years, the question remained – was a hospital ship, identified by a Red Cross, a legitimate target?

Sunk in the Black Sea, the exact location of the wreck is still a mystery and for years, the question remained – was a hospital ship, identified by a Red Cross, a legitimate target? Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. Born 15 November 1891, Erwin Rommel was, as Churchill suggests, respected as a master tactician, the supreme strategist who, in 1940, helped

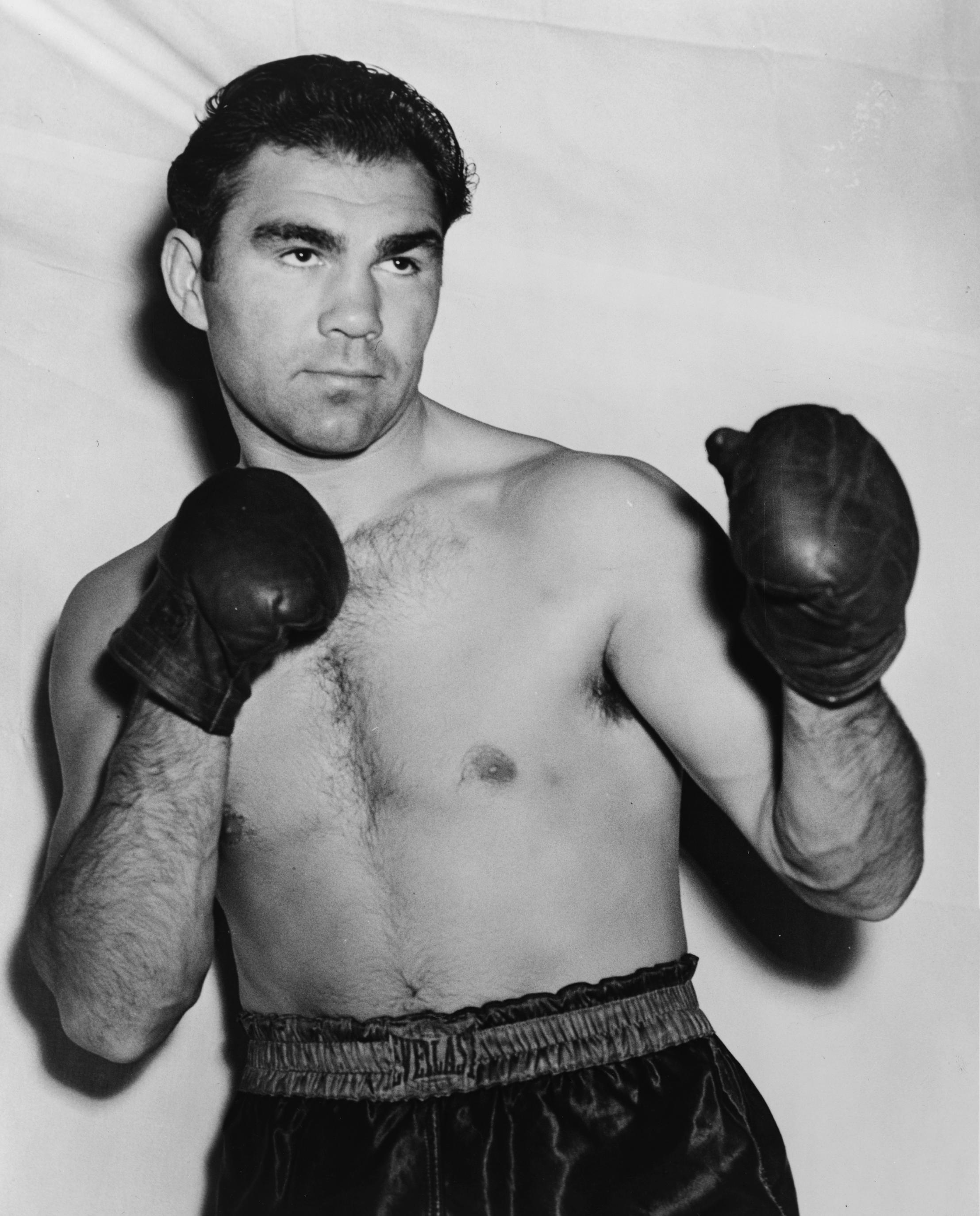

Born 15 November 1891, Erwin Rommel was, as Churchill suggests, respected as a master tactician, the supreme strategist who, in 1940, helped  Born 28 September 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled.

Born 28 September 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled. A staunch republican and troublemaker, like his father, Georges Clemenceau was once imprisoned for 73 days (some sources state 77 days) by Napoleon III’s government for publishing a republican newspaper and trying to incite demonstrations against the monarchy. In 1865, fearing another arrest, and possible incarceration on Devil’s Island, Clemenceau fled to the US, arriving towards the end of the American Civil War. He lived first in New York, where he worked as a journalist, and then in Connecticut where he became a teacher in a private girls’ school. Clemenceau married one of his American students, Mary Plummer, and together they had three children before divorcing seven years later. (Of his son, Clemenceau, known for his wit, said, ‘If he had not become a Communist at 22, I would have disowned him. If he is still a Communist at 30, I will do it then.’)

A staunch republican and troublemaker, like his father, Georges Clemenceau was once imprisoned for 73 days (some sources state 77 days) by Napoleon III’s government for publishing a republican newspaper and trying to incite demonstrations against the monarchy. In 1865, fearing another arrest, and possible incarceration on Devil’s Island, Clemenceau fled to the US, arriving towards the end of the American Civil War. He lived first in New York, where he worked as a journalist, and then in Connecticut where he became a teacher in a private girls’ school. Clemenceau married one of his American students, Mary Plummer, and together they had three children before divorcing seven years later. (Of his son, Clemenceau, known for his wit, said, ‘If he had not become a Communist at 22, I would have disowned him. If he is still a Communist at 30, I will do it then.’) As a two-year-old in 1903, Nadezhda, or Nadya, Alliluyeva was reputedly saved from drowning by the visiting 25-year-old Stalin. When staying in St Petersburg (later Petrograd), Stalin often lodged with the Alliluyev family. We don’t know for sure but he may have had an affair with Olga Alliluyeva, Nadya’s mother and his future mother-in-law.

As a two-year-old in 1903, Nadezhda, or Nadya, Alliluyeva was reputedly saved from drowning by the visiting 25-year-old Stalin. When staying in St Petersburg (later Petrograd), Stalin often lodged with the Alliluyev family. We don’t know for sure but he may have had an affair with Olga Alliluyeva, Nadya’s mother and his future mother-in-law. The following morning, servants found Nadya dead – she had shot herself with a pistol given to her by her brother, Pavel Alliluyev, as a present from Berlin. (Pavel, who was there that morning and comforted his grieving brother-in-law, would die in suspicious circumstances six years later, aged 44. Indeed, most of the Alliluyev clan would suffer early deaths on the orders of Stalin. His daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, wondered whether Stalin would eventually have had her own mother arrested).

The following morning, servants found Nadya dead – she had shot herself with a pistol given to her by her brother, Pavel Alliluyev, as a present from Berlin. (Pavel, who was there that morning and comforted his grieving brother-in-law, would die in suspicious circumstances six years later, aged 44. Indeed, most of the Alliluyev clan would suffer early deaths on the orders of Stalin. His daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, wondered whether Stalin would eventually have had her own mother arrested). Rupert Colley.

Rupert Colley. Leon Trotsky, 1915.

Leon Trotsky, 1915. Leon Trotsky, Natalia Sedova and their son, Lev Sedov, 1928.

Leon Trotsky, Natalia Sedova and their son, Lev Sedov, 1928.