During the early 1920s, Adolf Hitler became convinced that the way to power lay in revolution. Revolution had brought power to the Bolsheviks in Russia and had almost done the same for the Communists in Germany during the chaos of the immediate post-First World War period. Hitler watched, with fascination and admiration, as Mussolini took over power in Italy following his March on Rome in October 1922.

And so in Munich, Hitler planned his overthrow, or putsch, of the Bavarian government followed by a ‘March on Berlin’. The date set, Sunday 11 November 1923, was an auspicious anniversary – five years on from Germany’s defeat in the war, and, on a more practical level, being a Sunday, a day when the armed forces and police were on reserve strength. (Pictured is Hitler and his Munich entourage including, second from right, Ernst Röhm).

And so in Munich, Hitler planned his overthrow, or putsch, of the Bavarian government followed by a ‘March on Berlin’. The date set, Sunday 11 November 1923, was an auspicious anniversary – five years on from Germany’s defeat in the war, and, on a more practical level, being a Sunday, a day when the armed forces and police were on reserve strength. (Pictured is Hitler and his Munich entourage including, second from right, Ernst Röhm).

A Beer Hall in Munich

But when Hitler learned about, and indeed was invited to, a public meeting in a Munich beer hall on the evening of 8 November, hosted by government figures such as Gustav Ritter von Kahr, leader of the Bavarian Government, and the Bavarian chiefs of police and army, the opportunity was too perfect to pass by. At his side were Hermann Goring and Rudolf Hess.

The National Revolution Has Begun

As the meeting progressed, Hitler’s armed corps of bodyguards, the SA, silently surrounded the building. With the bulk of his men in place, others noisily barged into the beer hall, interrupting proceedings and shouting ‘Heil Hitler’.

A machine gun was hauled in and the audience, fearing a massacre, cowered and hid beneath their chairs. Hitler took his cue and, brandishing a revolver, charged to the front, leaped onto a chair and, firing two shots into the ceiling, declared that he was the new leader of the German government and that the ‘National revolution (had) begun’. He then forced the three men on the stage, Kahr and his chiefs, into a side room, apologised to them for the inconvenience, and promised them prestigious jobs in his new Germany.

Returning to the stage, Hitler delivered a rousing speech, winning over his audience who applauded ecstatically. They applauded with equal enthusiasm when Hitler’s famous co-conspirator, General Erich von Ludendorff, made his appearance. Ludendorff, as the joint head of Germany’s military during the First World War, was well-known and respected, and Hitler hoped that with Ludendorff as his mascot it would win him support. It seemed to be working.

Ludendorff’s task was to persuade Kahr and his chiefs to support the revolution and join the March on Berlin. After some reluctance, the three men eventually acquiesced.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the city, the SA, led by Hitler’s confidant, Ernst Rohm, was successfully securing vital strong points. Hitler, his speech done and his audience converted, left the beer hall to check on progress.

The Gullible Old General

Continue reading →

Like this:

Like Loading...

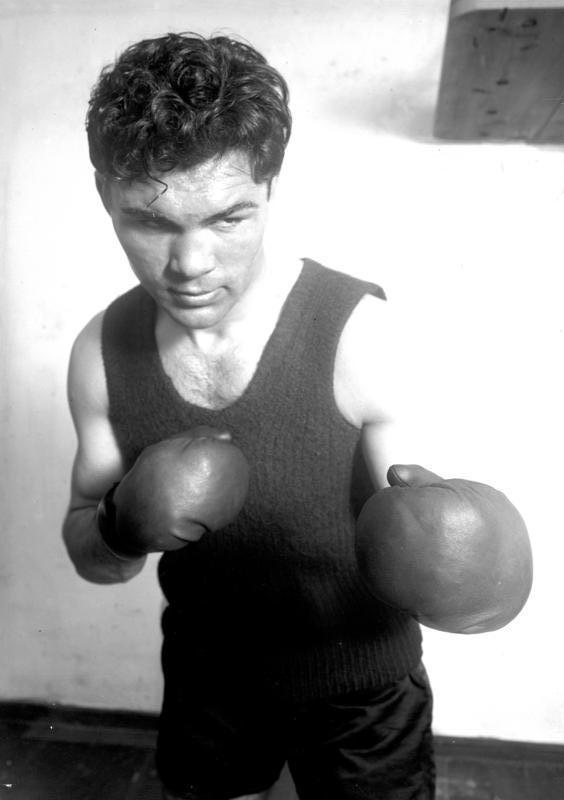

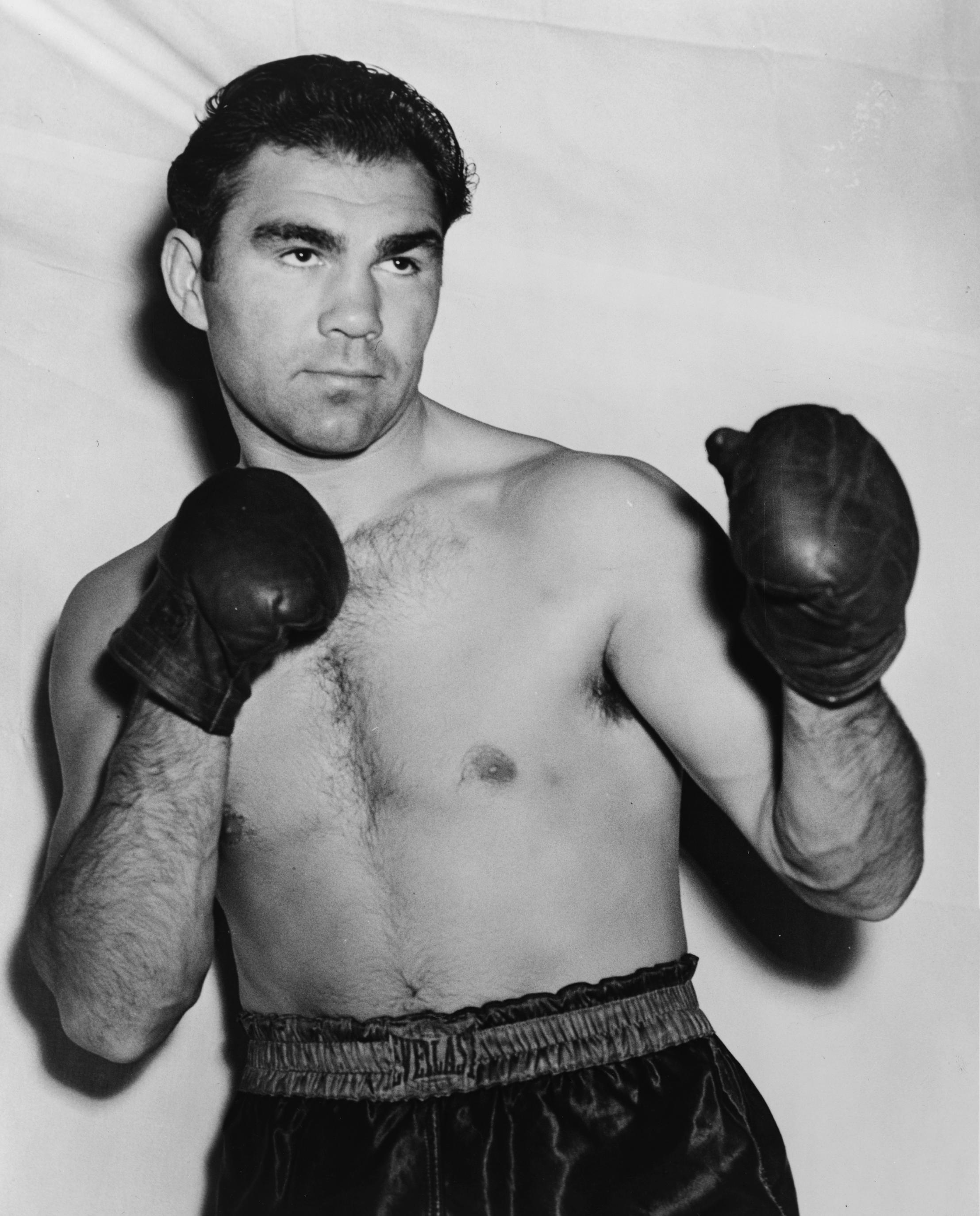

Born in 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled.

Born in 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled. And so in Munich, Hitler planned his overthrow, or putsch, of the Bavarian government followed by a ‘March on Berlin’. The date set, Sunday 11 November 1923, was an auspicious anniversary – five years on from Germany’s defeat in the war, and, on a more practical level, being a Sunday, a day when the armed forces and police were on reserve strength. (Pictured is Hitler and his Munich entourage including, second from right,

And so in Munich, Hitler planned his overthrow, or putsch, of the Bavarian government followed by a ‘March on Berlin’. The date set, Sunday 11 November 1923, was an auspicious anniversary – five years on from Germany’s defeat in the war, and, on a more practical level, being a Sunday, a day when the armed forces and police were on reserve strength. (Pictured is Hitler and his Munich entourage including, second from right,  Born 15 November 1891, Erwin Rommel was, as Churchill suggests, respected as a master tactician, the supreme strategist who, in 1940, helped

Born 15 November 1891, Erwin Rommel was, as Churchill suggests, respected as a master tactician, the supreme strategist who, in 1940, helped  Born 28 September 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled.

Born 28 September 1905, Max Schmeling had advanced through the boxing ranks within Germany and Europe and even impressed Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion, in a friendly fight during the champion’s tour of Europe. But to be a true star of the boxing world, one had to conquer the US. And it was to America, in 1928, the 23–year-old Schmeling travelled. In 1907, Hitler moved to Vienna while August Kubizek remained in Linz to work as an apprentice

In 1907, Hitler moved to Vienna while August Kubizek remained in Linz to work as an apprentice

A fervent supporter of Hitler, 36-year-old Count Claus von Stauffenberg had fought bravely during the Second World War for the Fuhrer. Fighting in Tunisia in 1943, Stauffenberg was badly wounded, losing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers of his left. Once recovered, Stauffenberg was transferred to the Eastern Front where he witnessed the atrocities firsthand which made him question his loyalty. As it became increasingly apparent that Germany would not win the war, Stauffenberg lost faith in Hitler and the Nazi cause.

A fervent supporter of Hitler, 36-year-old Count Claus von Stauffenberg had fought bravely during the Second World War for the Fuhrer. Fighting in Tunisia in 1943, Stauffenberg was badly wounded, losing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers of his left. Once recovered, Stauffenberg was transferred to the Eastern Front where he witnessed the atrocities firsthand which made him question his loyalty. As it became increasingly apparent that Germany would not win the war, Stauffenberg lost faith in Hitler and the Nazi cause. The earlier chapters concern Hitler’s upbringing, his formative years in Linz, Vienna, and Munich, his desire to be an

The earlier chapters concern Hitler’s upbringing, his formative years in Linz, Vienna, and Munich, his desire to be an